<1>In the midst of this pandemic, I shifted contingent roles. My year spent commuting out-of-state to serve as Visiting Assistant Professor of English at a selective liberal arts college concluded in May 2020 with the dull whimper of parting goodbyes waved from tiny Zoom boxes. Then, at summer’s end, I landed a postdoctoral position at a research university with only ten days left until the start of term.

<2>Swiftly adapting lessons gleaned from Spring 2020, I planned deliveries for two formats that would be pedagogically new to me. One course was to be taught remotely from start to finish; students could join from an on-campus classroom or from their own computers. They all opted to attend virtually. The two others would be asynchronous classes run exclusively online via Canvas. In the final days of Summer 2020, I navigated this new-to-me learning management system (LMS) while juggling full-time care responsibilities and hours-long orientation meetings. Intellectually, I made the transition from discussion-based seminars in nineteenth-century literature and gender studies for students invested in humanistic inquiry to first-year writing courses geared for students planning their future engineering and business professions. Physically, I transitioned from the living room to the office.

<3>Teaching to transgress—from home—over the past year has required replicating, then crafting from scratch, the collective alchemy of a face-to-face classroom. In that shared in-person space, my students and I would segue from open-ended conversations to chats in small cohorts to individual reflection exercises and back again with ease. I depended on that communal networking for knowledge production. But I struggled to envision how students—now spread from Boston to Tokyo—would feel that same degree of connection and engagement with each other, and with me, through a mediating screen. As bell hooks writes, “our capacity to generate excitement [in the classroom] is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence” (8). Now, sometimes all we had were voices. When students turn off their cameras, how can educators enable their learners’ fullest presence? When students reside across the globe from one another rather than across the hall, how does authentic community form?

<4>In this new world, my working schedule fluctuated around a young child’s sleep patterns while my students orchestrated their class attendance around thirteen-hour time differences, family obligations and illnesses, and mounting fear and burnout. Come September 2020, I met a new group of students for the first time through my laptop screen. Some I would never “see” at all. And even though course evaluations later confirmed that my “passion,” “enthusiasm,” and “energy to teach” bolstered my students at our ungodly starting hour of 8:00 a.m. EST (or, 1:00 p.m. in the afternoon in Ghana; or, 9:00 p.m. at night in China), I was always unsure how well they were coping individually, especially when some only spoke via their keyboards.

<5>I knew that I could no longer count on the same collective energy that had buoyed my other classes through the emergency remote situation in the Spring. I knew that new strategies would be necessary. I also knew that, like many educators, I had neither the time nor bandwidth to reinvent myself.

<6>So, in Fall 2020, I turned to tools that had sustained my connections with students in March and April. I prioritized frequent communication, sending collective emails early and often, soliciting periodic feedback via web-based surveys, and offering one-on-one contact via chat apps and videoconferencing. I incorporated breakout rooms into weekly Zoom sessions and presented documents via screen-share. As the semester continued, though, I experimented with tools that had been, until then, unfamiliar. I built course websites via Wix, created screencast videos via Screencast-o-matic and Canvas’s Studio, coordinated social annotating via Perusall, converted lesson plans into slide decks via Google Slides, and commented on documents in real time while students wrote collaboratively in Google Docs. I composed weekly letters to my students in which I knitted material from one week to the next, signing off from these letters with a humorous GIF to extend my teaching persona across the Wi-Fi void.(1)

<7>Dabbling with such tools enabled me to embrace a transitional, even destabilized, position on par with the one my students occupied: we were all adjusting to new frameworks and floundering, at times, with new technologies. Keenly aware of this increased cognitive load, I relaxed expectations of myself as well as my students. We learned—and continue to learn—how to co-exist in this digital realm together.

