We had followed in the track of a shadow and had proved there was abundant light behind ___ the gleam of pleasurable excitements ___ the vision of things new and beautiful ___ the glow of accomplished resolution, and of surmounted difficulties.

Elizabeth Brown, In Pursuit of a Shadow, 1887(1)

<1>Elizabeth Brown (1830-1899), a highly regarded and successful Victorian woman solar astronomer, opens her narrative of scientific expedition and travelogue of her solar eclipse tour to Russia in 1887 by creating a sense of enigma. Her travel companion is introduced to the reader merely as L. and remains mysteriously identified as such throughout the narrative. We now know Brown’s companion was her cousin Martha Louisa Jefferys (Beckles and Kent). No less enigmatically, Brown published her account entitled In Pursuit of a Shadow (1887) anonymously as “By a Lady Astronomer.” Recognizing Brown’s use of mystery foregrounds questions about the role of women in nineteenth-century astronomy, and the strategies they used in their writing to establish and uphold what they saw as their ability and right to take part in the science.

<2> In 1887 Brown and Jefferys were “the first British women to [take] part (though unofficially) in a scientific eclipse team” (Brück, Women 155). Their journey recounted in In Pursuit of a Shadow saw them travel from Hull to Christiania in Denmark, then to Stockholm and on to St. Petersburg and Moscow, and then to Pogost, 472 miles from Moscow, returning via the famous fair at Nijni Novgorod and Smolensk. The epigraph to this essay is part of the closing paragraph of Brown’s In Pursuit of a Shadow. The 1887 eclipse observations in Russia were largely a disappointment as observation of totality was marred by cloud. Brown explained: “For a second or so we had a view of the coronal light, … and a glimpse of the rose-coloured prominences … but it was over almost before we had realized it” (In Pursuit 110). However, Brown ends her book by projecting an incredible sense of accomplishment. Some success in observing the coronal light was achieved, but there is more in her words than astronomical success. These two women organized their own expedition and traveled independently from ‘official’ expeditions to Russia, over sea and land, a destination not yet fully on the ‘tourist map.’ Russia was renowned for its difficulties for travelers, reportedly hampered by Russian bureaucracy, suspicion, and difficult terrain. Yet, Brown reports the accomplishment of “surmounted difficulties” and “pleasurable excitements” which reads as both astronomical and personal.

<3>Here, the eclipse and the tracking “of a shadow” seems metaphoric for the “shadow” under which women like Brown and her cousin took part in astronomy. It can also be read as a powerful metaphor for their agency in astronomical science and in society. The Sun, traditionally gendered male and all-powerful, giving light to the solar system and the Earth, is eclipsed, overshadowed by the Moon, which is traditionally gendered feminine and noted as drawing its light from the Sun. As it passes between the Sun and Earth, the Moon moves gradually across the face of the Sun until it completely hides the Sun, casting a shadow on part of the Earth. At totality, the feminine Moon obscures the dominating male Sun. The metaphorical implications of this event would not have been lost on Brown. In the same way, enigma with its ambiguity and resistance to closure, Emmanuel Levinas explains for us, “exceeds and disrupts the signified / signifier,” this “disturbance” inviting new meaning or interpretation (65, 63; Wolosky 272, 273). Enigma, for Levinas, “is a borderline phenomenon, located between the visible and the invisible, the said and the saying” (Waldenfels 78). The enigma in Brown’s narrative unsettles the reader from the start. The reader is confronted with an awareness of mystery and senses there are things in Brown’s writings that are both obscured and revealed ___ the unsaid and the said.

<4>Prior to important recovery work by Mary Creese (1998; 2004), Mary Brück (2002; 2009), Allan Chapman (2016), and Tracy Daugherty (2019) the role of women in nineteenth-century astronomy had been largely forgotten.(2) This was despite the important roles many women played in the science. Creese has paid special attention to Brown and her astronomical career. More recently, Joel Beckles and Deborah A. Kent’s 2024 essay “Eclipsed by History: Underrecognized Contributions to Early British Solar Eclipse Expeditions,” discusses Brown’s solar eclipse expedition to the West Indies in 1889 and its depiction in her Caught in the Tropics (1890). However, Brown’s In Pursuit of a Shadow has escaped sustained critical attention.

<5>In this essay, I seek to redress this gap. I argue that Brown’s first eclipse travelogue is double-edged. It both asserts the ability of women astronomers to take part in astronomical expeditions and produce accounts of their experiences, often as adventurers to less traveled lands, while remaining within the bounds of prescribed ideal Victorian womanhood. Victorian women were expected to keep a comfortable, happy, and restful home for men tired from working in the industrial and commercial hubs of Britain. A woman’s work was to support and care for her husband and family, as propounded by those such as John Ruskin, as well as Coventry Patmore, for whom the woman was the “Angel in the House.”(3) For many women, travel offered adventure and a release from the duties of the home and their expected “passivity and silence,” giving them a sense of power (Anderson 24). Moreover, vicarious travel through reading offered escape mentally from the patriarchal strictures of home; it also encouraged a new type of womanhood: courageous and adventurous.

