I am speaking of a peculiar sense, ineffable, indescribable, but which everyone knows again who has once had it, and which to many of us grown into a cherished habit—the sense of being companioned by the past, of being in a place warmed for our living by the lives of others.

—Vernon Lee, “In Praise of Old Houses,” Limbo and Other Essays, 29

<1>In Vernon Lee’s works, the experience of inhabiting a space gets intimately entwined with its temporal layers.1There is a constant slippage between the evanescent moment of the present in which the experience is located, and its invisible anchorage in the sediments of the bygone. Italy is one of the key sites where the incursion of the past into the present is located in her writings, featuring prominently across her oeuvre: in her aesthetic treatises such as Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy (1880), in her travel essays, such as Limbo and Other Essays (1897) and The Spirit of Rome: Leaves from a Diary (1906), and in her fictional writings, such as Hauntings (1890). This paper shows that the eighteenth-century Italy, the site of her first aesthetic treatise, plays a key role in disrupting the temporal enclosure of the late-Victorian period when she was writing her short story “A Wicked Voice,” a part of her collection of short stories Hauntings.

<2>In “A Wicked Voice,” a nineteenth-century Norwegian singer Magnus, “a follower of Wagner” (155), gets obsessed with the voice of the eighteenth-century Italian castrato singer Zaffirino amid the “moral malaria” of Venice (156).(2)Magnus deeply abhors the musical mores of the eighteenth-century Italy, even as he imitates it with learned virtuosity. The music of the past becomes increasingly corporeal during his Italian sojourn, and infects him with a deadly malarial fever. Carlo Caballero has explicated the haunting presence of the past in the text in terms of “the uncanny mutability of a voice born of castration” (389). Patricia Pulham has read in the figure of the castrato the “empowerment for the lesbian writer who must masquerade as male and negate her sexuality” (435). Catherine Maxwell has traced “the spectrality of Venice” to Whistlerian impressionism (231), and the fame of the city as a site “of sexual intrigue” (233). While I expand upon the existing scholarship to underline the entanglement between sexuality and aestheticism in the short story, I foreground the crucial role of malaria in shaping the vocabulary of haunting.

<3>Far from being a mere metaphor, the “moral malaria” in the text is materially related to the prevalence of the fever disease in Italy, as I show by reading contemporary medical literature and visual artefacts alongside the text. Malaria becomes key to the undoing of Magnus—both in terms of his masculinity and his secure footing in his own time. Malaria as a disease associated with the temporal past of the Italian peninsula in the nineteenth century renders the haunting music of the past corporeal—a corporeality that has largely eschewed any scholarly attention. I build upon Elizabeth Freeman’s reading of “the stubborn lingering of pastness” as “a hallmark of queer affect” in Time Binds (8) to analyze what I call the “malarial queer,” a palpable sense of the past infecting the present. I analyze the interlink between malaria and the music of the past by reading Lee’s travel essays and writings on aesthetics alongside “A Wicked Voice.” My paper is in conversation with Jessica Howell’s work on the “foreboding atmosphere” (40) of malaria-ridden Italy in Charles Dickens and Henry James. The paper underlines the spatial significance of Italy as a site of imperial decay, which segues with its reputation as the preeminent site of malaria, as the disease becomes aligned with political decline in the late-Victorian medical imaginary. This inscription of degeneracy upon malaria anticipates its contemporary understanding as the affliction of “underdevelopment.”(3) The textual Italy of “A Wicked Voice” presents a temporally infectious site—reaching back to the cultural past of the land as well as forward to the designation of malaria as a disease of backwardness. Malaria embodies the temporal volatility of Italy upon the pages of a late-Victorian English text. My analysis of malaria in “A Wicked Voice” extends the “limiting views of both geography and period” (376), upon which the disciplinary premise of Victorian Studies rests. Thereby, the paper recovers the often-forgotten genealogy of undoing the Victorian within the textual corpus of the Victorian literature itself.

