<1>Caroline Herschel’s work was inimitable. Michael Hoskin, the late historian of astronomy and longtime Herschel biographer whose work did more than anyone’s to cement the family’s legacy in the 20th- and 21st-centuries' history of science, reported that he was unable to find a single error in his review of her voluminous output (Hoskin 2001, 144). And she did produce in volume. Between 1783 and 1802, in what Hoskin describes as “one of the greatest astronomical campaigns in history,” Caroline and her brother William co-discovered 2,510 new celestial objects, roughly 25 times the number discovered by their near contemporary, Charles Messier (Ibid., 91); Caroline’s two-decade-long work of reducing this mass of data to a usable format formed the basis of the New General Catalogue.

<2>These discoveries and the ways in which they were made inaugurated modern cosmology by shifting astronomy’s focus to large-scale structures in deep space and time. Above all, the siblings’ precision, planning, careful capture, retention, and processing of data, and factory-like division and coordination of labor made astronomy businesslike, an inheritance they passed down to John Herschel, founder of the Royal Astronomical Society and William’s son/Caroline’s nephew, who himself understood the deep sky surveys they inaugurated as “great masses of scientific capital laid up as a permanent and accumulating fund, the interest of which will go on increasing with the progress of years” (J. F. W. Herschel 1831, 219). But if the Herschel siblings’ legacy was to industrialize astronomy, much of their work involved learning how to achieve this revolutionary re-organizational feat with a staff of two in their residence-cum-observatory at Slough; and in this Romantic-era cottage-industrial context, Caroline inhabited the essential roles of line worker, middle manager, and CFO.

<3>This essay contributes to the substantial body of scholarship into Caroline Herschel by attending to this businesslike dimension of her life and work as a professional astronomer. In doing so, it complements the attention usefully paid to her work as an observer (she discovered eight comets and, by Wolfgang Steinicke’s tabulation, seven deep sky objects [Steinicke 2024]). Her work as computer and operations manager for the Herschel observatory is with good reason often seen as a disappointment of her earlier professional ambitions in the more glamorous domains of stage performance and scientific discovery, and as an exploitative squandering of her talents, but a closer investigation of the more mundane and invisibilized labor that occupied the majority of her working life is necessary to understand her impact on the history of astronomy, the nature of her exploitation, and what we have emphasized and de-emphasized in our definition of discovery.

Cottage-Industrial Labor Relations

<4>The Herschels were an educated, Hanoverian family of musicians. William, born in 1738, served in the Hanoverian Guard’s band with their father, but deserted at the outbreak of war in 1757 and with stoic determination built a successful musical career in England, eventually settling with his brother Alexander in Bath, where he established himself as a much-sought-after tutor. Caroline, born in 1750, who remained in Hanover, had an equally hard time but fewer opportunities to strive beyond it. In 1772, at the age of twenty-two, her brother returned to Hanover and requested of their mother that Caroline should accompany him to England as an assistant in his growing trade—their mother only consented to part with her daughter/maid on the condition that William pay her out for the loss of this domestic help (Herschel 1876, 26).

<5>In England, Caroline was instantly employed in the kind of task that would occupy her ceaselessly. “On the second morning, on meeting my brother at breakfast, he began immediately to give me a lesson in English and arithmetic, and showed me the way of booking and keeping accounts of cash received and laid out” (Herschel 1876, 32). Caroline, attempting the little English she has only just learned to “parrot” back on the short trip from Germany, has learned what her core occupation would be: neither music nor astronomy, so much as to serve as her brother’s capable factotum.

<6>The mode of instruction she describes is equally informative as to their working relationship. Caroline is to learn to perform William’s basic tasks first by following example, but as quickly as possible to function independently, without needing further direction:

One of the principal things required was to market, and about six weeks after coming to England I was sent alone among fishwomen, butchers, basket-women, &c., and I brought home whatever in my fright I could pick up .... My brother Alex. who was now returned from his summer engagement, used to watch me at a distance, unknown to me, till he saw me safe on my way home. (Herschel 1876, 33)

<7>Caroline is made to hit the ground running, whether or not she stumbles along the way; her brother Alex’s chaperoning is a comfort, but only after the fact, as she learns to operate as though without a safety net. This independence served her well in life as she came to interface regularly with royal households in England and Germany, and world-renowned scientists who traveled from afar to visit their observatory, but beneath this more liberatory dimension, there is an undercurrent of exploitation to her role in the Herschel household. Caroline is being trained up in all of William’s interests so as to be able to execute his work for him, especially as those interests evolve and change.

<8>Household management provides a common but stark example of this mixture of being entrusted with responsibility and yet subjected to subordination. As Caroline effectively took on the role of lady of this bachelor house, she necessarily had to manage not only their expenditures at market but the people employed by the household as well, and in her few nods to these relations we can gain a sense of how she internalized the household’s needs. Immediately following her description of going to market, she describes their domestic employee at Bath rather unfavorably: “But all attempts to introduce any order in our little household proved vain, owing to the servant my brother then had — a hot-headed old Welshwoman. All the articles, tea-things, &c., which I was to take in charge, were almost all destroyed: knives eaten up by rust, heaters of the tea-urn found in the ash-hole, &c” (Herschel 1876, 33).