<6>Brown played an active role in such encouragement, inviting other women to take up astronomy, and advising that solar astronomy was particularly suitable, even with the implicit acknowledgment that women were culturally defined as the weaker, more delicate sex: “The sun is always at hand. No exposure to the night air is involved and there is no need for a costly array of instruments” (“Programmes” 59). For Brown, women of any constitution and any financial standing could employ themselves in astronomical observation.

<7>My aim in this essay is to reveal how Brown’s life and writing interweave astronomy, and contemporary perspectives on issues of gender and the accepted role of Victorian women in astronomical science. This article contends that Brown’s career as a solar astronomer was shaped by the difficulties that arose for Victorian women within the male-dominated astronomical community, and through wider societal attitudes to femininity as reflected in In Pursuit of a Shadow. I argue that Brown used the genre of travel writing to negotiate the gender constraints of Victorian astronomy and culture.

Elizabeth Brown, “perseverance” and “humility”

<8>Miss Elizabeth Brown was the eldest daughter of Thomas Crowther Brown, a wealthy Cirencester Quaker wine merchant interested in astronomy, an active meteorologist, and Fellow of the Geographical Society. Educated by a governess and later largely self-taught, Elizabeth fostered an interest in science and astronomy from an early age. Using a tiny hand-held telescope, she marvelled at Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s satellites, soon learning the names of the stars and engaging herself with “the writing and teachings of her masters in the field” (“In Memoriam” 214). Brown assisted her father in taking daily meteorological readings and in 1871 took over his recording duties for the Royal Meteorological Society. Elizabeth became especially intrigued by solar research and conducted studies from her private observatory in her garden in the Gloucestershire village of Further Barton. Upon the death of her ninety-one-year-old father in 1883, when she was in her fifties, Elizabeth was released from domestic and caring duties and was able to travel and follow her interest in astronomy, pursuing meticulous research until her own death in 1899.