Community through Continuity: Using Slack and Google Slides in Spring 2020

<8>Back in March 2020, when most schools abruptly shifted to remote learning, I strove for continuity. I decided to rely only on platforms and practices with which my students had been made familiar during the first half of our semester. For example, one of my three classes, an intermediate-level seminar on women writers, repurposed two elements we had been using since January: Slack and Google Slides. In the free version of Slack, available by web browser or smartphone app, students can communicate through dedicated chat “channels” and sub-channel “threads” set for various topics, as well as through direct messages and private groups. Google Slides is a free resource with a Gmail account that allows students to create presentations individually or as groups, collaborating in real time as the slides save automatically. Students were in the habit of posting once per week to our shared workspace on Slack, a strategy that I had originally chosen for a face-to-face course in order to stimulate conversations outside of our regularly structured class time. I wanted to allow students to spark ideas when their readings were freshest and to make space for students who might feel less comfortable contributing during a faster-paced in-person conversation. In class meetings, I brought attention to students’ Slack comments by discussing how their remarks related to a set of textual quotations that I projected on a large screen in the classroom as Google Slides—quotations that I had selected based on the students’ collective interests in the chat forum.

<9>During that first half of the semester, however, Slack did not become the animated space I was hoping it would. Students tended to post one remark without returning to engage their peers in a back-and-forth dialogue, making the channels no less static than a conventional LMS discussion board. I did, on the other hand, find that Google Slides enhanced our conversational fluidity, not only because the quotations and images derived naturally from students’ online comments, but also because the projections focused our shared visual attention in the room. Starting in March, though, both applications became a lifeline.

