<1>Histories of women’s leisure largely ignore athletic activities available to women before the 1890s. Peter Borsay explains that “the central motifs in women’s leisure have been home and family. Thus practical activities–such as sewing, knitting, embroidery, cooking, and gardening–which support domestic life, and where the line between work and leisure is unclear, have often contained a strong, but concealed recreational element” (116). Borsay concludes that “the extent of female participation in physical sports remains unclear” (121). Yet Victorian periodicals provide a substantial record of opportunities for women’s athletic leisure interests during the second half of the nineteenth century. Activities such as golf, mountain climbing, walking, swimming, ice skating, boating, cycling, rowing, hunting, tennis, and archery attracted women with time and money to pursue them. Roller skating took precedence during the years 1874 to 1877, when it rapidly developed as a fashionable and suitable athletic activity for middle to uper-class women throughout Britain. Hugh Cunningham reminds us that “historically, leisure has been closely linked to class,” and athletic activities such as roller skating required time, equipment, and (especially difficult for women) space (4). Women spearheaded the roller skating movement, although the social and material nature of patriarchal power during nineteenth-century Britain produced a masculine hegemony that dominated ideologic and physical spaces for women; the phenomenon of roller skating during 1874-1877 demonstrates a resistance to traditional gender relations. Rinking addressed longstanding complaints about women’s physical and mental idleness by providing an acceptable way to counter domestic lethargy, and it offered a degree of freedom not experienced in previous forms of active leisure. Skating also took women out of the home into masculine spaces of the gentlemen’s and sports clubs that established the first rinks, enabled women to choose romantic encounters with men of various classes, and put women on public display as physically strong and independent.

<2>Shortly after New Yorker James Plimpton sparked its popularity in Brighton with a four-wheeled, rubber-cushioned roller skate, the author of “Rinkualism” in the World claimed that “there is no town of any pretensions to consideration of fashion, marine or inland, which is without its rink; there is no provincial miss, with a proper sense of what is due to herself, who passes a day without her rinking exercise” (10). Roller skating became so popular that a new language evolved in cultural discourse characterizing the activity of skating on wheels, with words such as rink, rinking, rinkomania, and rinkualism entering common practice. The press reported the latest developments in skates, rinks, rink fashions, and rink gossip. Concrete or asphalt surfaces replaced ice rinks, and private clubs made room for new restaurants, live bands, effusive floral gardens, and special events. According to London Society (July 1875), “Rink, within only the space of one year from this time, has become in Brighton, in Belgravia, in Liverpool, in Bath, Cheltenham, Ryde, and Southampton, among other places, a household word,” as well as a required household expense (64). The comment emphasizes that the monthly budget of one-and-sixpence for the rink must be provided for, in addition to rink fees, skates, clothing, and other expenditures. The rinking habit is taking business away from the shops because everyone is at the rink. The list of financial priorities indicate the status of rinking participants: letting go of photography to make room for the rink is an extravagant choice. However, one must join in with the crowd when “‘To the Rink, Ma’am?’ is the offer of every cabman; and ‘Land to be let for a Skating Rink,’ ‘Rink Waltzes,’ and ‘Rink Costumes,’ are among the daily advertisements which show how readily inventive mortals learn to set their mills to every stream which promises to turn them” (64). The growing obsession for rinking was good for business, as demonstrated in continuing weekly advertisements from clothing merchants and large investments by rink proprietors in promoting new rinks.

<3>Victorian periodicals quickly began the work of commodifying women’s fashions, women’s femininity, women’s courtship rituals, and demand for news of the latest in rinking. Class periodicals such as the The Queen and Ladies Newspaper offered readers advice and instruction on how to skate, what to wear to the rink, locations of new rinks (and the amenities offered there), where to go for the best social opportunities, and gossip about who was there. The author of “Roller Skating,” published on January 1, 1876, promotes skating as a new, “health giving” activity with advantages like “no other pastime in which ladies indulge”; skating on wheels marks a “new era” for Englishwomen (“Roller Skating” 12). Previously confined by exercise that was “simply a painful duty to be gone through,” women could now participate in a fun activity that was also healthy: “Self-propulsion is fascinating in every form, but the delight of roller skating is not confined to that alone. By its means the sickly become strong, weak ankles and stooping gait disappear, and an immense amount of really hard exercise is taken without any feeling of weariness, because the mind is fascinating while the body is working” (12). The author discusses proper skating techniques and offers two golden rules: “First, that the foot that falls to the rear at the end of each glide is the propelling power for the next glide. Secondly that the nearer the feet are together, the easier it is to utilize this propelling power” (12). A diagram of right and wrong ways to skate accompanies the feature. The author insists that readers needn’t worry about weak ankles, because the roller skate does not strain ankles like ice skates will do. She encourages the potential skater by offering a moral justification for getting out of the house and onto the rink: “Every one should strive daily to learn something new or perfect something old, as it is the feeling of advancement towards perfection, no matter how far distant or hopeless an imaginative state of perfection may seem, that gives such a charm to any pursuit requiring for its full attainment perseverance, energy, and skill” (12). Other articles in the Queen provide readers with practical information about fees, membership requirements, and descriptions of rinks.