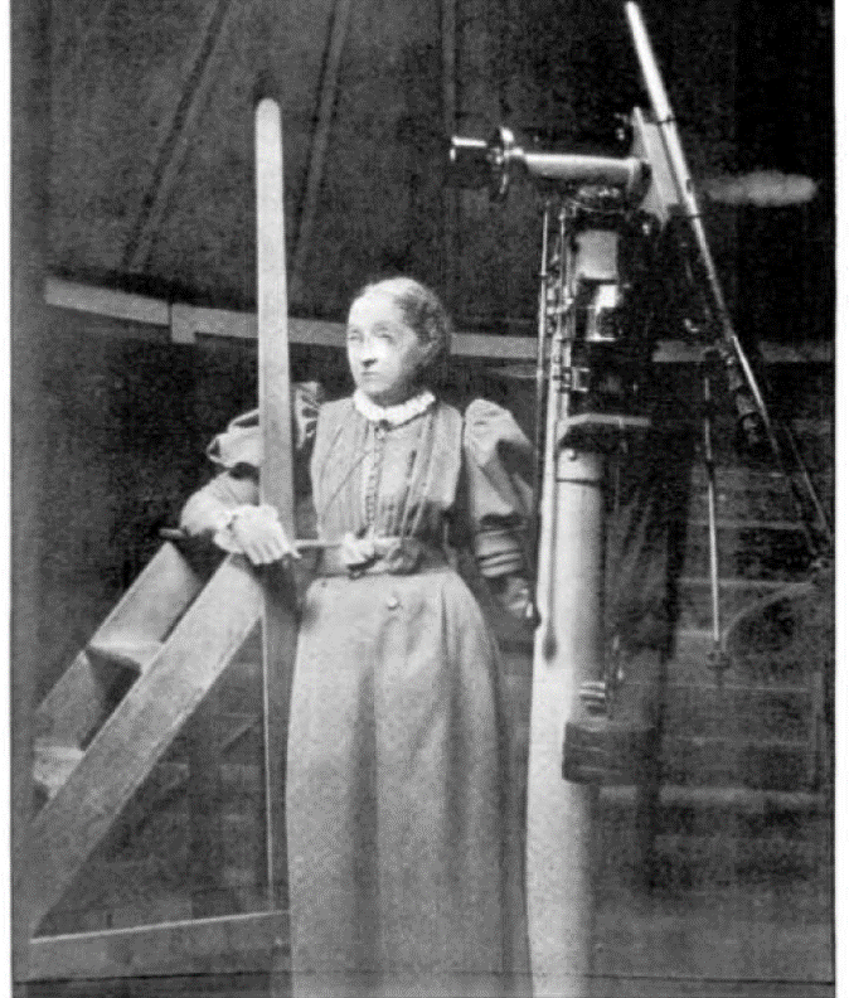

<9>Brown’s development as an astronomer followed her accumulation of necessary instruments. At first, she owned only a well-used 3-inch aperture refracting telescope and no observatory. She would observe the Sun, by projecting images from a telescope onto “a sheet of white cardboard placed on an easel in a darkened room” (Brown, “A Few Hints” 173). She later owned a 3½-inch aperture Wray equatorially-mounted refractor with a driving clock, and a 6½-inch aperture Calver reflector, a grating spectroscope which she could attach to the refractor, and an astronomical clock. Her refractor was kept in a small ‘Berthon’ observatory in the grounds of her home, and a second observatory housed meteorological equipment (Barton; Creese, “Elizabeth” 194; Fig.1).(4) A lady of private means and with ownership of an observatory and astronomical instruments, Brown was the female equivalent of the male “Grand Amateurs” who had traditionally dominated nineteenth-century astronomy (Creese, “Elizabeth” 193).(5) She was renowned for her “perseverance” and the thoroughness and reliability of her observations, together with her “humility” and no “desire or expectation of public recognition.” Her “service given purely for love of truth and for the love of work” earned her great respect in scientific circles (“In Memoriam” 214).

<10>Brown became a member of the Liverpool Astronomical Society, and from 1883 to 1890 served as its director of solar studies, publishing in its journal, for example, a “Solar Section Report” in 1885 and a paper “Auroræ and Sun-spots” in 1888. She was also a founding member of the British Astronomical Association (BAA) formed in 1890. Brown was instrumental in the setting up of the Association, having suggested its formation on the termination of the Liverpool Astronomical Society in 1890. She was the first director of the BAA solar section and worked with other observing sections of the BAA, including the lunar, variable star, and coloured star sections. Brown authored many scientific papers for the journal of the BAA and the Observatory magazine, mostly on her own and other astronomers’ solar observations, including reports on the total solar eclipse of August 9th, 1896. She also wrote seven annual reports for the solar section of the BAA between 1891 and 1897.

Women in Victorian Astronomy __ dancing and “friponnes”

<11>In the Victorian era, women’s activity in scientific organizations such as the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) was strictly controlled by their male members. Established in 1820, from 1833 it allowed women to be honorary members, but there were only three during the nineteenth century: Caroline Herschel, Mary Somerville, and Anne Sheepshanks. Similarly, from 1838, women could hear papers discussed on mathematics and physics at the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS). However, only four papers by women were read to this section in the nineteenth century.(6) Nevertheless, many women across the classes were avidly interested in astronomy, practicing the science, attending lectures and shows of orrery, and reading about the subject. Although the barring of women from learned astronomical science was noted by the BAA, which was set up to welcome those “who are, as in the case of ladies, practically excluded from becoming Fellows” of the RAS (Maunder 293). The practical experience of astronomy for women was often limited to the role of active assistants to male astronomers: women were the “invisible technicians” of astronomy (cited in Gates, Kindred 67).