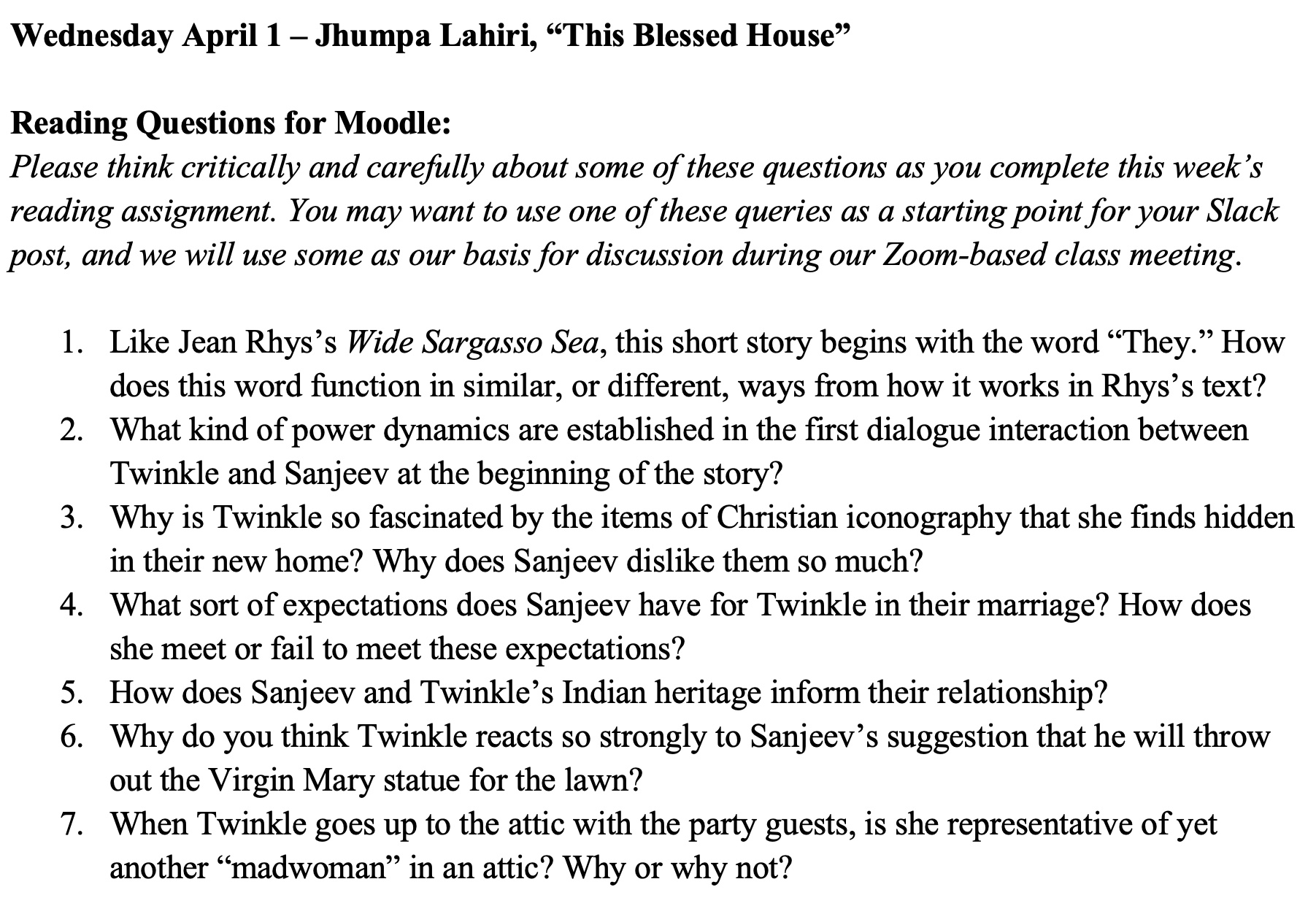

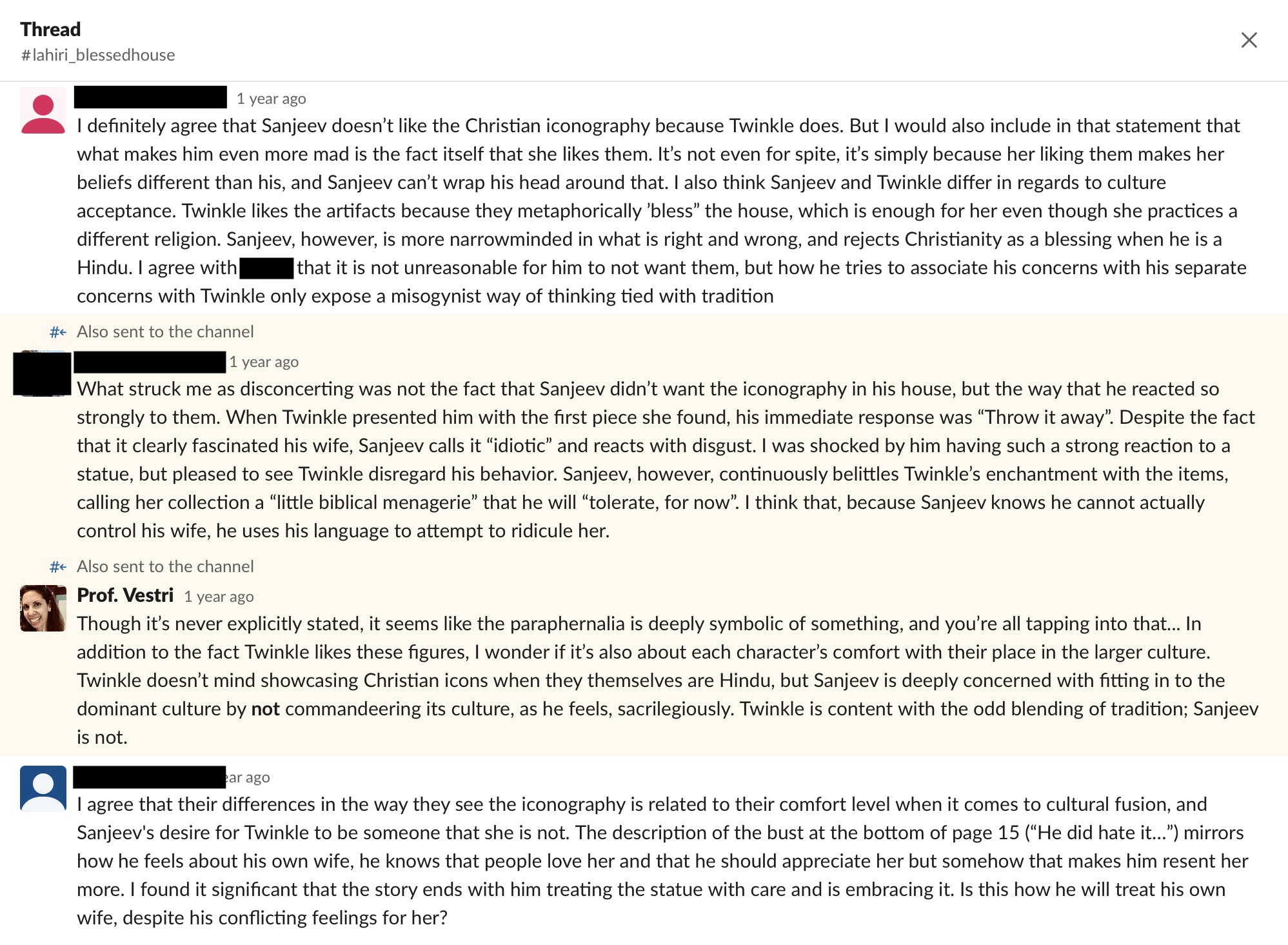

<10>Since the class was already adept at navigating these tools, I repurposed Slack and Google Slides for our remote classroom, enabling us to continue our collaborative work asynchronously through Slack and synchronously through Zoom. To accommodate my students, who had been unexpectedly upended from their on-campus residences over spring break with no opportunity to collect their belongings, as well as my own increased demands at home, I cut our weekly meeting time down from the prior in-person 150 minutes to just one 45-minute session. Each weekend, I provided reading questions via our LMS (see Fig. 1) and asked students to post one thoughtful hundred-word comment to Slack in response (see Fig. 2; previously, there had been no directive prompts).