<9>Reflecting with displeasure a half century later on an older domestic servant’s poor reception of a person who was clearly a threat to her employment, we can see Caroline identifying not with the woman who had previously been, as Caroline at the time of writing was, a woman advanced in her years and worried about no longer being seen as useful, but rather with the orderly management of a household in which she was always, uncertainly, both employer and employee.

<10>It is a particularly poignant example because Caroline, roughly fifteen years after her difficult encounter with this older woman, was to find herself turfed out of her own domestic role in the household. By 1786, she had been an accomplished professional singer and a trained astronomer with several discoveries under her belt, all the while managing her brother’s household; but with William’s marriage in 1788, she was suddenly to relinquish her status as lady of the house. She took up lodging outside of the main house, and later on, with one of their employees and his wife as a boarder down the way. In her memoir, she is rather pointed about the wedding constituting a definitive end to an era in their partnership:

The catalogue of the second thousand new nebulae wanted but a few numbers in March to being complete. … The 8th of that month being fixed on for my brother's marriage, it may easily be supposed that I must have been fully employed (besides minding the heavens) to prepare everything as well as I could against the time I was to give up the place of a housekeeper, which was the 8th of May, 1788. (Herschel 1876, 77)

<11>Her fixation on this date is personal, but it directly implicates the history of astronomy. The siblings’ monumental deep sky survey, which spanned from 1783–1802, truly only lasted five years, effectively ending on the date of William’s marriage. Their observational runs, which they called “sweeps” due to the particular way that they oscillated the telescope, and the bands of the celestial sphere this covered as a result, dropped precipitously. From 1783–1788, they conducted an annual average of 187.5 sweeps; but from 1789 onwards, they averaged only 15 and never rose above 67 (Fig. 1).

<12>The Herschels’ domestic matters, in short, cannot be separated from the history of astronomy, because this was not an ordinary household. Populated by three bachelor siblings who worked day and night at intellectual pursuits that required ever-growing flows of capital investment, it is hard to find a contemporary analogue, but one appears from a surprising quarter: the literary world, in the household of Dorothy and William Wordsworth. Dorothy quit a teaching job to throw in with her brother, and the two did not exactly retire to the countryside to write poetry so much as pioneer a new understanding of nature within poetic thought. William would come to be seen as having his head in the clouds (and wandering lonely as one), but this airy disposition required a tranquil domestic grounding. Dorothy, establishing their household at Grasmere, was kinder-in-word but more meticulously disciplinary-in-deed to her housekeeper than Caroline was/would be:

Our servant is an old woman 60 years of age whom we took partly out of charity and partly for convenience. She was very ignorant, very foolish, and very difficult to teach so that I once almost despaired of her, but the goodness of her dispositions and the great convenience we knew we should find if my perseverance was at last successful induced me to go on. She has now learned to do everything for us mechanically, except those parts of cooking in which the hands are employed … I help to iron at the great washes about once in 5 weeks, and she washes towels stockings, waistcoats petticoats etc once a week such as do not require much ironing. This she does so quietly in a place apart from the house and we know so little about it as makes it very comfortable. … She is much attached to us and honest and good as ever was a human being. (Wordsworth 41-2)

<13>Dorothy’s micro-management of this housekeeper is focused less on ensuring they are fed and cleanly clothed than on ensuring the work is done invisibly (“mechanically” and “quietly in a place apart”), in order to enable the literati to pursue their composition as though this background labor was not taking place. But Dorothy’s dual role, like Caroline’s, must be emphasized; good help is hard to find and if you want a job done right, you have to do it yourself. In order for the household to conduct its work in peace, Dorothy had to meticulously train her by example, playing both employer and employee. William, of course, had only the one role: becoming a famous poet.

<14>The managerial aspects of Caroline’s life were rather more industrial and could bring out the worst in her. She recounts the 1786 construction of their crown-funded, forty-foot telescope, which was essentially non-functional, ruinously expensive, and yet destined for fame in its iconic status as the face of the Astronomical Society’s gold medal. This construction required hiring out tradespeople and support staff and turning the house into not just a workshop, but an industrial site with an overflow of people and equipment:

I cannot leave this subject without regretting, even twenty years after, that so much labour and expense should have been thrown away on a swarm of pilfering work-people, both men and women, with which Slough, I believe, was particularly infested. For at last everything that could be carried away was gone, and nothing but rubbish left. Even tables for the use of workrooms vanished: one in particular I remember, the drawer of which was filled was slips of experiments made on the rays of light and heat, was lost out of the room in which the women had been ironing. This could not but produce the greatest disorder and inconvenience in the library and in the room into which the apparatus for observing had been moved, when the observatory was wanted for some other purpose; they were at last so encumbered by stores and tools of all sorts that no room for a desk or an Atlas remained. It required my utmost exertion to rescue the manuscripts in hand from destruction by falling into unhallowed hands or being devoured by mice. (Herschel 1876, 59)

<15>Caroline seems to have identified with the role of manager, or at least not at all with the washerwomen, carpenters, other tradespeople, vermin, or excessive mechanical equipment, all of whom equally represent household chaos. But insofar as we are put off by this manager’s vitriolic complaint that laborers only make her job harder, we also need to recall her tenuous situation as both employer and employee, with the maddening task of organizing a momentous scientific achievement with a staff of two, and to sweep the other chaotic inputs under the rug.