“Borderland of the Past”: Italy and the Malarial Queer

<4>For the late Victorian reading public, the Italian peninsula was the land of many pasts— strewn with the classical ruins, the remnants of the Renaissance, the signposts of the Grand Tour, the textual cues of the Romantic sojourns of Lord Byron or Horace Walpole. Writing primarily for an English readership, for Lee, Italy came to stand for a civilizational past: “For Italy, beggared and maimed (by her own unthrift, by the rapacity of others, by the order of Fate) at the beginning of the sixteenth century, was never able to weave for herself a new, a modern civilization…” (Euphorion, 16) (parenthesis in original).(4) With her deep personal and scholarly engagements with Italy, her writings are far from the habitual trail of the burgeoning business of Victorian travel in Italy, dominated by Murray and Baedeker handbooks.(5)Yet, she invokes the textual map of continental travel when she asserts that “we live ourselves, we educated folk of modern times, on the borderland of the past, in houses looking down on its troubadours’ orchards and Greek folks’ pillared courtyards” in her “Preface” to Hauntings (39). Her fiction plays with the debris of these many pasts to construct its ghosts¾“the ghosts of a historicism largely untroubled by supernatural design” (Leighton, 1). The burden of the past in Italy not only rendered it ghostly, but also inscribed the blight of malaria upon it.

<5>In “A Wicked Voice” the narrator-protagonist Magnus is not only haunted by the voice of the dead singer Balthasar Cesari, “nicknamed Zaffirino” (157), during his stay in Venice, Padua and Mistrà, he literally catches a deadly fever. This depiction of disease in the text relates to the image of Italy as the land of malaria in the aftermath of Scottish geologist John MacCulloch’s medical treatise Malaria (1827). He finds “the throne of Malaria” amid the “refreshing streams,” “flowery meadows” and “glassy lakes” of Italy (6). He explicitly suggests that the “idle curiosity” in exploring the “classical ruins” of Italy “to seek a reputation for taste” has resulted in numerous cases of malaria (376). The link between imperial decline, signaled by the Roman ruins, and malaria features in the writing of Italian malariologist Angelo Celli as well: “with the decline of the Empire, and after the transference of its seat to Byzantium, malaria increased” (6). Vernon Lee draws upon these well-known associations among Roman antiquity, beauty, and the fatality of malaria in shaping the “malarial queer” in the short story, where temporality itself becomes infectious. Jessica Howell in her reading of malaria in “Victorian travel literature” finds “the Italian environment” to be “mired in a temporal past” that “does not threaten American and British cultural ascendancy” (31-32). While the depictions of malaria and the pastness of Italy remain entangled in “A Wicked Voice” as well, their imbrication threatens the cultural supremacy of the contemporary moment.