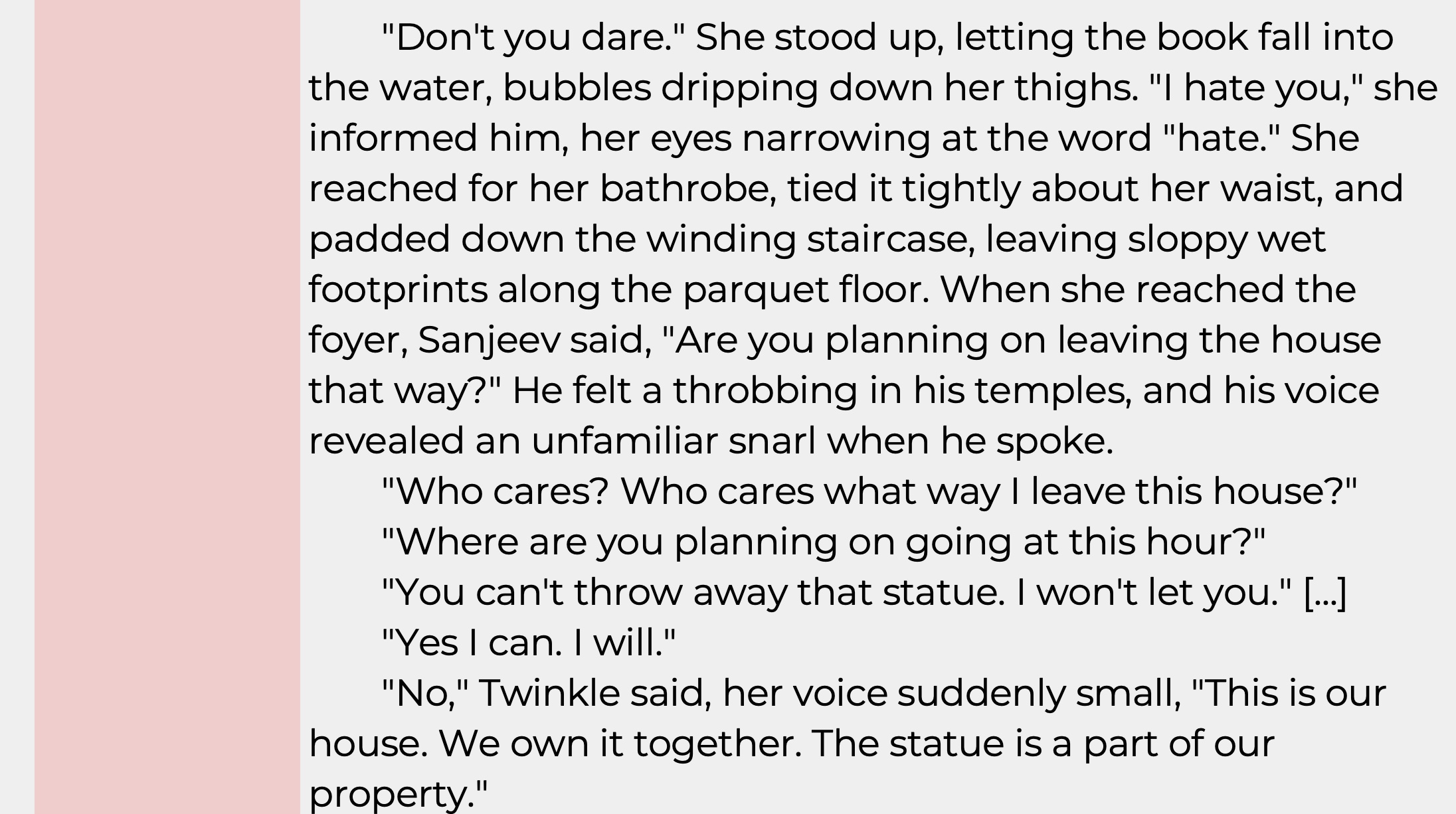

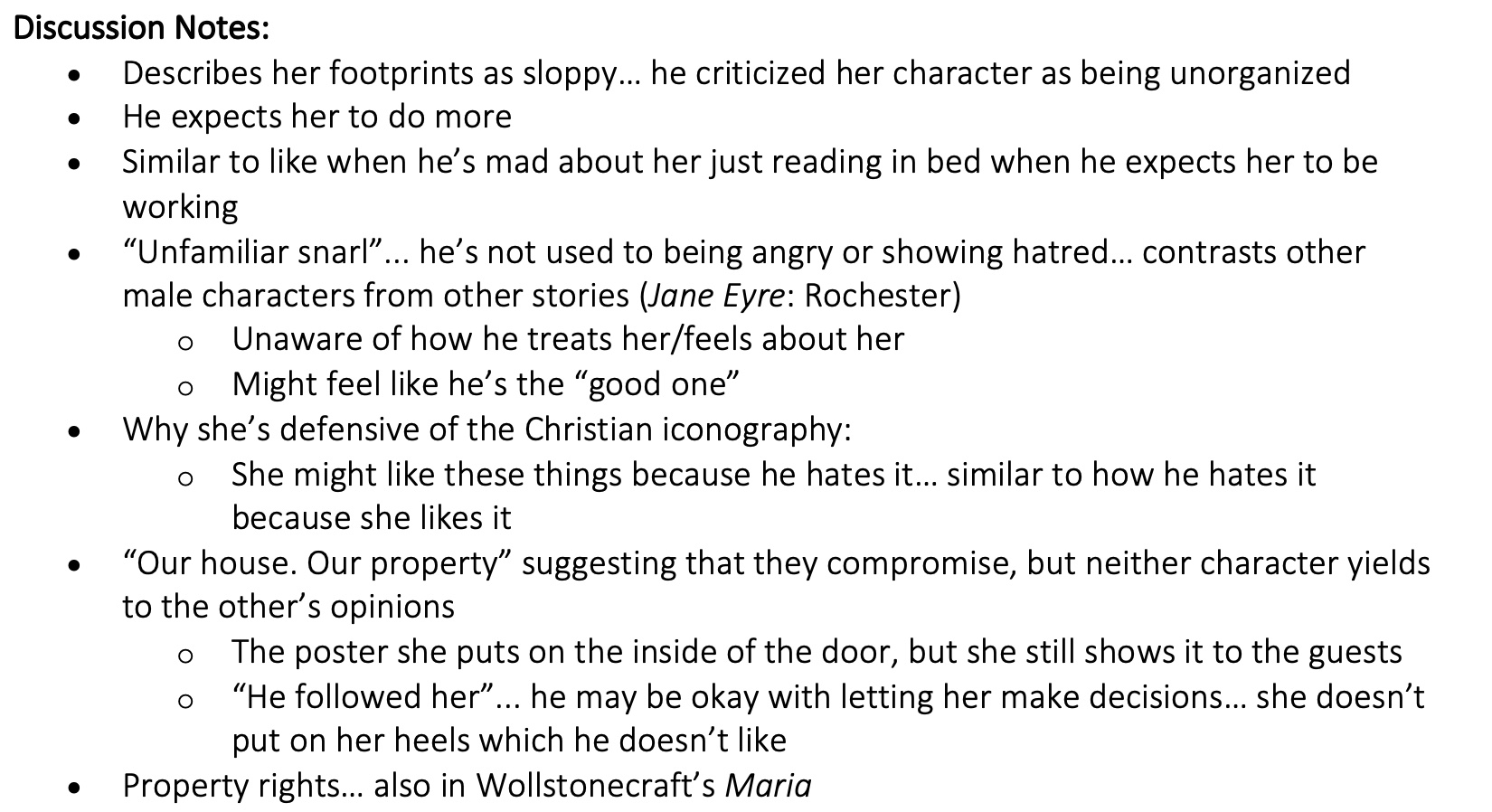

<11>Then, on the day before our synchronous class meeting, I would share a deck containing three or four textual slides with quoted passages driven by students’ interests as mentioned in the Slack chat—a chat that had, indeed, now become more of a reciprocal conversation since students were motivated to connect virtually from their disparate locations (see Fig. 3). We began each Zoom session in breakout rooms in order to foreground as much “face” time as possible—and to provide me the ten-minute interval I required to whisk my young toddler off to naptime. Each small group examined one passage together, the groups took notes, and I later posted all notes on Moodle to share with the entire class (see Fig. 4). Following these initial fifteen or twenty minutes of discussion in breakout rooms, we returned to the main room to interact as a whole using Zoom’s gallery view. I favored not using screen-share to display the slides again during this portion, since I wanted to connect with my students as much as possible and facilitate their connections with one another without extra visual distractions.

<12>By reducing cognitive load, providing multifaceted assistance, and prioritizing student connections in each remote session, this class, as well as others, emphasized the value of community to support us through a traumatic time. To my delight, students showed up ready and willing each week, both asynchronously and on camera.

From Continuity to Connectivity: Using Slideshows in Fall 2020

<13>While these methods were successful in extending an established seminar’s collaborative energy into the virtual world, a few months later I stumbled into a brand-new teaching environment: I would be leading three courses, one meeting remotely and two working asynchronously online, at an institution that was brand new to me, with students who were brand new to college. I no longer had the advantage of continuity. Some students would be at home, some on campus, some abroad; some would be on Zoom, some on Canvas. The mood had changed. In a synchronous first-year writing course with only twelve students, for instance, I found myself falling into an unfamiliar habit of one-way delivery, lecturing to students more than I ever would do in a face-to-face course. The struggle to stimulate dialogue with this new cohort was straining given students’ lack of familiarity with seminar-style discussions, complicated by the awkwardness of “un-muting” in a videoconference setting, with its odd pauses that tend to instill silence rather than invite input. Genuine conversation was hard to come by. I turned, once again, to slides.