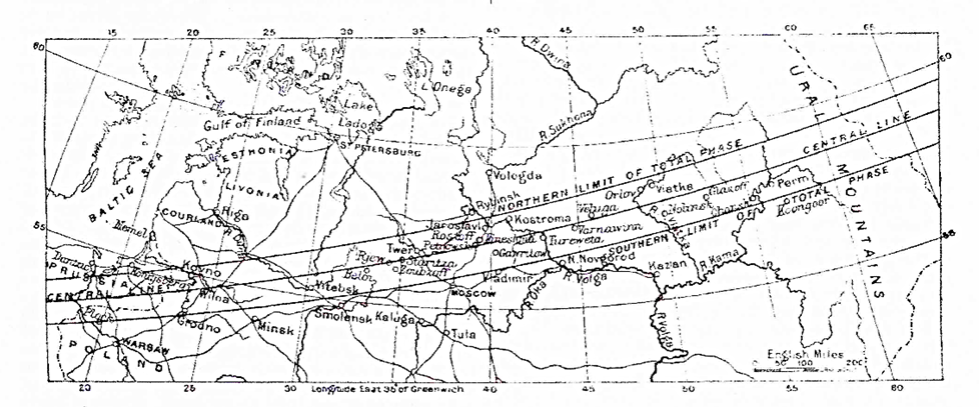

<12>At an 1892 meeting of the RAS, Brown was proposed for election as a member along with two other women astronomers, Alice Everett and Annie Russell. However, they were unsuccessful, failing to receive the two-thirds of the votes cast required for election. The minutes of the meeting recorded the Fellows’ discussion on the matter of admitting women. Mr Brett, a Fellow of the RAS, suggested that “it was practically a proposal to introduce into these dull meetings the social element, and all we shall require is a piano and a fiddle,” and “to lay down a parquet flooring, and I am sure many of my young friends will be glad to dance through most of the papers” (“Meeting” 216).(7) The statement by Brett suggests women would bring frivolity to the institution, preventing serious scientific debate. Women were often seen by male scientists as excessively emotional and religious, and intellectually inferior to men, resulting in inability to carryout objective scientific research. This was part of, and influenced by, what Barbara T. Gates in Kindred Nature (1998) has called “The Skirmish over Women’s Intellect” (13-22). Charles Darwin in The Descent of Man (1871) promoted the notion of male intellectual superiority: man was capable of “a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than woman can attain __ whether requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination” (2: 327). The biologist and anthropologist Thomas Henry Huxley tried to prevent women joining scientific institutions: “Five-sixths of women,” he wrote in an 1860 letter to the geologist Charles Lyell, would “stop in the doll stage of evolution” and cause “the degradation of every important pursuit with which they mix themselves – ‘intrigues’ in politics, and ‘friponnes’ in science. If my claws and beak are good for anything, they [women] shall be kept from hindering the progress of any science I have to do with” (356). In the late 1860s eugenicists including Francis Galton ranked motherhood as the ultimate role of women, given by Nature and requiring all of women’s energy. Herbert Spencer, in Education, Intellectual, Moral and Physical (1861) and The Study of Sociology (1873), wrote that women in evolution had been halted intellectually to conserve their energy for procreation. The psychiatrist Henry Maudsley declared in “Sex in Mind and Education” (1874) that a woman’s limited energy should be conserved for raising children rather than intellectual education (467).

<13>Around this time women began to publicly question notions of inequality, encouraged by reading popular magazines such as The Cornhill and Belgravia which inspired them to be interested in more than the home __ in science, literature, history, and travel. These publications encouraging a new model of woman as strong, independent and educated (McKenzie 3-4).(8) The botanist Lydia Becker, in a speech reported in the Englishwoman’s Review in 1868, asserted that “the attribute of sex does not extend to mind” and that present distinctions were “culturally determined” (484; Gates 17). Becker also published “On the Study of Science by Women” in the Contemporary Review, advocating the study of science for women to prevent them enduring lives of “intellectual vacuity” (388). Becker argued that scientific societies and universities should admit women so that the “stream of life” might be populated “with fish worth catching, instead of leaving nothing for the angler but the minnows and sticklebacks” (403; Gates, 18). The later decades of the nineteenth century saw the reductiveness towards women’s intellectual capacity challenged by the New Women who followed in the footsteps of those such as Mary Wollstonecraft renowned for her advocation of women’s rights, most notably in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) (Gates 21). Some learned societies in the late nineteenth century began admitting women, and Brown was a member of other eminent institutions: the Astronomical Society of Wales, the Astronomical Society of France, the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, and a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society (Creese, “Elizabeth” 196).(9)

<14>As Monica Anderson has shown at length in Women and the Politics of Travel, 1870-1914 (2006), women were considered too delicate to undertake the rigors of scientific exploration. Exploration was for men, so much so that proposals to admit women as fellows of the Royal Geographical Society in 1892 met with disdain and rejection by its male members.(10) In Victorian culture, explorers were heroes, and heroes were male. Equally, reportage of scientific expeditions was for men alone. Women’s travel texts were judged emotional, romantic and “low quality” lacking in geographic and scientific knowledge, and short of “any real interest for an informed and educated audience” (Anderson 21-23). This trivializing of women’s travel writing was common in Victorian culture and persists in the reviews of Brown’s In Pursuit of a Shadow. It was invariably received as a “pleasant little book,” “bright and cheery,” and as a “charming little book” (“Publications” 233; “Reviews” (a) 55). Additionally, a reference to Brown’s book as a “pamphlet” in Symons’s Monthly Meteorological Magazine in 1888 diminished its importance as a book, a pamphlet being a leaflet or small booklet (“Reviews” (a) 55). In Knowledge magazine in 1888, a reviewer found Brown’s text a “very pleasant, chatty and agreeable little book” written in a “delightful chatty manner, without the trace of guide-book padding” and “irrelevant quotation” used in modern day travel writings that rendered them “swollen bulky books.” However, despite this praise, the tone of the review, using such qualifying words as “apparently” and “appears” implicitly questioned the authenticity of Brown’s account of her expedition (“Reviews” (b) 236).