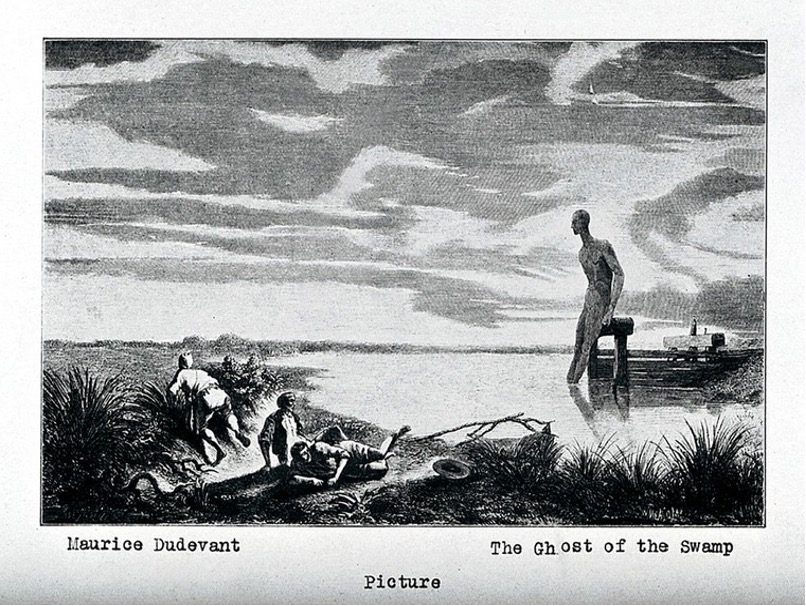

<6>The dedication of “A Wicked Voice” to “the last song at Palazzo Barbaro” (154), owned by the American expatriate Curtis family, and its opening scene at a “little artists’ boarding-house” where Magnus encounters the engraving of Zaffirino, brought by an “American etcher,” (156) illustrate the late-nineteenth-century world of foreign travelers and artists in Venice.(6) His initial relationship with the past is one of conscious imitation and study “of the great dead masters” whom he abhors with “the doggedness of hatred,” as he remains dedicated to Wagner “the great master of Future” (155).(7) Yet, the presence of the music of the past appears to be overwhelming in the city, as “under the full moon,” the city “seemed to swelter in the midst of waters,” “exhaling” some “mysterious influences,” and making the “brain swim and the heart faint” (156). As an exhalation of the stagnant water, malaria becomes the conduit of “those languishing melodies, those cooing vocalizations” one finds “in the musty music-books of a century ago” (156). At one level, the text seems to merely interlink the Italian word “mal’aria” or “bad air,” understood to be a cause of various diseases, and “aria” or a self-contained musical piece.8 On a closer probe, one finds the influence of medical ideas from the eighteenth century on the imagery of contagion fleshed out in the text. The notion of the moon affecting the febrility of the Venetian lagoon draws upon the eighteenth-century notions of medical astrology which analogized the impact of sun and moon upon the tides with their presumed influence on bodily fluids.(9) The depiction of the exhalations released by the city harks back to the eighteenth-century Italian physician and natural philosopher Giovanni Maria Lancisi’s definition of malaria as “paludum effluvium—marsh exhalation—because he believed a marsh, lake or some other form of stagnant water necessary to its production” (Caldwell, 55). The three-way association among malaria, stagnant water bodies, and temporal stasis pervades the popular imagination of the nineteenth century, as the engraving of the French artist and entomologist Maurice Sand, titled “The Ghost of the Swamp” suggest:

Vernon Lee draws upon this aesthetics of malaria as a malady of time in fashioning the remarkable coupling of infection and eeriness in “A Wicked Voice.”

<7>The seemingly disparate worlds of music and medicine interlace seamlessly the more the image and the voice of Zaffirino become incarnate realities in the story of Magnus. Magnus explicitly registers his dismay at the celebrity of the “voice”¾ “not invented by the human intellect, but begotten of the body”¾ in the eighteenth-century music (156), even as he recounts the superiority of “Zaffirino’s vocal gifts than those of any singer of ancient or modern times” (157). The legendary vocal prowess of Zaffirino is reinforced in the Venetian Count Alvise’s story about the untimely death of his great grandaunt Procuratessa Vendramin by his voice: “he went and killed her with those songs of his, with that Aria dei Mariti [The Husband’s Air] (162). This high praise of Zaffirino’s voice resonates with the description of the castrato singer Farinelli in Lee’s Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy: “[h]is voice, it was universally acknowledged throughout Europe, had been infinitely more voluminous, extensive, and beautiful than any other that had ever been heard before or since” (111).(10) Magnus’s characterization of Zaffarino as an “effeminate beau” (157) invokes the interrelationship between “the celebrity of the castrato” and “the longstanding perception of the Italian peninsula as a region that openly tolerated, if not actively promoted, homosexuality” in the eighteenth century (Findlen, 28). While the narrator remains resistant to both the musical and sexual differences of the past, the past possesses him physically and musically, creating “horrible palpitation,” “sending the blood to my brain,” and making him sing “Biondina in Gondoleta [The Blonde Girl in the Gondola], the only song of the eighteenth century which is still remembered by the Venetian people” (162). A contemporary article titled “On Nervous Palpitation of the Heart and Its Treatment,” published in The Therapeutic Gazette, relates “palpitation” to the “engorgement of spleen” in malaria (560). In effect, malaria turns Magnus, the virtuoso of the future music, into a hostage of the musical past: “I sing it, mimicking every old-school grace; shakes, cadences, languishingly swelled and diminished notes” (162-163).