<16>Following Mary-Ellen Bellanca’s description of the Wordsworths, we might call this particular, gendered model of household organization “cottage industrial” (Bellanca, 121). The dynamic we see in both households is one calculated to produce genius while making it look natural. This meant that Caroline’s principal task in the household was, as we saw above, to take over the management and if necessary the doing of any task that was deemed beneath William’s notice. And if William Wordsworth’s head was in the clouds, William Herschel’s was in deep space, leaving quite a lot beneath his notice.

Data-Driven Observation

<17>Writing to her nephew John in 1823, Caroline describes her scientific reputation in terms that have cast a long shadow on our understanding of her contributions to the Herschel legacy: “I did nothing for my brother but what a well-trained puppy dog would have done, that is to say, I did what he commanded me” (Herschel 1876, 167). This widely-quoted self-characterization captures the two modes in which her exploitation is expressed in the scholarship. First, her work is portrayed as subordinate to William’s. She diligently crunches the numbers while his vision brilliantly penetrates the depths of space. Second, her agency is frustrated by his command over her life. At his command, she becomes a singer, then quits her fledgling singing career to become an astronomer, and finally, once an astronomer, trades the telescope for a pen and becomes William’s amanuensis rather than the full-time observer at just the moment she begins finding real success in this domain as well.

<18>The passage from Caroline’s letter to John from which this quote comes, however, is as rich with quiet pride and irony as it is with regrets and lamentations:

I have mentioned it over and over again that I was so unlucky as to lose the paper on my journey you entrusted to my care for Prof. Gauss. If you have another copy to spare … I shall be introduced to him shortly, when he comes through Hanover again, where he passed through about a fortnight ago on a journey of observation, tending to establish some new discovery of his own, of which we are soon to know more. The theodolite has something to do with it; so much I snapt up in a company of learned ladies who, within these last two months, have taken me into their circle. But I am imitating Robinson Crusoe, who kept up his consequence by keeping out of sight as much as possible when he acted the governor, and when they want to know anything of me, I say I cannot tell!.... I did nothing for my brother but what a well-trained puppy dog would have done, that is to say, I did what he commanded me. (Herschel 1876, 166-7)

<19>This famous woman is writing to her famous nephew about a document that he has asked her to personally deliver to the famous German polymath, Gauss. She is reporting that she knows his general itinerary because of the social circles she moves in. And most importantly, she describes how she navigates that society – as a world-renowned woman astronomer sitting in a room of Hanoverian learned ladies (whom she has left-handedly compared to Crusoe’s island of animal subjects), she must demur and not outshine them too brightly. As Caroline sharply observes in a subsequent letter to John, “I know too well how dangerous it is for women to draw too much notice on themselves” (Herschel 1876, 231).

<20>In the previous section, we identified dynamics in the Herschels’ cottage-industrial household that encouraged Caroline to take on work that William saw as beneath him, and to make that work invisible. We also suggested that this dynamic helped to produce the public image of William Herschel as a genius. “Invisibilization” is a sociological term for the process by which under-valued labor in society is hidden from those who are exempted from it and who often feel shame upon seeing it. Traditionally applied to manual labor (and laborers), it has come to find purchase in analyses of the distribution of credit amongst knowledge workers. For instance, in academia, we tend to find lower-value tasks falling disproportionately to women and people of color, with a cumulative effect of recognized achievement / prestige being unequally distributed towards white men (SSFNRIG 2018).

<21>Invisibilization therefore provides a good framework for understanding the link between the subordination of Caroline’s labor and the production of William’s reputation as a genius. However, her situation is a complex one. On the one hand, she has to hide and devalue her own labor. As she says to John regarding the speech given on the occasion of her 1828 award of a gold medal from the Royal Astronomical Society, “Whoever says too much of me says too little of your father! and only can cause me uneasiness” (Herschel 1876, 232). Caroline appears to subscribe to the idea that William’s prestige requires her subordination, and therefore to worry that any elevation on her part will drag down his memory. Such a felt need to maintain a subordinate position would explain why she presented her invaluable work as that which a “trained puppy-dog would do.” But on the other hand, this work of devaluing and subordination was not always straightforward. As we saw above in our discussion of domestic labor, the invisibilization of labor in this cottage-industrial setting is a second full-time job. The two astronomers were experimenting with new methods rapidly through 1783, and so it was not always clear what work was going to prove out as high-value and what as low-value. In these moments, subordination takes on an active role and becomes legible. We will be focusing on two such moments in their 1783-1802 deep sky survey with the 20-foot telescope: their shifts to vertical sweeping and to large-scale data processing.

Vertical Sweeping

<22>We might first consider the way in which the Herschels moved their telescope during their observational runs, which they called “sweeps” for reasons that will become clear. Their campaign (as well as John’s later campaign that completed their survey) hinged upon a particular technique of vertical oscillation. Caroline was the first to practice it and to explain the reasoning behind adopting the method, and she insisted on her priority in this apparently minor, technical innovation, one which resulted in radically scaling their observatory’s output in a way that turned them into the natural historians of the sky. However, because it is simply a different way of moving the telescope, this innovation is easily subsumed under the larger project with all its other work, and so was adopted without fanfare and never mentioned again, despite being the origins of their campaign.