In Pursuit of a Shadow

<15>Elizabeth Brown made three eclipse expeditions. The first was to Russia in 1887, and the subject of her In Pursuit of a Shadow. There was considerable excitement among astronomers over the total solar eclipse of 1887. The path of totality was to “offer exceptional opportunities for observation from the circumstance that the track of the moon's shadow will be almost entirely a continental one,” in contrast to the eclipses of the previous four years when the shadow’s path had been “principally over the great oceans” (“Total Solar” 60). Visible to a limited degree in France and Germany, from Prussia the predicted 1887 path of totality stretched in a belt eastward across the Russian empire to Siberia and then across Northeast China and Japan (Fig. 2).

<16>In 1889-90 Brown and Jefferys traveled to the West Indies for the total solar eclipse on 22 December 1889. Their experiences on this journey Brown recorded in her second book, Caught in the Tropics. Her third eclipse expedition was to Norway in 1896 with other members of the BAA. Regrettably, Victorian women’s involvement in eclipse expeditions, has received scant critical attention. Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, in Empire and the Sun: Victorian Solar Eclipse Expeditions (2002), provides an in-depth study of eclipse expeditions of the period. However, he limits his research to expeditions officially sponsored by major institutions such as the Royal Society, the RAS, and the BAAS. Pang explains that he has “little to say about the role of women on expeditions.” According to him, women were “not major players in eclipse fieldwork, but they did appear on enough expeditions to deserve some discussion; however, British sources are notable for their steadfast silence on the role women played in the field” (3). In contrast, Beckles and Kent’s essay “Eclipsed by History” is concerned with “British solar eclipse expeditions in 1889 and 1919,” and the “ways in which contributions of women and of people in colonized lands have been underrecognized by the expeditioners and in subsequent narratives about them” (“Eclipsed”).

<17>Victorian eclipse expeditions played a significant role in furthering astronomical knowledge. The aim was to gather more information about the physical nature of the Sun. Notably, in 1860 Warren de la Rue photographed the rosy prominences of the Sun’s corona while in Spain observing the total solar eclipse. In India in 1868 the chemical element helium was discovered simultaneously by Pierre Janssen and Joseph Norman Lockyer while observing the spectrum of the Sun’s chromosphere during totality. As Toner Stevenson remarks in “Why Observe Eclipses?” in Eclipse Chasers (2023), “eclipse expeditions were undertaken in the quest to be at the forefront of explaining the nature of our closest star, the physical relationships in our solar system and the laws of physics, which our universe demonstrates” (4). Developments in observing equipment such as photography and spectroscopy enabled advancement in observation, measurement, and recording of data.(11) Astronomers sought to improve navigation by producing more accurate readings of solar and lunar motion. They also aimed to test the accuracy and abilities of observational techniques, methods of calculation, technologies, and theories. These hopes extended beyond eclipse observations. Astronomers viewed their eclipse experiences as invaluable training for the observation of the transits of Venus which were to occur in 1874 and 1882.

<18>Other major developments played a part in these scientific observations. In Russia, for example, improving infrastructure with the expansion of telegraphs and railway networks facilitated communications and transport. In fact, the Russian telegraph system was seen as a great advantage to the astronomers taking part in the solar eclipse expeditions of 1887: “The path of totality coincides in a most remarkable manner with the lines of the Russian overland telegraph,” and it was hoped that “some discovery, either in solar research, or of a comet or intra-Mercurial planet, might receive in this manner the most satisfactory confirmation and development” (“Total Solar” 61). The improvements in the Russian railway network made reaching places along the long path of totality across the Russian empire more feasible. The railway line between St. Petersburg and Moscow opened in 1857, and as the Russian network expanded it enabled faster connections to Siberia. John Murray’s 1868 edition of the guide Handbook for Travellers in Russia, Poland and Finland advised travelers that “the journey to St. Petersburg may be performed throughout the entire distance by rail in three and a half to four days …. A railway connects Moscow with St. Petersburg; and express-trains convey the European to meet the Asiatic at the fair of Nijni-Novgorod” (v-vi).