<4>New rinking fashions boosted profits for dressmakers and clothing businesses, which then supplied women’s periodicals with advertising. Merchants such as Ulster House created and widely advertised special hats and jackets designed for roller skating. An Ulster advert in the World on November 18, 1874 asks “lady customers” who “put in an appearance in the shooting-field or skating-rink, or indulge in rough country walks” to consider purchasing the new shooting or skating suit in homespun and tweed” (“Advertisement” 23). Ulster quotes the Queen in every ad as a recommendation to his products, demonstrating the influence of women’s periodicals in trendsetting skating fashions. A later issue of the Queen (December 11, 1875) advises women on what skaters are wearing at the Brighton rink: “Dark dresses of every colour (but plum, brown, blue, and chocolate seem the favourites), look like riding habits, so severely simple are they, seem much in vogue; no trimming, but small buttons close together on front of jacket. They accord well with the high, narrow-brimmed hats commonly called ‘deerstalking.’” (“Rinking Costumes at Brighton” 400). The deerstalking hat was like the double, side-brimmed variety commonly worn by Sherlock Holmes in popular illustrations. Ironically, this Queen columnist advises against wearing the “barbarous Ulster coats” advertised in many London newspapers. Women should get rid of excessive petticoats and large hats, wear flat boots, and, above all, leave the hand muffs at home because they restrict use of the hands, vitally needed for defense if the face is heading down toward the rink’s concrete or asphalt surface.

<5>The rigorous activity of skating required modifications in fashion for safety as well as comfort. Advice from women’s periodicals shows the influence of the practical dress movement that parallels increasing freedom from gender restrictions evident from the 1870s to the end of the century. An author in the World urges women to “adopt loose, short, neatly looped-up dresses of some soft material that will hang in artistic natural folds and not impede their motions”; otherwise they will “resemble waddling ducks instead of gliding girls” (“Falling Ladies” 20). For best comfort, “above all let them abandon their present arrangement of tiers of petticoats, some not intended to show, some showing too much, and all of a stamp and style utterly unsuited to the purpose” (20). J. A. Harwood, author of a new roller skating guide titled Rinks and Rollers (1876) discusses the importance of simple dress: “Fine raiment should be avoided, as it lends an additional terror to falling; but a short, plain stuff skirt for ladies. The jacket should be left in the cloak room. The hair done up in a knot at the back of the head, as a precautionary measure. The hands enclosed in gloves, not too new. The feet encased in lace-up boots, fitting well and firmly with a large, low heel . . . Don’t lace yourself up tightly” (84). Concerns for respectability and reputability continue to dictate new fashions, but leisure activities such as roller skating allowed women to unlace their bodies.