<23>Caroline achieved her fame as an observer for her discovery of comets. Encouraged to begin searching for these in 1782, she used a refracting telescope designed to “sweep” along the ecliptic, looking for new nebulous objects, and then, if one was found, to observe it on subsequent nights in order to detect any motion against the backdrop of the fixed stars. Instead, she found nebulae. On a sweep in February, she found two nebulae which were not contained in their (outdated) version of Messier’s catalogue, one of which did indeed prove out as a discovery over which she had priority; she would go on to discover another in March (Steinicke 2024). William, surprised at this quick tempo of discoveries, began turning his own attention to nebulae; “[w]ithin a few days he was paying Caroline the sincerest form of flattery: imitation” (Hoskin 2005, 376).

<24>But on July 8, 1783, she began using a new, Newtonian-reflecting sweeper that her brother had constructed for her. This telescope allowed her to sweep horizontally as readily as before, but its mechanics optimized it for vertical sweeps. Hoskin explains:

Her little refractor rotated about its axis during her horizontal sweeps, inconveniently taking the eyepiece (and Caroline) with it. But in a Newtonian, the eyepiece is to one side of the upper end, and if the tube is designed to pivot in a vertical plane about this upper end, the eyepiece will of course rotate as the tube moves from the horizontal to the vertical but will otherwise be motionless. (Hoskin 2005, 378)

<25>Caroline not only enjoyed the use of this new telescope, but immediately adopted the technique of vertical oscillation as her standard. In her notes for July 8, she writes, “Note my sweeps will be perpendicular for the future; all those before have been horizontal” (RAS MS, C.1/1.1, 11). These two minor changes, of a search for nebulous deep sky objects and a vertical sweeping motion, transformed their work.

<26>Continuously sweeping vertically over a tighter band, Caroline would be able to record numerous stars in that band, while the sky took over the horizontal motion for her by sweeping past as the planet turned. And by pointing the telescope due south, Caroline had begun to use the telescope as a transit instrument. The observer would be able to easily determine the declination of any object that passed through their field of view simply by recording the time that it crossed the meridian. William describes it thus on December 3:

I now began to sweep in a different manner, which I find much more convenient, & also better …. I place the telescope in or near the meridian; then raise and depress it alternately, so as to return in a different tract of stars. By experience I find that my perpendicular sweep may be about 1½ degree about the equator. (RAS MS, W.4/1.5, 467)

<27>With William’s adoption, this method became their standard practice from 1784 onward, was fundamental to the campaign that produced their thousands of deep sky discoveries, and provided William the raw data to mine and hypothesize about the structure and mechanics of the universe. It also divided their labor and removed Caroline from the telescope. But not only was she the first to practice this method, there are indications that she wanted to establish priority. On September 25, following her July 8 adoption of vertical sweeping and well before William’s December entry, she wrote a uniquely defensive entry in her observation notebook:

I began to sweep at α Aquarii when it was a little past the meridian; and swept as far as ω Pisci um & Π Andromeda. without changing my situation. NB. I have adopted this method ever since the 8th of July. finding by experience that the time of sweeping in the meridian answerd to the meridian passage of the stars. (RAS MS, C.1/1.1, 23)

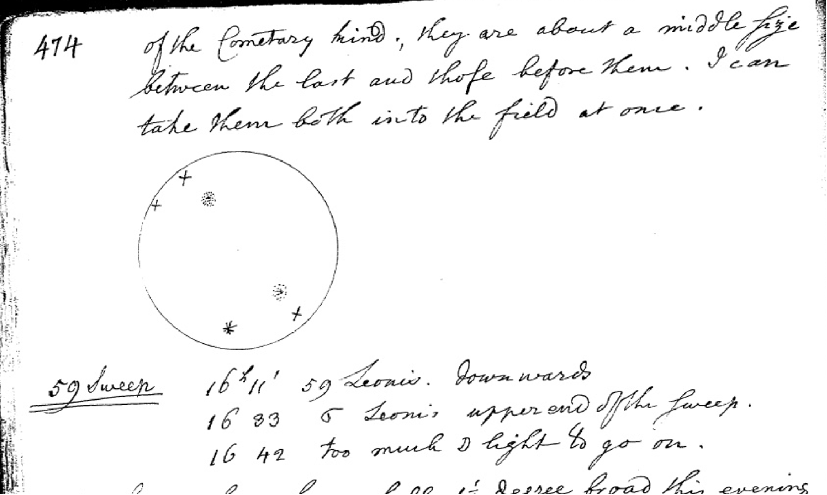

<28>Caroline’s entry describing the method by way of an example run, noting its origin date, and clearly justifying its utility, is clearly superior to William’s as an account of their adoption of this method. That she provided it in this detail three months prior to William’s entry on the subject indicates, at the least, that she fully understood its significance, even if her motives are ultimately unknowable.