<19>Although they were not part of any officially sponsored team in Russia, Brown and Jefferys stayed with Professor Theodor Bredichin, Director of the Moscow observatory who had a private observatory at Pogost. Bredichin’s observatory was two kilometres from Kineshma and close to the central line of totality.(12) Bredichin had invited the two ladies to his home and to be part of the observing group. An 1887 article on the upcoming eclipse in the journal Nature reported that Bredichin had also extended an invitation of “hospitality” to the RAS for “two English astronomers” which the society accepted on behalf of Father Stephen Perry and Dr. Ralph Copeland (“Total Solar” 60). But despite the invitation to Brown and Jefferys, very much an honour and recognition of Brown’s ability and standing as a solar astronomer, the Nature article made no mention of it. Although largely invisible in official records of the 1887 eclipse, Brown and Jefferys were mentioned in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1887 in a report on the eclipse expedition to Russia by Perry, who knew Brown through their mutual membership of the Liverpool Astronomical Society:

Most fortunately we were joined a few days before the eclipse by Miss Brown, of the Liverpool Astronomical Society, and her cousin Miss Jeffreys [sic], and the latter most obligingly and most efficiently took charge of the cameras of my spectroscopes during totality, thus leaving me entirely free to attend to the two chronographs. (53)

Jefferys thus appears to have had astronomical experience and had undergone “severe training” with Perry at Pogost in readiness for the eclipse (In Pursuit 108).

<20>In the authorial attribution of In Pursuit of a Shadow, as in Caught in the Tropics, Brown anonymizes herself as “A Lady Astronomer” and, throughout, her cousin Jefferys as “L.” A sense of secrecy appears on the very first pages of her account:

My companion, whom I will call L., lived in one of the Northern Counties and we were bound for Russia to see the great Solar eclipse of August 19, so that it may be imagined we met under circumstances of pleasurable excitement not unmingled with awe at the prospect of countries strange and unknown and of people of unknown tongues. (In Pursuit 1)

This passage sets the reader up for the air of enigma about the women's expedition to Russia that persists throughout Brown's book. To be in “pursuit of a shadow” suggests that something fleeting is being chased; in fact, not all solar eclipse expeditions produced successful observations of totality. There was awareness among astronomers that atmospheric conditions, equipment failures, or failings in technique by astronomers could prevent good observations.

<21>Brown’s opening passages also suggest a sense of delight at the prospect of travel and enthusiasm, if not slightly daunted, at the expectation of encountering the unknown. Brown goes on to express her concern for reports she has had about travel in Russia with their “slender linguistic acquirements”:

Nor had our friends and acquaintance spared us the usual amount of alarming prophecies, first and foremost among which stood the terrors of Russian Custom-houses, stern officials and a perpetual background of police supervision. (1-2)

Their “counsels” had advised on their packing, adding even more concern to the situation awaiting the travelers in Russia:

Books had been interdicted by one friend. Sketching materials viewed doubtfully by another, while a third anxiously specified that nothing was more important than the loose arrangement of all corners in our trunks in preparation for invading hands; added to this my beautiful little telescope, the loan of an astronomer friend, in its oblong black box, certainly presented a suspicious appearance almost suggesting dynamite! (2)

Detectable here is an air of apprehension, of vulnerability that both reflects the contemporary cultural view of travel to Russia and fits with the prevalent image of women as weak and likely to come to harm, or to have their belongings mistreated or stolen. As the narrative progresses Brown is keen to rebuke this ideology yet maintain a sense of female vulnerability. She establishes that their luggage arrived safely in St. Petersburg and was inspected by customs officers and remained unharmed: “Once more our dread of any trouble proved entirely fallacious __ they only just opened our two large boxes, while the telescope, and even L.’s little bag of books, were passed without demur” (In Pursuit 42). However, Brown recalls that when arriving in Smolensk both ladies were unnerved and felt at risk on their own in the droskies as they transferred to their hotel from the train station. Both the droskies “were dirty” and they were separated into two droskies when they would “most gladly have been together,” especially as “one at least of the drivers” was “shady looking.”(13) Brown details: “we hardly seemed for some time to be approaching any town” and when they did the “drivers turned into a street with no lamps at all,” and where “L. who led the way, confessed to having felt just a little creepy, a horrible story of a lady who was murdered by a drosky-driver, coming into her mind, so that she kept anxiously looking back to be sure that I was following” (In Pursuit 121-22).

<22>Brown and her companion took part in this expedition at a time when more Victorians were beginning to visit Russia. The early Victorian period had inherited a long-seated strained relationship between Russia and the rest of the world. This, and the Crimean war, made Russia particularly unpopular with travelers. Where travel to Russia is discussed in travel literature of the period it is invariably portrayed as a hostile place, where foreign travelers were met with suspicion and the need to negotiate difficult bureaucratic conditions to enter and move around the country. By the 1860s travel to Russia became easier and faster and grew in popularity. This is evidenced by the need for a comprehensive guidebook identified by the firm of John Murray who issued substantially revised editions of their 1849 Hand-book for Northern Europe; Including Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia as Handbook for Travellers in Russia, Poland, and Finland in 1865 and 1868 (Murray, “Preface” 1865 edition).(14) Many Victorian women traveled to Russia and some left accounts of their experiences, such as Elizabeth Rigby, in A Residence on the Shores of the Baltic. Described in a Series of Letters (1841), published anonymously.(15) Another example was Mary Ann Pellew Smith’s Six Years' Travels in Russia (1859), published anonymously as “By an English Lady.” Missionary, nurse, and explorer Kate Marsden traveled 11,000 miles to Siberia in 1890 to establish a leper colony with the aim of finding a cure, publishing On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers in 1891. Women also went to Russia as governesses to teach English or accompanied husbands and male family members who toured the Russian empire for commercial and intellectual interests, as well as those following their passion for the natural sciences (Pethybridge).