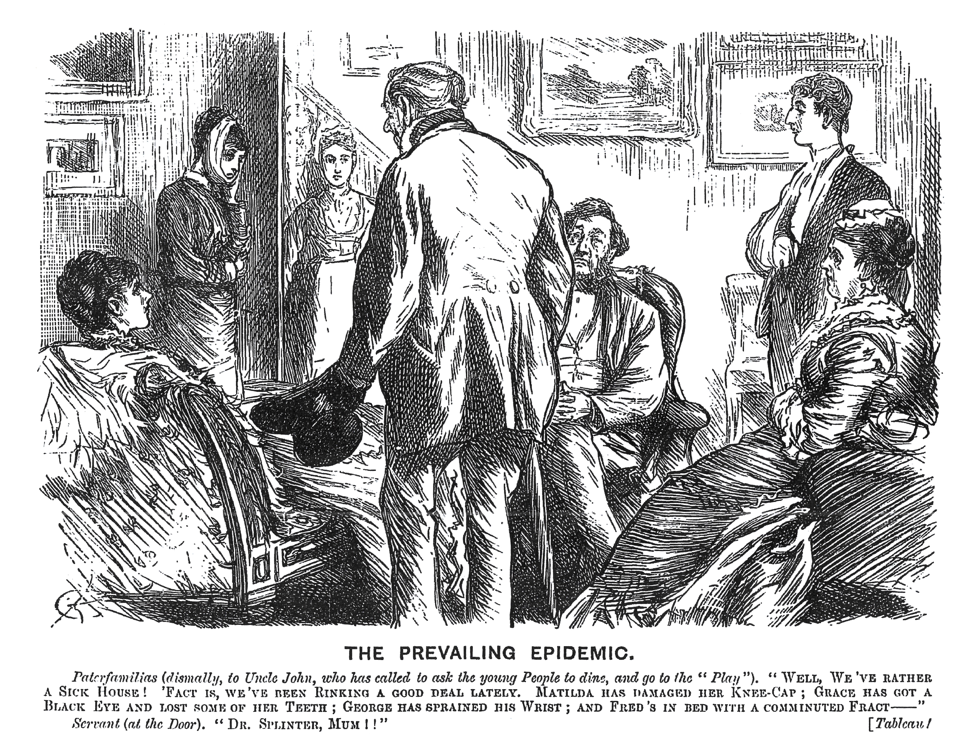

<6>Warnings about the dangers of roller skating appear in periodicals as soon as the skating mania began. In spite of the thrill of an invigorating trip around the rink, roller skating can be extremely dangerous, and many features in Victorian periodicals caution women against breaking elbows, wrists, arms, legs, backs, noses, and teeth. Harwood calls the naysayers “rink-assailants” who tell alarmist stories of “catching cold and dying in consequence, of others maimed and injured for life by the asphaltic folly”; Harwood reasons that nothing is completely safe in any sport, and accidents do happen, but they are rarely serious (10). For a young woman partly dependent upon her looks for social advancement, broken bones and teeth would be reason enough for avoiding the activity. Added to the personal pain would be expensive replacement of torn clothing and possible doctor bills. However, Harwood claims that the only serious injuries occur are when older women decide to skate for the first time, or when ladies keep their hands in their muffs instead of having them free. All else is “asphaltomania” (11). In figure 1 (March 11, 1876) Punch offers a comical depiction of an entire family who is housebound because of skating injuries, constituting an “epidemic” of damaged knees, black eyes, broken teeth, bone fractures, and other injuries that prevent the family from going to dinner and the theatre with Uncle John. They must stay home with Dr. Splinter instead. The illustration’s title, “The Prevailing Epidemic,” indicates that roller skating is a highly contagious disease that is rapidly spreading throughout the land, with dire consequences.