<29>In late 1783, their 20-foot reflector came online, and William quickly adopted the vertical sweeping technique in his use of it. This combination of new instrumentation and a new observational technique led inexorably to a more radical division of their labor. Pointed due South, this telescope would cover a tight horizontal band of the sky for as long as the observer, high in the scaffolding, would look through at the magnified sky moving past, while someone else oscillated the apparatus vertically. But as William soon discovered, because the observer would be looking so deep into space with the telescope in constant, oscillating motion, they would not be able to easily keep track of where, exactly, they were looking, or what was and was not a new object; adrift in deep space, the observer would need waypoints in order to know what they were seeing. This configuration produced a constant stream of visual data that required constant checking against existing datasets, reorganized for this purpose.

<30>Their observatory, then, was reorganized on the following system: the twenty-foot telescope rested on an A-frame mount; William perched on an elevated platform or by the telescope’s aperture, and a workman, Mr. Sprat, stood at the base of the frame to control the telescope’s vertical oscillations. Caroline remained indoors, seated in a lit room, surrounded by instrumentation, reference materials, and her recording book. Her desk faced a window that opened towards the telescope, through which she shouted information to William as he needed it, and in turn received his observations as he made them.

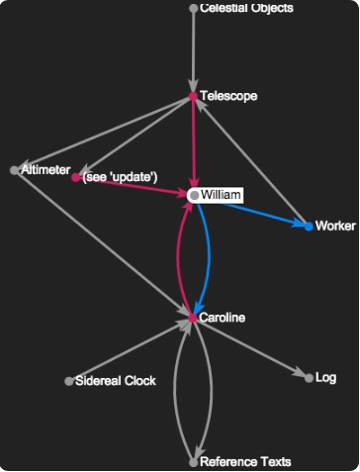

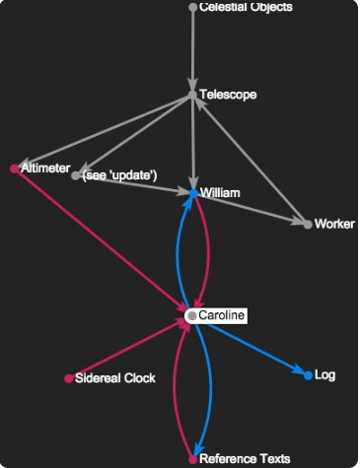

<31>The above representation allows us to see how information flowed between the different actors in the observatory (Fig. 2). William was closest to the stars and the privileged instrument (the telescope), but Caroline was connected to everything else, including the data that William needed to conduct his observations and have them recorded. Put differently, she is the most central node in the graph.

<32>The significance of these changes to their effectiveness cannot be overstated. They could now systematically cover the northern sky in short horizontal bands, slowly but methodically capturing any deep sky object that crossed the meridian within that bandwidth. In the below visualization, produced by the author and a then-graduate student researcher in 2021, we can begin to see how this transformed the night sky from a celestial sphere populated by the heavenly bodies of constellations named for mythical figures, into a large-but-finite territory to be systematically surveyed.

<33>We have seen, then, how the deep sky surveys of 1783-1802 that cemented their legacy as the inaugurators of modern cosmology relied upon three key changes to their observatory’s internal organization, and that Caroline was pivotal to all three: the search for nebulae, the adoption of an exclusively vertical sweeping method, and the division of labor into parallel tasks of observation and data recording.

<34>Invisibilization is at work here, but in a halting, confused manner. With respect to the search for nebulae, Caroline had been tasked with nebulous objects in the sky (comets), but her quick discoveries of deep sky nebulous objects indicated the enormous potential in this alternative line of inquiry. Her prior work, of uncertain value, turned out to be the most valuable work they could be doing. With respect to the vertical sweeping, this apparently minor change in their technique transformed the night sky into surveyor’s tracts to be mined for their invaluable data. Caroline’s innovation here, which she insisted on in her notes, is taken up by William with a casualness that belies its significance. Her work, in short, is devalued, but not before it radically transforms their entire approach. Finally, with respect to the reorganization of their division of labor from the siblings observing in parallel to her serving as data recorder, we see her relegated to a lower-status task as she moves away from the role of observer. However, this last change bears further explanation, as it opens onto their transition into a data-driven organization.

Keeping the Books

<35>As Hoskin observed of Caroline’s Newtonian sweeper, it allowed the observer to sit motionless when it was oscillated vertically. This configuration of an immobile observer staying in sync with the slow, apparent motion of the sky was key to astronomy’s establishment as the paradigmatic precision science of the nineteenth century. As Simon Schaffer observes, the clock-like motion of the sky allowed astronomers to measure their own, individual accuracy against the regularity of the phenomena they studied, turning the astronomers into yet another precision instrument in the observatory (Schaffer, 1988). What is more, they calculated these “personal equations” by dividing labor precisely as the Herschels had: with an observer gazing fixedly through a telescope, and a recorder staring fixedly at a clock.