<14>Developing effective slideshows in this context demanded new strategies than the ones I had honed in Spring 2020. As I increasingly embraced this tool, I began to balance teacher-centered delivery with student-centered active learning. To do so, I punctuated synchronous slide-led lessons with designated time for individual reflection, directed exercises, group work, collaborative writing, and other interactive modes, alternating between approaches every ten to fifteen minutes to ensure variety and maximize attention (both theirs and mine). During each synchronous hour, I assigned students multiple tasks that would give them anywhere from two to twenty minutes to turn off their cameras and work on their own or to gather in small groups without me present. This variety reduced the feeling that either the slides (or I) dominated.

<15>For example, I recently held two consecutive class sessions about engaging the opinions of other writers. Outside class, students had been researching conversations within their communities, a strategy I chose this year so that our course “content” would derive from students’ backgrounds, experiences, and identities. This choice not only allowed us to learn about one another and engage diverse perspectives, but it also minimized intellectual burdens during a continuously strenuous time. As students researched journalistic opinion pieces outside of class, we worked on understanding the genre during our synchronous meetings. To help students comprehend the structure of op-eds, I developed a slideshow informed by short readings from Cathy Birkenstein and Gerald Graff’s They Say / I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing (2014, third edition; since I was no longer traveling across state lines to reach my on-campus office, I had to rely on older editions of texts that I had available as scanned PDFs on my home computer). To facilitate virtual engagement, the deck alternated between information-delivery and practice exercises in order to show students how op-eds position arguments in the context of other voices. Instead of serving merely as a backdrop for an instructor’s content-dump, the slides became a conduit for interaction, prompting students to pause and apply lessons in peer dialogue or independent activities. Surprisingly, instead of compelling me to speak at students, slide decks are helping me to work with them.