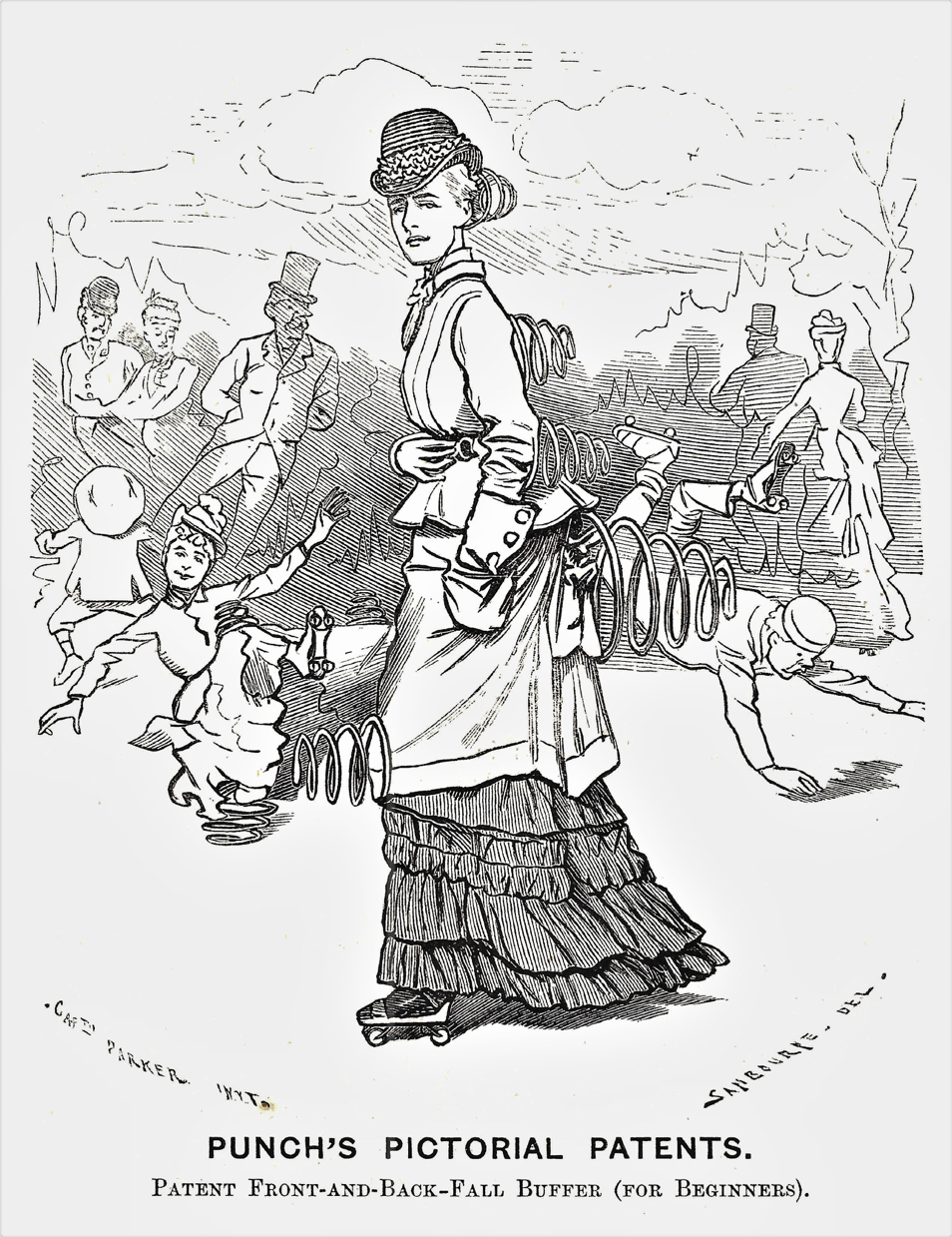

The following month Punch provides a safeguard that will at least keep Dr. Splinter away (fig. 2). In “Punch’s Pictorial Patents,” artist Linley Sambourne proposes “front-and-back-fall” springs that will keep a woman skater upright, so to avoid injuries like the ones bound to occur in the skaters crashing behind her.

<7>Proper training would help a woman stay upright on her skates, while building adequate strength and skill to display her body in elegant form. However, women often took lessons from skating masters because they wanted to improve their performance in the art of skating as a hobby; Harwood asserts that there should be no reason women cannot be first-rate skaters, which results in “forming a succession of well-defined and elegant curves without rapidity or shuffling of the feet, and with a concealment of all exertion or effort” (83). Proficient skaters produce graceful motions, which recommends women as better skaters than men, since “Ladies are naturally more graceful than men” (83). The assumption may be appropriate in light of traditional views of femininity, but Harwood destabilizes gender definitions by asserting that women are “naturally more successful in concealing their emotions,” which allows them to skate better (83). Thus she questions the practice of taking instruction from men on skating and concludes that men are jealous of women because they are better skaters: “jealous man, intent always on ‘the subjection of women,’ takes their instruction upon him, and drags them about with crossed hands to destroy all feeling of independence” (83). Here Harwood points to the prevalence of men who insist on skating in pairs, which she finds oppressive. Some articles agree with Harwood about the limitations of skating in pairs because it is unsafe: if one person falls, the other follows. The practice also restricts a woman’s freedom to enjoy the movement of her own skating. In Harwood’s view, skating is an activity that women can do without men; “let them reject his services” and “begin their early struggles without other assistance than the one occasional hand of a friend” (83-84). Her comment emphasizes the new opportunities for female bonding introduced by roller skating.