<8>The atmospheric details of moonlit Venice become merged with the ghostly voice of Zaffirino to embody malaria in the text: “it was as if there arose out of its shallow waters a miasma of long-dead melodies, which sickened but intoxicated my soul” (163). In Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy, Lee underlines the importance of Venice in the musical world of the Italian eighteenth century: “Venice, being the city where music was cultivated at great expense, was naturally, the one where most was done in the way of music publishing, nearly all the printed music in Italy coming from Venice” (102). In her essay “Out of Venice At Last,” she delineates the very experience of residing in Venice in musical terms: “the things which Venice offers to the eye and the fancy conspire to melt and mar our soul like some music of ungraspable timbres and unstable rhythms and modulations” (340) (emphasis in the original). Understandably, in Venice, music of the past spills over the archive and becomes a part of the living soundscape of the city. In a “very strange dream” (163), the story of Count Alvise comes alive as “that exquisite vibrating note” of Zaffirino “went on, swelling and swelling” until a “horrible piercing shriek,” purportedly that of Procuratessa Vendramin, followed by “a gurgling, dreadful sound,” wakes Magnus up (165). The more Magnus attempts to shake off the haunting melody of the past, it appears to be inextricably related with the malarial atmosphere of Venice. He goes on a solitary row in the moonlit canal in a bid to enter the “heroic world” of Paladin Ogier (166). Yet rather than finding an inspiration for the “heroic, funereal” theme of his Wagnerian opera, he gets ambushed by the baroque music of the Italian eighteenth century:

Suddenly there came across the lagoon, cleaving, chequering, and fretting the silence with a lacework of sound even as the moon was fretting and cleaving the water, a ripple of music, a voice breaking itself in a shower of little scales and cadences and trills. (166)

The entwinement between the visual pattern of the moonlight and the aural motif of the music creates “faintness” in the narrator (167). His attempts to fill his ears with “yells and false notes,” with the Neapolitan folk song La Camesella for instance, come undone as a voice arises “from the midst of the waters” and gradually “taking volume and body, taking flesh” emerges “triumphant” as the keynote of the Venetian waters (167). The text associates the ghostly voice with “the blue and misty sea” (166), an atmosphere often linked with malaria— “condensed atmospheric moisture, in the shape of mist or fog, may carry malaria,” as the American physician and bacteriologist George Sternberg suggests (58). Malaria lends the spectral voice body and flesh and turns it into a corporeal agent of contagion. This embodied and contagious body of the past music, or what I call the “malarial queer,” does not have a determinate gender. Therefore, the gondoliers have a hard time determining “whether the voice belonged to a man or to a woman” (170). Patricia Pulham rightly argues that “perhaps the voice’s most threatening quality is its androgyny” (432), which not only upends the gender division of the Victorian period, but also overturns the temporal borders between the past and the present, as I show in the last section of the paper.

“The Ghost of Man”: Malarial Embodiment and Victorian Untimeliness

<9>In the final section of the short story, the fever-ridden body of Magnus, retreating from the “air of the lagoons” and “the great heat” of Venice into the countryside, increasingly become phantasmal, whereas the voice of Zaffirino acquire substantiality (171). The portrayal of the deteriorating health of the narrator in Italy draws upon contemporary medical ideas about the Italian climate. In Change of Air (1831), the British surgeon James Johnson underlines the delusive nature of the Italian climate, which is “beautiful to the eye and pleasant to the feelings” but “destructive to health” (51). In Malaria, MacCulloch calls the inhabitants of the Italian climate “the ghost of man, a sufferer from his cradle to his impending grave” (7). Malaria, embodied in the narrator, becomes key to the undoing of his late-Victorian comportment.

<10>In his brief sojourn in Padua, Magnus momentarily finds respite from the climate of Italy into its musical history. While witnessing a grotesque musical performance at St Anthony’s, he recounts the musical history of the Italian eighteenth century: the musicologist Charles Burney, the Italian castrato singer Gaetano Guadagni, the German composer of Italian opera Christoph Willibald Gluck, and so on. It is an attempt to historicize from the distance of the present without being infected or haunted by the past. However, Lee attends to “the historical otherness of an object” (Mahoney, 46), restoring contagion to the text, as the presumed voice of Zaffirino emerge inside the empty church, “enveloped in a kind of downiness,” and spread “enervating heat” through the body of Magnus (173-174). If “naked flesh is bound into socially meaningful embodiment through temporal regulation” (3), as Elizabeth Freeman propounds, the untimeliness of Zaffirino’s voice becomes a key component of the subversive gender politics in “A Wicked Voice.”