<36>What is particularly striking about William’s role in their reorganized observatory is how mechanical it became. With his eye fixed to the telescope, his task became one of quickly identifying potential nebulae as the sky and telescope slowly but inexorably moved in unison to provide him with a stream of observational data.(1) However, as noted above, the data he needed to check his observations against were contained in charts and tables that it would be inefficient for him to monitor, especially if he were to use candlelight to the detriment of his night vision. That crucial data therefore had to be managed by Caroline, amidst her books and instruments indoors. While observation was of course fundamental to the enterprise, the value of their survey relied on an aggregate of observations, putting data management and processing at the center of their observatory’s work, and Caroline was central to the pre-processing, real-time processing, and post-processing of this data. As in the examples provided earlier of Caroline’s innovations, we see a confused move towards invisibilization. A gendered division of labor separates higher-value observation from lower-value computation, but in doing so renders observation mechanical. This mechanical observational practice cranks out discoveries, but in doing so puts the work of pre-processing and post-processing this voluminous data at the center of the observatory’s operations.

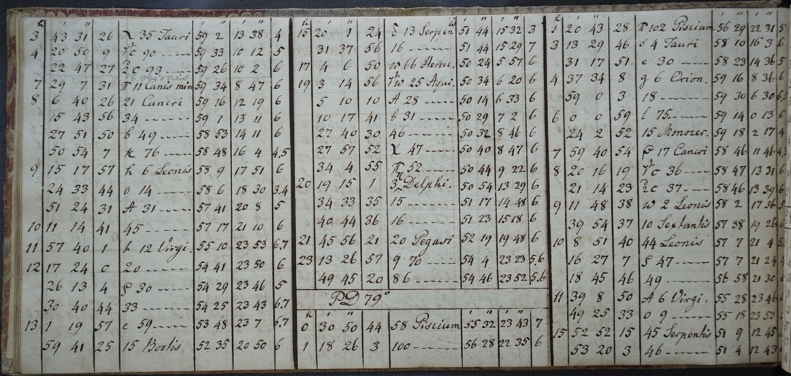

<37>Before a sweep could begin, they had to know what stars they were looking for. Caroline provided the data for this. Recall that they were oscillating the telescope vertically in order to answer the horizontal movement of the stars – they had a schedule to keep in order not to miss patches of sky and potential discoveries. In order to be able to maximize their observational data collection, Caroline had to anticipate that night’s needs in terms of data that would have to be ready-to-hand. To aid this, she reorganized the British Catalogue of fixed stars, accompanied with the Herschels’ own corrections, according to horizontal “zones” of polar declination that would better answer the needs of their sweeps, which also followed horizontal bands in the sky, as shown below. During the sweep, Caroline recorded William’s descriptions in real time. As Hoskin puts it, “Speed and accuracy, not understanding, were what he asked of her” (Hoskin 2003, 69). But she delivered rather more than what was asked of her.

<38>And each morning after a session, Caroline created clean copies of the observations made. These notebooks are invaluable in reconstructing the Herschels’ nightly work as a chronologically organized sequence of numbered sweeps. They describe where the siblings started sweeping and how far they carried on, whether they broke off for any period of time and if so when they resumed, and frequently provide illustrations of their discoveries. These observation notebooks are data-rich but of course they are raw data and in themselves very difficult to use for reference. Any auditor, including the Herschels themselves, would have a great deal of difficulty finding William’s observation for a given object, and would be entirely stymied in any kind of aggregate survey.

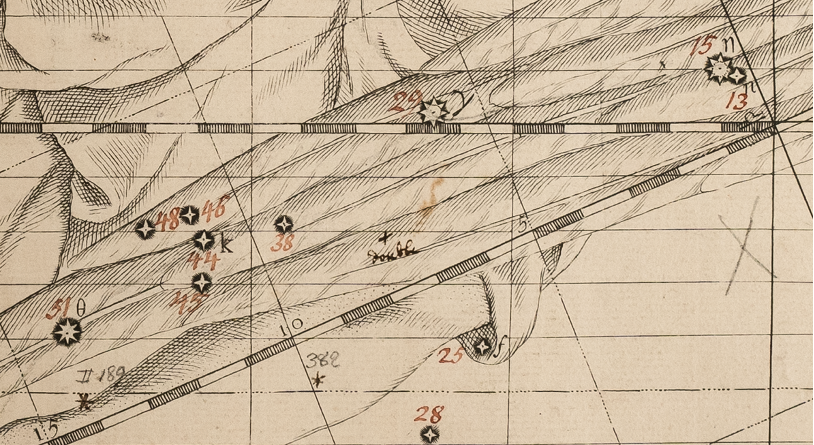

<39>Neither would a visual atlas be able to reasonably accommodate the volume of their discoveries. Consider the Herschels’ occasional practice of recording their discoveries in their copy of Flamsteed’s Atlas Coelestis, whose large-format visual presentation of the constellations was an excellent reference for orienting an observer or to aid them in choosing a known star to examine in detail, but were ill-suited to the sort of systematic, deep sky survey the Herschels had undertaken.