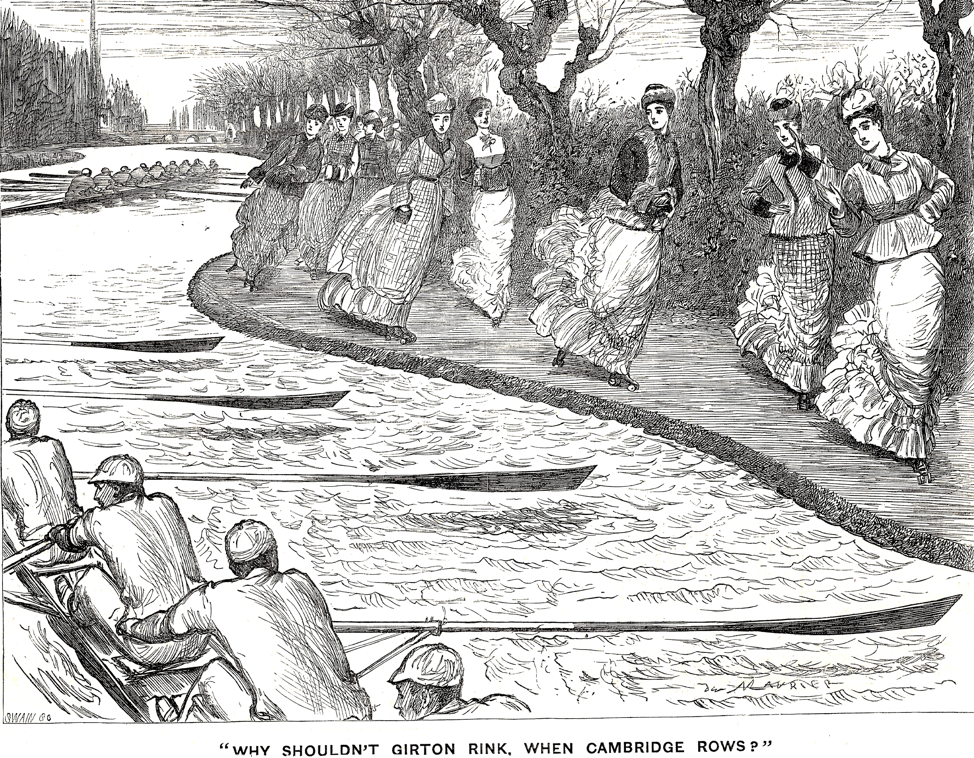

<8>Skating was a courting ritual for some women, as indicated in the Punch illustration in figure 3. One observer in London Society reports that “A young lady admitted to a bosom friend that this skating in couples was far more pleasant as an exercise than any waltzing; ‘and then, you know, you have a partner all to yourself, just as nice’” (68). However, the dominating position of the men over their skating partners in figure 3 validates Harwood’s complaint about skating in pairs. The two dogs leading the pack provide an additional suggestion of sexual pursuit. Undoubtedly, many women participated in the roller skating fad as a social ritual to attract men. Private skating clubs provided class-specific opportunities for socializing with suitable marriage candidates. Rinking soon took the place of croquet in bringing people together, without the problems of weather or dependence on the skill of others for its success. An author in the Queen comments that croquet is “often a mere excuse for dawdling about; skating on the rink involves exercise of a beneficial kind” (“Rinking” 93). Romantic poems, short fiction, and novels began to reflect current interest in skating as a courting activity. An author in Once a Week writes that “It would seem as though the power of moving about gracefully and safely upon wheels would soon be as necessary an accomplishment for the young lady who meditates ‘coming out’ as is the knack of the last new waltz or the art of the old cotillion’ (“Skating on Wheels” 252).

<9>Part of rinking’s appeal for women was in its compliance with traditional expectations for femininity: the graceful, flowing movements of skating displayed women’s bodies in elegant form. An author in Belgravia claims that “Nothing sets off the female form like skating . . . A lady perfect, and sailing along on graceful semicircles right and left on the ‘outside edge, is seen to more advantage than she can appear in any other possible position” (147). As Henderson, et al. note: “Any activity that emphasized beauty and aesthetic appeal was most in keeping with the transcendent female image, and was more acceptable from the viewpoint of society” (36). The comment invokes notions of women in performance, on display for the male gaze. In focusing on developing proper form that will ultimately improve a woman’s deportment and social acceptance, skating is a cultural act that confirms the dominance of men because the objective is purportedly to please men; however women participate in voyeurism with men as well as with other women, thus complicating the stability of patriarchal relations.

<10>The pinnacle of exclusive places for “smart people” was Prince’s in Belgravia, a private rinking club with a subscription of five guineas a year (“What the World Says,” December 16, 1874, 14). Prince’s rink was located adjacent to the cricket grounds beside a tree-lined row of umbrella tents, where people could rest, talk to people, have five o’clock tea, and watch the skaters. It also had a covered skating hall 120 feet long by 70 feet wide, with a vaulted roof and an attractive ambiance provided by pendant star gas-jets around a rink decorated with flags and shields. Atlas reports that at Prince’s, “there is seldom an afternoon when less than two hundred people are to be seen” (14). The popular skating club is described in London Society as being “like an oasis in the desert; you step aside from the turmoil and the monotony of Rotten Row—Elysium, perhaps, to country cousins; you escape from all the glare and grinding of the streets, and find yourself in a kind of fairy bower, where the bal aux patinées is enacted daily under green trees on one side of a beautiful cricket field” (“Skating Rinks” 68). It was so popular that many fewer women attended the Regatta Week at Cowes in 1874, according to the World (August 12, 1874). Skating at Prince’s ensured class-conscious mothers and young women that they would not encounter riff-raff, which might include anyone beneath a desired middle-class social level. Roller skating often served as a mean of maintaining or acquiring status, although some skating rinks built for commercial purposes did not restrict membership according to social boundaries guarded by reputability. Membership for young women at Prince’s was limited to those who had been presented at Court, and one observer noted that presentation at Court now meant a desire to qualify for Prince’s. Having a daughter that skated at Prince’s opened doors to other social events. A feature article on Prince’s published in Belgravia provides a comforting assurance to its readers that “the Court is made a kind of social sieve to separate the grain from the chaff of society, and perhaps to eliminate Anonymas” (“Prince’s and the Skating Rinks” 146). Soon the Lord Chamberlain would announce that no one could be presented at Court who was not a member at Prince’s, according to Belgravia (146).