<11>The narrator’s final stay in the Villa of Mistrà is when the “sickliness becomes literal,” according to Leighton (9). While malaria suffuses the descriptive registers of both Venice as a space, and the music of the past, in Mistrà, the narrator is explicitly cautioned against “the fevers of this country,” the “dreaded” mosquitoes, and “moonlight rambles” (176).(11) The villa is presented as a site of temporal stasis: “I felt as if I had been in this long, rambling, tumble-down Villa of Mistrà…all my life” (174) in the same way as Venice becomes a stagnant repository of the past in the earlier part of the text. However, rather than being tied to the spatial aesthetic, here malaria becomes an affliction of remembrance: “I remembered all those weedy embankments, those canals full of stagnant water, the yellow faces of the peasants; the word malaria returned to my mind” (177) (my emphasis). James Johnson marks the “unsightly and unearthly compound” of “yellow” and “sallow” as a key characteristic of the malarial “physiognomy” in Italy (78). Malaria reaches beyond individual remembrance in its indelible mark upon the collective embodiment in the longue durée.

<12>The recollection of malaria triggers the emanation of the sound associated with Zaffirino—“a note high, vibrating, and sweet,” as well as the reminiscence of the fatal music that presumably took the life of Procuratessa Vendramin in Count Alvise’s story in the same palace (177). After all, the narrator recognizes the voice that has long persecuted him amid the “little galleries or recesses” (178) for musical performance inside the villa dating back to the Italian eighteenth century. As soon as he recognizes that “this voice was what I cared most for in all the wide world,” his own body loses its discreet identity and becomes an embodiment of malaria: “I too was turning fluid and vaporous, in order to mingle with these sounds as the moonbeams mingle with the dew” (179). The scene of Vendramin’s purported death is repeated, with her “death-groan” mingled with the “long shake” of the voice (180). When the narrator eventually enters the room associated with the voice, all he finds is a broken harpsichord amid “a flood of blue moonlight” (180). The repeated association between malaria and moonlight in the text draws upon medical ideas from the eighteenth century: “epidemic fevers are caused by some noxious qualities of our atmosphere…such changes as produce those effects may happen in it on all seasons by the influence of the moon” (Mead, 68). Moonlight, as the key metonym for malaria, envelops the text and unmoors it from the sexual and musical ideologies of the Victorian.

<13>The entanglement between haunting and contagion in “A Wicked Voice” crucially draws upon the medical vocabulary of malaria. This medical vocabulary becomes key to the expansion of what is possible in terms of the aesthetics and the politics (of gender), ascribed to the Victorian. Thereby, the text insists on the “firm link between aesthetics and politics” (376) that Chatterjee, Christoff, and Wong point out as the seminal object of “undisciplining” Victorian studies. What lingers within the late-Victorian text “A Wicked Voice” is not merely the specter of the eighteenth-century musical past, but the revenant of malaria that proleptically extends into the present. The historian Rohan Deb Roy in Malarial Subjects has noted that “malaria figured as one of the cultural tropes which emboldened imperial discourse to argue that the colonies were characterised by a temporal lag” (102). In other words, malaria becomes a colonial disease through a rhetoric of belatedness. The border between the healthful imperial center and the malarial periphery is drawn along temporal lines. Even though not explicitly associated with the colonies, Lee’s depiction of malaria in “A Wicked Voice” dents into the temporal frontiers of the normative Victorian. Magnus’s body, “wasted by a strange and deadly disease,” becomes a site of embodying a deviant time, suffused with purportedly aberrant musical and sexual habits, within what is conventionally understood to be the Victorian (181). Lee’s depiction of the untimely queerness of malaria then undoes the secure border between imperial and colonial bodies as well as the temporality of the Victorian Empire that sustains it.