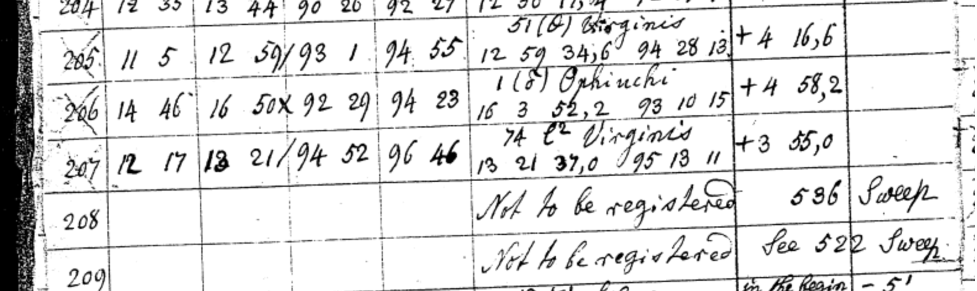

<40>For instance, in the above detail to the plate centered on Virgo, they leave two marks in pen near Gamma Virginis, for their 207th sweep’s April 25, 1784 discoveries of NGC 4731 (numbered “382”) and NGC 4981 (numbered “II 189”) and, apparently later, in Caroline’s hand with pencil, annotating them with her numbering system. But their coverage in this visual medium is far from complete; they discovered several other deep sky objects in this immediate area which are not marked in their copy of the Atlas (Steinicke, 2024). Indeed, it would have been highly inefficient to do so, and much less accurate than recording the precise location in right ascension and declination, which is to say, in a more numerically-oriented organization of their data for faster lookup.

<41>In 1825, after her retirement to Hanover, Caroline undertook precisely this task of reorganizing their sweep data, in order to aid John’s planned resumption of the siblings’ sweeps, to complete the survey of the northern and southern skies. Working systematically through their long records of sweeps, she extracted, reorganized, and transformed these raw observations into a format that would allow for ready comparison across the whole dataset. This involved “reducing” the data from these sweeps into a consolidated and normalized format and adjusting each star’s position according to its date of observation to its proper position for the year 1800. Her guide in this work was a tabulation of their sweeps’ parameters: where they began, where they left off, and the reference stars used for those positions. This manuscript, C 3/2.1, “Sweeps calculated for 1800,” enabled her to check off each observation run in order.

<42>This is a different way of seeing the sky than that we encounter in Flamsteed’s Atlas. Organized not by constellation but by tight horizontal bands in the sky, we see in granular detail their coverage of the northern sky (this data enabled our visualization of their coverage shown in figure 3 above). The result of Caroline’s work on these reductions would be a clean catalogue of all the deep sky objects discovered by the siblings between 1783 and 1802 in the course of their 1,112 sweeps, arranged in a format ideal for John’s use in his completion of their work.

<43>Indeed, the value of this polar declination-oriented catalogue of deep sky objects was apparent enough that it contributed significantly to her award of RAS’s gold medal in 1828. In James South’s speech on the occasion of the award, he notes these reductions as the immediate cause of their award, for “presenting in one view the results of all Sir William Herschel’s observations on those bodies, thus bringing to a close half a century spent in astronomical labour” (Herschel 1876, 224). South’s speech entrenches a gendered understanding of intellectual labor, with William characterized as a genius and Caroline as dutiful, but interestingly comes close to putting them on an equal footing: “Indeed, in looking at the joint labours of these extraordinary personages, we scarcely know whether most to admire the intellectual power of the brother, or the unconquerable industry of the sister” (ibid.). Uncertainly subordinate and equal, Caroline’s data-oriented work is celebrated in a way that the labors of her inheritors, the women computers in nineteenth- and twentieth-century science, never again would be, at least not in an uncontested manner.

<44>It would be inaccurate, however, to say that the recognition of Caroline’s computational work went uncontested. Caroline appears to have been initially pleased, if somewhat overwhelmed, by the award of the gold medal. The medal was sent to her on May 5, and on June 3, she responded with modest thanks.

And I must once more repeat my thanks to you (and perhaps to Mr. South) for thinking so well of me as to exert yourselves for having the great and undeserved honour of a medal bestowed on me … Here I was interrupted, and all along of the medal; for my friends are all coming to congratulate me, and leave me no time to think of what to say of myself; but I will soon write again …. (Herschel 1876, 228)

<45>John, however, had just prior to her June 3 letter sent a follow-up letter dated May 28, in which he insisted that he opposed the award: “Before this reaches you, you will have got it [the medal]. Pray let me be well understood on one point. It was none of my doings. I resisted strenuously. Indeed, being in the situation I actually hold, I could do no otherwise. The society have done well. I think they might have done better, but my voice was neither asked nor listened to” (Herschel 1876, 227).

<46>Caroline’s biographer (John’s daughter) attributes his reservations to “modesty,” but Caroline sensed something more. Her initial pleasure turned to chagrin when, at some point between June and late August, she finally read John’s follow-up letter: “What you tell me in the short note dated May 24th, which accompanied the three copies of my Index, concerning the medal, has completely put me out of humour with the same; for to say the truth, I felt from the first more shocked than gratified by that singular distinction …” (Herschel 1876, 231). She then, in passages quoted earlier in this article, discussed the importance of modesty for women (“how dangerous it is for women to draw too much notice on themselves”) and a concern that her elevation would diminish her brother’s reputation (“Whoever says too much of mesays too little of your father!”). Modesty, here, seems not to have been a virtue that John exercised in opposing his aunt’s recognition; and if we can call her subsequent reaction modesty, it was modesty induced by shame and fear. Again, it was not enough for Caroline to do excellent work, and to do it quietly – she also had to erase this work so that others might benefit from it unencumbered.