<11>However, the restriction evidently did not protect society women from male “chaff,” for Atlas comments that “Ladies of the very bluest blood intrigue for a turn with the Professor, and demoiselles born in the purple are glad to get a passing assistance from ‘Jack’” (December 16, 1874, 14). His sardonic observations typically contain a gossipy effect, and here Atlas suggests that women are more than willing to reach out to any man for instruction, assistance, or a turn around the rink, regardless of his social status or reputation. The notion of such behavior implies a careless disregard for propriety, and his comment might touch a nerve with middle-class readers who “resisted the spread of sport ‘down the social ladder’ for fear of working-class domination, with its consequent immoral possibilities,” as noted by Huggins and Mangan. Further implications of impropriety are evident in Atlas’s passing comment that “The latest sensation at Princes is the borrowing at night of the lanterns of the workmen enlarging the rink, and skating about in coupled affinities in secluded parts” (“What the World Says,” November 11, 1874 13). Harwood complains moralists are calling for the “flirtation-ground” at Prince’s to be shut down, but she discounts them as people who have been black-balled or couldn’t qualify for the club, so they think others shouldn’t go, either. Harwood’s more liberal explanation is that rinks give young girls opportunities to choose their own husbands; if the parents would only listen to their daughters, they would hear that: “if they prefer to be less rich and more happy it is their business; that they cannot form an accurate judgment of a man by dancing with him twice at two balls; that they can do so better by meeting him daily at the rink under sometimes rather trying circumstances; that they are able to converse there more freely than in the crush-room at the Opera, at a dinner party, or even in the Park” (19). Harwood concludes that rinking occurs in a public place, and it is no more dangerous than any other public place. Harwood admits that inappropriate conversations and acquaintances are possible between “unauthorized forbidden friends and lovers” anywhere, but justifies that rinks allow young people to meet “in a way in which they meet nowhere else—I do not mean in collision” (17). Anyone from swells to skating masters could be suspect because of the unpredictability of private encounters and rink admissions policies at uncrowded or off-times during the week. Some women traveled to Brighton for lessons from the best teachers of elegance, so they would have the better chances with men at Prince’s. The urge to impress men was natural for young women of marriageable age, but skating rinks immediately became a moral concern for some, and a gender threat to others. Roller skating allowed women to invade masculine spaces, because skating rinks such as Prince’s were often built as additions to gentlemen’s clubs and areas traditionally used for men’s sports.

<12> Punch cartoons frequently satirize women as mannish pursuers who threaten the social fabric with indecent sexual encounters. Mike Huggins writes that Punch cartoons “were used to present their view of women’s social place, to reinforce traditional gender ideas and maintain prevailing ideologies. Their male fears meant that sporting women were consistently denigrated” (137). The recurrence of such images also confirms the power of skating to free women from social constraints, and reactionary fears implied in the images respond to the reality of their encroachment into masculine spaces. The Punch images reflect opportunities provided by roller skating, not for indecent or indiscriminate sexual behavior, but for equality. In the Punch illustration in figure 4, women skating on the banks of the River Cam confront a group of Cambridge rowers. Although the groups are moving in the same direction, the rowing men are looking backward while the women skate forward; their positions suggest oppositional gender relations, and the homosocial bonding of male and female units articulates a face-off competition between the sexes. The women are not skating arm-in-arm, as in a romantic outing; each is independently and freely moving, while the men are bound to the oars by their activity. The two women leading the group, their free arms akimbo, seem to be somewhat taunting as they wave at the rowing Cambridge men. One message of this Punch image is that women are challenging men in sports, and the encounter positions women above the men in a dominant position. The women are not roller skating to pursue men, they are not skating in pairs, and their sexuality is not on display at a skating rink. Instead, the activity is an example of female bonding: they seem content with sharing leisure time with other women. However, Huggins contends that “In the 1860s and 1870s women were only playing at playing games constrained by costume and custom, but by the 1880s sporting women and ‘new women’ in general were seeking more liberty and more strenuous games” (139). The female advantage suggested in figure 4 is a precursor to future freedoms, but the men have institutionalized, special clothing to support their activity, while women are still restricted by layers of petticoats and dresses that tie back at the knee where flexibility is most needed. Yet the question “Why Shouldn’t Girton Rink, When Cambridge Rows?” is answered by the women skaters: as students of Girton, the first women’s college in Cambridge, they are already participating in education, as well as athletic sports.