<23>With the popularity of the European Grand Tour, women had often traveled and by the mid-1800s had traveled increasingly independently. While this seems contrary to the Victorian conventions of womanhood, it had been recognised by Elizabeth Rigby in her 1845 article “Lady Travellers” that domestic virtues equated with the “four cardinal virtues of travelling __ activity, punctuality, courage and independence had already been developed at home, enabling [women] to achieve so much abroad” (102). These virtues when detailed in travel writing work to establish a sense of home values while traveling abroad. Brown’s In Pursuit of a Shadow always details the time schedule of the women’s experiences when touring various sites, catching trains, steamboats and carriages and the precise times of meals – punctuality is of the essence in the narrative. Their days were planned out to make the most use of their stop-over times in the places en-route to Russia and while in Russia. Each day is full of “activity,” visits to sites of interest, tours by carriage through the villages and countryside, walks, sketching, and preparations for the eclipse observation. Although it was not an official eclipse expedition, Brown and Jefferys were highly organized in their preparations. Their travel itinerary was coordinated in fine detail, the timing, tickets, and hotels were arranged in advance of travel. Brown had “a personal interview” with the “kind Russian consul in London” (In Pursuit 42). They had researched the countries they were to travel through and learnt some of the languages. Jefferys had prepared a book of words and phrases that would prove invaluable.

<24>Such organizational skills reflect women’s role as the managers of the home. Ideal feminine attributes continue throughout In Pursuit of a Shadow. Brown details domestic arrangements in precise detail. Rooms are described right down to the quality and comfort of the bed linen. The food they were served, and who by and in what manner is detailed __ all concerns that should occupy them in the domestic sphere at home. Brown and Jefferys also showed their observance of ideal feminine piety. They attended church services, for example, on board the steamboat to Christiania and while in Stockholm they attended the Swedish Lutheran church of Santa Clara for the Sunday service, and in St. Petersburg, Kazan cathedral.

<25>Descriptions of the landscape they experienced abound in Brown’s text. The landscape is described in a picturesque manner in terms of its beauty, keeping it within suitable feminine aesthetic categories. Beauty is associated with the feminine in terms of Edmund Burke’s gendering of the idea of the beautiful as feminine, and the sublime danger which “demands bravery” as masculine, in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757; Mellor 107-109). Brown keeps the scenery domesticated by employing suitable and familiar feminine genres and methods such as the “feminine picturesque” and “picture-writing” (Gates 168-69). Often Brown portrays the landscape as a word-picture, sketching the view for the reader in terms reminiscent of a watercolor painting. Brown describes the view as they journey by boat from Stockholm to Cronstadt on their way to St. Petersburg using these techniques:

Before noon we reached Hango, with its small hamlet of wooden houses, and then more islands, and yet more, pine-clothed or barren, but all picturesque. The sea was almost calm, and the white light of the sky reflected in it gave it a beautiful glassy appearance, and in this glassy sheet of light were set these innumerable islets, light and dark, grey, purple, green, violet ___ those farthest away showing only as dark lines in the water. (In Pursuit 35)

Sketching and watercolor painting were considered suitable feminine accomplishments for Victorian women. Brown and Jefferys often followed the activity while traveling and Brown describes their regular sketching trips. On one such occasion, while at Pogost, Brown describes how she seeks the perfect subject for a sketch:

I looked in vain for any subject for my pencil, anything but a coloured sketch, and that very much idealized, being out of the question, so I passed on, …. and made for a group of young saplings, under whose scanty shade I planted my camp stool, and … I made a rough sketch of the Professor’s house, which was visible in the distance, with its row of Corinthian pillars on one side, showing white among the surrounding shrubs. (In Pursuit 104-105)

<26>Domestic dwellings are a fascination for Brown, and she goes into detail about their gardens, often comparing them to English garden styles. Brown described the “constant succession of pretty views” as they “steamed down the wide fiord or arm of the Baltic”:

These banks were dotted with villa houses, with their verandas and gardens, not exactly after the orderly and cultivated style of our English gardens, but still looking tempting from the water, with winding paths, shrubs, flower-beds and summer houses, and always seats and tables under the trees. (In Pursuit 23)

<27>Flora and fauna are described in detail. Writing about the desolation of many of the places they pass through on the train from Christiania to Stockholm the black crows are a particular interest for Brown:

The country seemed as often as not peopled only by the hooded crow (Corvus Cornix), and these birds we watched with great interest, as they are rarely if ever seen in England. They are large birds, the size of our common rook, with black and grey plumage, and are allied to the carrion crow. (In Pursuit 17-18)

Birdwatching became regarded as a genteel occupation for women in the late nineteenth century. It was appropriate for women to focus on songbirds and the domestic nesting habits of the varied species. Scientific ornithology and collecting was male-dominated as it involved wealth, hunting, and shooting. Victorian women wrote birdwatching guides, bird poems, books, and articles often with strikingly elaborate illustrations.(16)

<28>Brown and Jefferys’ botanical knowledge is clear in In Pursuit of a Shadow: Brown identifies species of plants and trees. Botany was a popular and accepted scientific pursuit for Victorian women as has been well documented (Shteir 1996, 1997; Le-May Sheffield 2001). From the eighteenth century, botanical knowledge was regarded as enlightening for women, making them good conversationalists, better educators for their children, and accomplished illustrators of the beauty of the natural world. Women read and wrote books and essays on botany, especially for other women and children, and attended lectures about botany, collected and drew plants, and carried out microscopical studies of specimens. Taking a carriage drive from Christiania to Frognersæter Brown reports: “On leaving the city, the road passes through open fields with many flowers by the road sides, among which we noticed hare-bells, yellow bedstraw, white chrysanthemums, and one species of bright coloured geraniums” (In Pursuit 9).

<29>Brown wrote In Pursuit of a Shadow at a time when astronomy was becoming more technical and professionalized, and subsequently even more male-oriented. As a result, some astronomical writers saw a gap in the market for more straight forward, clearly written books, avoiding the complexity of the subject, suitable for amateurs, children, and beginners. Women writers such as Agnes Giberne adopted a popular storytelling mode of writing. While others such as Richard Anthony Proctor and Robert Stawell Ball tapped into the popularization of astronomy, writing for a wide audience.(17) Brown was also writing for a popular audience in a ‘pre-professionalization mode,’ that was as much about the adventure of travel and expedition, as about the science of astronomy. By employing the genre of travel writing, Brown negotiated the increasingly restrictive gendered nature of the professionalization of science. This genre enabled women, as Lila Marz Harper argues, to “gain a foothold in a traditionally masculine-dominated field, even as that field became increasingly more restrictive,” and move beyond the appropriate literary fields of home and family. The divergency of subject matter in travel narratives enabled “its interactions with other kinds of expression” (Harper 14; Medeiros 5-6; Pratt 11). However, Brown attempts to keep her book within the acceptable female sphere by not encroaching on the male domain of professionalized astronomy. Although Brown’s In Pursuit of a Shadow is an account of an eclipse expedition there is little discussion of scientific matters. That having been said, there are some passages where Brown describes the night sky, showing her astronomical knowledge. For example, during their train journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, Brown describes the heavens: “Then came a vision of the silvery moon, now low in the heavens, which glittered through and between the dark stretches of the pine-woods, while in the west Arcturus hung out his red lamp” (In Pursuit 60). Even so, such passages remain picturesque and painterly. Although the reader is told about the equipment, arrangements, and preparations for the eclipse observations, overall, astronomy is rare in Brown’s account of their expedition. In fact, Brown is self-effacing of her knowledge and standing in the science. She records her feelings of humility when in the presence of the male astronomers representing the RAS, also staying in Professor Bredichin’s home. Brown explained: they “were so infinitely above me in scientific status that I could but feel the amount of my own self-acquired knowledge small indeed in comparison, and quite inadequate to place me as a co-worker on their higher level” (In Pursuit 90). So extreme is her humility that Brown hides her acquaintance with them by referring to them only as Father P. and Dr C. (In Pursuit 102, 106).

<30>These expressions of domesticity, ideal femininity, vulnerability, and humility add up to a sense of caution in Brown’s In Pursuit of a Shadow, tempering the appropriation and encroachment on male scientific authority and expedition, reflected in society and in male travel writing. Brown and Jefferys’ journey and idea of self is clearly influenced by nineteenth-century notions of women’s appropriate place and identity. Brown shows how women could operate within the bounds of the dominant ideology yet offers an alternative narrative for women. In adopting the role of the scientific expeditioner, and astronomer, Brown demonstrates how Victorian women could escape the cultural fixedness of their position.(18)