<16>In this particular session, I first incorporated four slides that presented other writers making “they say / I say” moves (see Fig. 5 for one example). With images captured via screenshots, I showed sentences from op-eds that the students had recently read as a model of the genre, where one writer quotes or paraphrases from another. These sample images alternated with text-only slides reinforcing what I explained verbally. Using the “animate” feature in Google Slides, I set the presentation mode to reveal one bullet point at a time, so that the written words acted as shorthand for what I was saying “live” (see Fig. 6 for example of full slide). The bullets did double duty: they also acted as notes for me so that I could tune my attention on my students—whom I see in a compressed gallery view on screen in front of the slides—rather than read from offline notes or other on-screen windows. This semester, I have also been making an effort to speak into my webcam’s “on” light, as odd as that feels, so that it appears to students as if I am looking directly at them. Slides allow me to do this more seamlessly.

<17>After I presented this introductory material, I paused for students to practice. The next slide, a barebones instructional one (see Fig. 7), invited them to locate “they say” rhetoric in an op-ed they had each researched and to reflect on why the author had chosen to quote or paraphrase. Students turned off their cameras and did this work on their own for five minutes. Since this was the first of several practice exercises lined up for that day, I did not yet ask students to share their findings, but simply to pause for reflection on their own.

<18>Next, we explored how to generate these rhetorical moves. Featuring a sample paragraph from a prior course reading, the next series of slides varied by color-coded text, and each prompted students’ input (see Figs. 8 and 9). For instance, after a student read the paragraph aloud, I asked everyone to identify phrases they felt represented the passage’s main idea. They did this work silently, and then I called on volunteers. We moved to the next slide, where the paragraph was replicated, now with phrases highlighted (based on my predictions of what they might identify, and which they indeed did). Afterwards, I turned to a slide that contained only the highlighted phrases—not the entire passage—and asked students to generate one-sentence paraphrases of these ideas (see Fig. 9). Each student typed their final sentence into Zoom’s chat box to share with everyone. We scrolled through these diverse offerings to point out how every sentence represented its writer’s unique voice and not the original.

<19>In the next segment of the lesson, we isolated quote-worthy phrases and, after a sequence of modeled sentences, practiced quoting and paraphrasing first from the sample paragraph and then from students’ researched op-eds. Students recorded their op-ed “they say” sentences into a shared Google Doc, and I commented in the margins while they were writing. (see Fig 10). I watched in real time as they revised and re-typed in response to my notes. In our next class period, we picked up with the slide deck and Google Doc in order to learn about, and then compose, responsive “I say” claims.

<20>In this way, slide decks provided a slew of benefits, and they continue to do so as I evolve my emergency remote teaching practices. In one crucial sense, slides help students to keep track of on-screen lessons, enabling them to re-focus whenever their attention wanders due to understandable “Zoom fatigue” (Jiang; Schroeder). I learned this when students shared, after being asked for feedback, that they “appreciated seeing the discussion topics on screen, so [we] have time to think about them before participating” and that slides “prevent that trap of missing a few seconds of a call and being unable to jump back in with full understanding.” In addition, slides can account for momentarily broken audio due to Wi-Fi instability. Keeping in mind the tenets of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), slideshows let me deliver information simultaneously in auditory and visual formats and vary that visual delivery in different graphic and orthographic orientations (“The UDL Guidelines”). Moreover, since I store the collected decks as PDFs on the course website, they give learners an opportunity to return later to any day’s material and think it through at their own pace. Finally, slides aid me with organizing lessons during this time-strapped year.

From Connectivity to Connecting: Screencasts in Fall 2020 and Beyond

<21>While these interactive slideshows suited my synchronous courses, I needed to figure out how to present comparable material to my asynchronous students, those learning within a Canvas-only platform. Given my time constraints, I recognized it would be possible, even simple, to adapt synchronous slideshows into screencast videos (recordings of the desktop screen accompanied by audio narration). Not only did screencasts allow me to produce dynamic audiovisual content to enhance the otherwise depersonalized delivery of text-heavy LMS pages, but they also led me to begin experimenting with other approaches to video recordings beyond the conventional parameters of a narrated slideshow.(2)

<22>In these ten-to-fifteen-minute videos, I explain key concepts to students who are encountering course material solely online. In various videos, I present, for instance, adapted iterations of the “they say / I say” slideshow discussed above. In others, I do not use slides but, instead, alternate between web pages and PDFs to demonstrate important topics such as internet research or close reading (see Fig. 11).