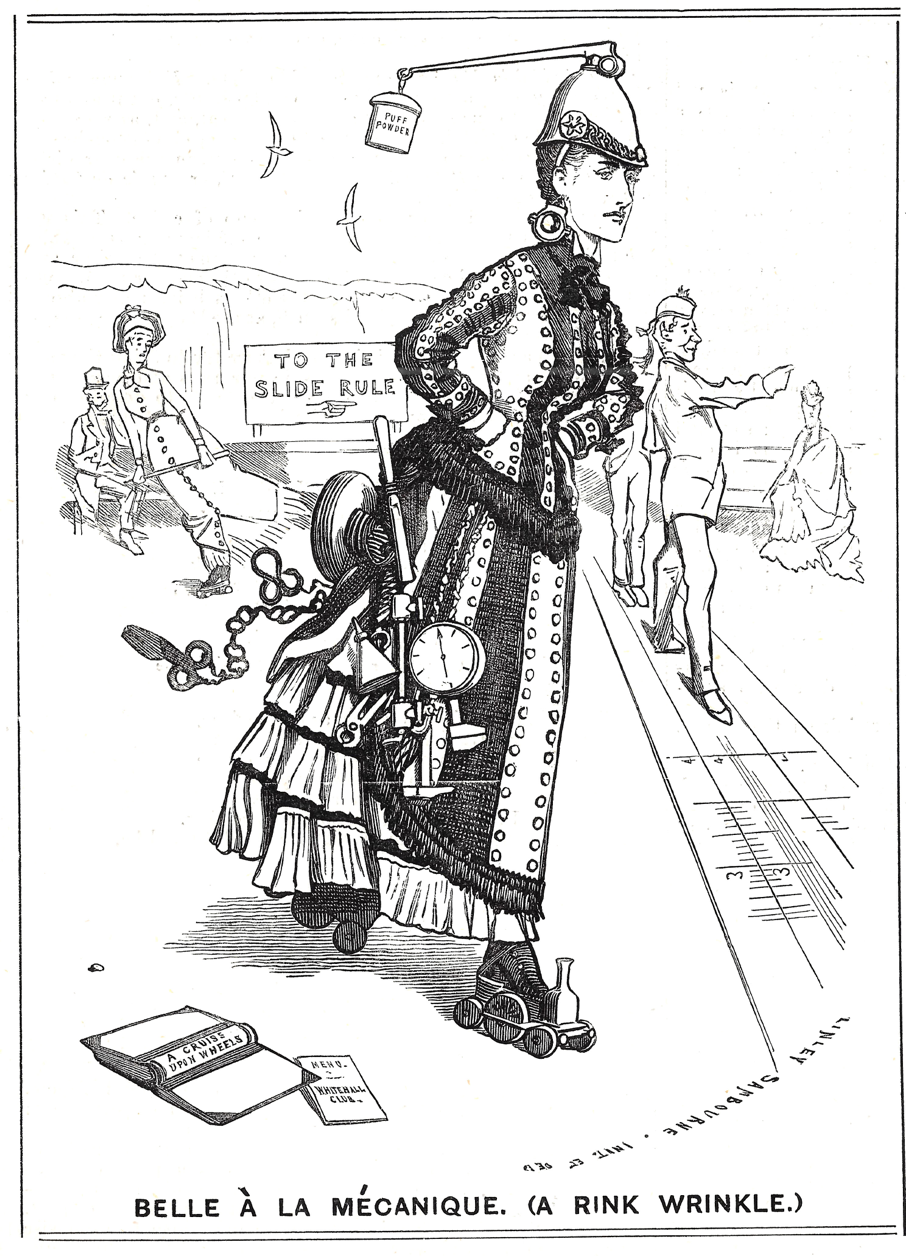

<13>As industrialization inspired the creation of new spaces for forming economic and political networks for men, women used cultural leisure space to resist male domination and challenged a masculine sphere weakened in the 1860s by the invasion of women in higher education and professional life. Linley Sambourne’s Punch image in figure 5 (October 16, 1875) taps into the roller skating fad to articulate fears of women entering male-dominated professions. “Belle à la Mécanique. (A Rink Wrinkle)” displays a skating woman profusely decorated with tools of engineers. Her face is determinedly serious as she skates on models of railway cars. The book at her feet, A Cruise upon Wheels, is a comical travel book published in 1862 by Pre-Raphaelite writer, illustrator, painter, and brother to novelist Wilkie Collins, Charles Allston Collins. The story is about two comic characters, Mr. Fudge and Mr. Pinchbold, who take a cruise through France in a crowded, one-person carriage pulled by a tired horse named Blinkers. By associating the skating woman with misadventures of nincompoops, Collins degrades the seriousness of purpose reflected in the woman’s leisure activity. The Whitehall Club menu beside Collins’s book is a reference to recent growth of engineering professions that inspired the construction of the Whitehall Club in 1866. The implication is that the skating “Belle” is like a woman invading a gentlemen’s club that accepts only leading engineers and men with official government business at Whitehall.

<14>Women’s involvement in roller skating often threatened men because the rink-building began as an investment by gentlemen’s clubs and sports clubs, a traditionally gendered enclave of masculinity. Although memberships for women restricted them to the rink, the notion of women becoming members of the club seemed invasive to some misogynists who wished to escape feminine influence. One author complains that women will not leave men alone “for one brief hour of the twenty-four” (20). His article in the World published during the roller skating fad (January 5, 1876) indicates that women are invading male terrain: “Formerly girls met young men at balls and parties, or, when riding in the Park, always under proper surveillance and chaperonage; now from early dawn they are in each other’s company, skating unchaperoned in the morning, riding attended only by a groom, and joined by any favoured cavaliers, and entertaining the same men at confidential kettledrum tea; or, if in the country, are walking with the guns, rowing in the boats, or riding to the hounds” (“Leave Us Alone!” 