<47>This is not just about Caroline’s or William’s legacy. The stakes of subordinating work like Caroline’s, and more generally, of reserving the right to value different kinds of work differently, implicated the future of astronomy, which would be professional, industrial and, in a word, business-like. W. J. Ashworth, in his own study of John Herschel, Francis Baily, and Charles Babbage, refers to them as “‘business astronomers’” who “emphasized an astronomy that encompassed and demonstrated their values of vigilance, calculation, precision, and accurate accounting” (Ashworth 1994, 410). Schaffer concurs, recounting a dispute at the Paramatta observatory during which a disgruntled assistant absconded with the records and John Herschel, among others, intervened to ensure that he did not receive credit for the work. “[A]stronomical work was fantasized as capitalist enterprise, with prudent ledgers, patient accountants, disciplined observers, well-oiled machinery, and precision values as sources of profit” (Schaffer 2010, 124). In a capitalist enterprise, the profits accumulate upwards. In order for this industrial capitalist scientific endeavor to succeed in producing geniuses and paradigm-shifting discoveries, managers must invisibilize the work of their subordinates. John saw this clearly, as did Caroline, though with her dual role in the enterprise, it was her own labor that she was forced to devalue—but not, in this case, before she had won her country’s highest recognition for achievement in her field.

Bills and Receipts

<48>In the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin resides a sizeable collection of Herschel materials, contained in which is a remarkable memorandum book whose first page bears a prefatory note:

Dear Nephew, This is the fragment of a Book which was too bulky for the portfolio, in which I was collecting such papers as I wished might not fall into any other but your own hands. They contain chiefly answers of your Father to the inquiries I used to make when at breakfast, before we separated, each for our dayly tasks &c. &c. (M0672 36.25, frontmatter)

<49>Based on its contents, Caroline sent this to John no earlier than 1830; she had been organizing her papers and sending these to the family since 1828. Filled with equations, facts, names of famous astronomers, and miscellaneous notes, it is an artifact that could only be personal to people such as Caroline, William, and John, who lived their lives in joint scientific pursuits; but given such individuals, it provides a pinhole view into the shared domestic life of the siblings.

<50>William’s table manners toward his sister could have used improvement. Above, we saw him drilling her in English, arithmetic, and accounting over breakfast on her second day in England. In another infamous passage from her biography, she reports that “[h]e used, when making me, a grown woman, acquainted with them, to make me sometimes fall short at dinner if I did not guess the angle right of the piece of pudding I was helping myself to!” (Herschel 1876, 324-5)

<51>But if his behavior with puddings tends toward the petty-tyrannical, we see in this book, from Caroline’s side of the table, the rapid development of a brilliant astronomer. Turning its pages, we follow a trajectory that begins with simple geometrical proofs and moves through logarithms, algebra, rules for the making of astronomical instruments, spherical geometry, and other topics.

<52>The siblings’ shared profession defined their personal lives, as the history of this memorandum book’s composition shows us in textured detail. But looking beyond the book’s composition to its uses, it gestures toward the texture of Caroline’s computational work, that aspect of her professional life that tends to be ignored because it is too boring, too numerical, or is superseded by the observational work that she enabled. The information that she gathered in this book was put to daily use in the course of her work, traces of which are readily found.

<53>In one striking case, she provides a general proof for calculating the location of an object by using another, known object as a reference point. Caroline walks through the necessary calculations (including the use of logarithmic tables) in a clear and detailed manner but, most interestingly, adds a note at the bottom of the first page instructing the reader to, “For an example see 2d book of observations page 66” (Ransom MS M0672 36.25, p. 19). The example she is pointing to is her 4th comet, discovered on April 17th, 1790; and the calculation she is referring to is that for May 20, when she calculated its position by using Σ Cassiopeia as a reference point.

<54>This memorandum book, in other words, reminds us of all the calculations that Caroline performed in order to enable their observations, turn that raw observational data into formats suitable for analysis and re-use, and eventually prepare it for publication. Those computations formed the connective tissue between the ledgers that make up the Herschel archive; and as Caroline’s work product, they also served as the connective tissue for the observatory’s operations. But just as her computations require reconstruction in order to read the archive, so does Caroline’s computational labor broadly speaking require proper reconstruction if we are to understand the Herschels’ legacy to astronomy.

<55>This legacy was twofold: the transformation of astronomy into a natural science and, as this paper has argued, the prototypical industrialization of the field by centering data in the observatory. As we have seen, gender (and even class) dynamics were at play in the siblings’ successful attempts to build a singular observatory, which led to an unequal distribution of labor and credit, which come to light most clearly when we closely attend to Caroline’s computational work and seemingly minor innovations. But we have also seen that this inequality was not a certain outcome. There were slippages in the apparatuses of subordination, especially when everyone was busy trying to make the enterprise run (or figure out how it possibly could run). And these apparatuses malfunctioned entirely when William and Caroline accidentally rendered observation as mechanical as computation. Most significantly, however, in South’s imperfect speech to the RAS, we see a glimpse of a legacy which Caroline only briefly held, and which was lost to two centuries of subordinated knowledge workers: the recognition of her inventive and “unconquerable industry” as the equal of William’s (mechanized) “intellectual power.”