<23>For online as well as “live” courses, screencasts have been proving invaluable for distributing information that might otherwise be addressed during in-person class time, such as how to navigate our digital platforms. In addition to content-based lessons, I have produced simple five-minute screencasts to show students how to access an online course portal, work through weekly modules, or use peer review tools; how to launch and interact with Perusall; and where to locate my feedback on graded assignments in Canvas. I have created screencasts showing how to navigate a course’s Wix website and how to create blog posts for the site (see Fig. 12). Many times, at the end of a week, I realize I have not explained something in adequate detail; now, rather than send a lengthy email, I spend ten minutes setting up and recording a screencast. Then, I send students a link to the video, thus cutting out potential frustrations and frantic midnight emails from confused students. No matter their time zone or location, each learner can listen to and watch—and pause—my video at a time convenient for them rather than scramble to send me a desperate query for clarity or, even worse, fester in silent confusion.

<24>One final application of screencasts promises tremendous payoff: providing feedback on student work, particularly on drafts of papers. I experimented briefly with this technique during Fall 2020, recording five-to-eight-minute videos in which I highlighted three overarching recommendations for revision for each student. To make a screencast, I generated an audio message alongside a video capture of my cursor highlighting and pointing to relevant passages in the paper on-screen, sometimes even typing in written annotations while I spoke as a way of planting visual reminders for the students within the document. Instead of asking students to wade through discursive feedback in marginal annotations—a convention that has led all too often to drowning students in impenetrable teacher-ese—I condensed my feedback into a mode that students could digest, and with which I could convey a tone of encouragement rather than seeming to point only to weaknesses on the page. I tried my best to recreate in these screencasts the semblance of an office-hour encounter, conducted asynchronously.

<25>After sending out half a dozen of these trial screencasts last semester, I asked students during an optional video-conference session how they had felt about receiving this kind of feedback. Their response was overwhelmingly positive. Generously, these students expressed concern that I would be spending too much time producing such videos. Ironically, I told them, the screencasts were often saving me time.

<26>I did, however, discover some caveats while experimenting for the first time with this tool. Looking back, many screencasts are too long (four-to-five-minute segments would be preferable to lengthier fifteen-minute ones), and they are not punctuated by the solicitation of student input the way my “live” sessions are. Many videos capture vocal tics like “um” and “right” in too-fast speech or linger before changing pages, potentially losing students’ attention. Accessibility was also an issue, as no simple tool allowed me to produce captions during or after recording in a timely manner, which would have assisted all students with processing the audiovisual delivery.(3) Most of all, they were tiring. With forty students in two online sections, for instance, I could not muster the physical energy to create a large batch of videos consecutively in a single day. I have since learned to plan to space out production work over successive sittings.

<27>Aside from mechanical blunders, however, screencasts—even clumsily produced ones—can convey a degree of liveliness that connects with students across geographic and temporal distances. While they watch me navigate materials on-screen and listen to my voice rambling in their ears, online students can feel more attuned to my teaching presence, which, as many educators have observed during this emergency remote situation, is “particularly important for students enrolled solely in online programs” (Kelly). In many senses, that is all of us.

Future Directions

<28>The one unavoidable limitation with any screencast-driven communication, however, is that no matter how personalizing, they reinforce unidirectional delivery from teacher to students. Unintentionally, screencasts leverage hierarchical power structures that lack the integration or coordination of unique student voices. In future iterations, I plan to ask students to create their own screencasts throughout the semester, perhaps assigning learners to respond to my feedback with their own three-to-five-minute videos. They could outline how they plan to tackle a paper revision, for instance, or narrate their unique interpretive analysis of a literary passage after watching a video modeling my own close reading.

<29>Indeed, at the close of Fall 2020, I offered my online students an opportunity to create a multimodal reflection presenting one key takeaway from the semester. Many chose to generate a screencast or narrated slideshow. I was delighted to sit at my desk listening to each of their voices explain their growth over the term, and it made me wistful that I had not been able to get to know each of them better. Exchanging a set of screencasts back and forth over the duration of a semester—from their home to mine and back again—could be one way for students in an asynchronous course to feel authentically seen. While I have found a number of ways this year to speak effectively with my students remotely through our screens, such an audiovisual correspondence could allow me, in turn, to recognize every student’s fullest presence.

<30>After all, we strive to be a community of voices. Let’s hear each one.