19-20). The author wants women to remain at home or in the traditional spaces designated for courting, and he claims that the invasion of women into men’s spaces threatens civilization. The trend is not because men have softened, but because women “have been coarsened and emboldened to a pitch that forms a sad subject of contemplation to a thoughtful mind” (19). The World was a weekly society paper begun and edited by Edmund Yates, a man known for shrewd satire; thus it is possible the article is meant to be too ridiculous to be taken seriously. If so, the punch line occurs in the juxtaposition of the article with an advert for a new skating rink to be built by The Bayswater Club and Skating Rink Company, Limited.

<15>Some critics felt that women’s roller skating would deteriorate civilization: “‘Asphalte, asphalte everywhere, and naught to do but rink.’ Rinkualism is revolutionizing English society as completely and as rapidly as ritualism ever threatened to revolutionise the English Church. It is deeply affecting our welfare, mental, moral, and physical; it is influencing our commerce and trade; it is accomplishing a gradual transformation in the appearance of our pleasant places” (“Rinkualism” 10). Middle-class periodicals frequently published articles expressing concerns that women’s increased freedoms with roller skating was dangerous to society. One critic complains that daughters have too much independence and are mixing with frivolous people at the rinks: “The skating mania has produced a pitch of independence positively unknown before in the annals of society . . . The girls are away from their mother’s side for hours at a time: as they never have time to read a book or to give a thought to any subject but dress, the friends they select are naturally as frivolous as themselves” (“The Sting of Truth” 10). Another warns that, so long as English mothers “allow their daughters to frequent resorts-whether undesirable watering-places or even more undesirable skating-rinks—where all that is coarse and vulgar in mankind comes to the front as naturally as scum rises to the water, they are doing their best to secure for the husbands and children of the future mothers who will make the name of home the symbol not of a blessing but a curse” (“The Deterioration of Society” 3). Yet another warning appears in the Sporting Gazette, where an author proclaims that the introduction of rinking is “a distinct blow to that domesticity which used to be the ideal of English life. The excitement of mixing every day with a crowd of strangers, of taking the daily exercise in public surrounded by onlookers, must have an unhealthy effect” (“Rinks and Rinking” 317). According to this report, young women will become bored with home life and unsatisfied with less exciting routines of the traditional English home. Such a complaint in a magazine that should support sporting activities emphasizes the threat women presented for male sports enthusiasts. Women shouldn’t be competing with men anywhere, whether on the rink or in the field. Fortunately, Huggins and Mangan note, “the ‘spin’ of the decent was unrelenting, [but] the success of the ‘spin’ was uncertain” (xi).