<1>The year 2020 was difficult for much of the world; yet in Hong Kong, one might say that 2020 began in 2019. That summer saw mass protests, followed by conflicts between protesters and police when the Hong Kong Police Force began withdrawing legally-obtained permissions to gather.(1) By November 2019, universities in Hong Kong went online as campuses transformed into medieval-like fortresses, some of them even becoming battlegrounds between activists and police. The pandemic began in January 2020, followed by mass arrests and a canceled election. In the midst of so much change, university teachers faced difficult questions about how to teach students who might be traumatized by the weekly, sometimes even daily, transformations of their city. Then, on June 30, 2020, the Chinese legislature in Beijing passed the National Security Law (NSL) without input from the Hong Kong Legislative Council. The NSL prohibits secession, subversion, terrorism, and “collusion with foreign forces” that might “endanger national security.” As a result, it posed security issues for online and hybrid learning, particularly in more “sensitive” subjects.

<2>In this pedagogy short, I will outline the course I designed and taught in Fall 2020 called “The Police in Literature and Culture.” I will also address how I adapted the course in the context of new restrictions on academic freedom and freedom of speech under the NSL. I created this course in the wake of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States with two goals: (1) to equip students with the skills and knowledge to think critically about literary and cultural representations of the police in the context of the global history of policing, and (2) to denaturalize the modern police and analyze its contingent and controversial history. By the end of the course, students saw Hong Kong policing not as an isolated anomaly but in the context of larger global, historical patterns.

Course Conception

<3>The course provides an example for how academics might teach crime and detective literature in the midst of global protests against police brutality and offers a model for “widening” the teaching of crime literature.(2) Scholarship and university coursework on detective and crime fiction, especially in nineteenth-century studies, frequently focus on the European and American detective.(3) My course de-centers American and European police literature while also encouraging students todraw connections between the literature we read and recent events in Hong Kong and across the globe. Moreover, I framed part of the course in response to the popularity of crime fiction and true crime, both in an Anglophone context and in Hong Kong Cantonese television and film. Contemporary crime fiction often places the police or people affiliated with the police in the role of the hero.(4) Similarly, many popular true crime podcasts take pleasure in the imagined or actual punishment of the “criminal” rather than offering a more nuanced understanding of state violence, the police, and criminal justice. In Hong Kong, there is a long-standing history of police films and television, often supported by the Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF). TVB, a local Hong Kong television channel, has served at times as an unofficial public relations branch of the HKPF. In 2019, TVB partnered with the HKPF to produce PTU 2019—which even featured actual police officers—to celebrate the police force’s 175th anniversary and to promote the Police Tactical Unit (PTU).(5) In the context of the 2019 and 2020 protests, however, the HKPF fell in popularity among many Hong Kongers, particularly the younger generation.

<4>By the time I taught “The Police in Literature and Culture”in Fall 2020, I had to rethink my pedagogical approaches to the topic because of widespread anxiety about the potential repercussions of the NSL on academic freedom and free speech. Since the 1997 handover from the UK to the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong has been a semi-autonomous region (SAR) with its own legislature, chief executive, electoral system, and judiciary. The NSL, however, significantly undermines Hong Kong’s autonomy. Anyone arrested under the NSL could be removed to mainland China and tried under mainland law. The law’s language—in Chinese and English—is framed so vaguely that some offenses are open to broad interpretation.(6) It also gives police extensive new powers that include the ability to raid premises without a warrant and to order internet companies to remove content.(7) While I was teaching the course, the HKPF’s national security unit launched a new hotline for the public to report on people suspected of violating the NSL. I will explain in more detail how I structured the course to be sensitive to students’ anxieties about the law without actively self-censoring or enforcing censorship on them.

Course Structure

<5>I structured the course around three units: (1) The History of Policing, (2) Novels Critiquing Policing, Discipline, and Power, and (3) Policing in Contemporary Culture.(8) The first unit focused on the nineteenth-century history of policing as well as literary and cultural depictions of the police, ranging from short fiction to cartoons. I devoted one session to the London Metropolitan Police, which some argue is the first modern, institutionalized police force, although other scholars look to the American South and West, citing examples such as the Charleston City Guard and Watch, which monitored the movement of enslaved people.(9) The students read Charles Dickens’s Household Words article, “On Duty with Inspector Field” (1851), alongside a lecture about early challenges to institutional policing, particularly in industrial centers such as Manchester.(10) This unit revealed that that the early development of modern policing was contentious from the very beginning. Many Londoners in 1829 viewed the new police as an occupying army, and Blackwood’s Magazine even called Watthem general spies (Mukherjee 52). In working-class districts throughout England, the police were resented as parasites; in the periodical press, they were called “blue plagues,” “blue drones,” and “blue idlers.” They were particularly unpopular among the working classes for the limitations they imposed on freedom of assembly in the streets and for their regular supervision of pubs, beerhouses, and other places in which the working class gathered.(11)

<6>In the next session, we read academic scholarship on “slave patrols,” the police, and the Klu Klux Klan in the American South, alongside Ida B. Wells’s “Lynch Law in All Its Phases” (1892). Then we considered examples of imperial policing, including Cao Yin’s “Policing the British Empire on the Bund: The Origin of the Sikh Police Unit in Shanghai” (2017) and excerpts from Illustrations of the History and Practice of Thugs (1837).(12) Yin’s article explores the use of South Asian police in the British Concession in Shanghai as well as in other colonies, including Hong Kong. In a recorded lecture, I supplemented Yin’s account of racialized imperial policing with background on the early history of policing in Hong Kong.(13) In 1844, the police were established in Hong Kong as a paramilitary organization based on the so-called “colonial police model” developed in Ireland, markedly different from the London Metropolitan Police. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, many Hong Kong police officers were Europeans and South Asians; Chinese police were not allowed on late-night duty, nor could they be stationed in European communities or be equipped with firearms until the 1920s (Ho and Chu 2, 3, 13).The colonial government used criminal justice to manage the colony, particularly through registration, census, and curfews.(14) Indeed, Chinese residents were not allowed to walk on the streets after 10 p.m. HKT for much of the nineteenth century. While some of my students believed that Britain is and was a model of freedom and liberalism, the session on policing practices in the British Empire and its Chinese concessions problematized this belief.(15)

<7>During this unit, students attended a virtual tour of Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, PA, which introduced them to the complexities and racial inequities of the American justice system.(16) Students were able to connect what they learned on this tour to their reading of Wells. We then reflected on the redevelopment of Hong Kong’s Victoria Prison Complex (dating back to 1841) into Tai Kwun—an arts, entertainment, and shopping center. The discussion invited the class to think critically about heritage culture in Hong Kong, leading one student to share a personal story. This student recalled that, during a visit to the new arts center a few years ago, an older relative burst into tears; the visit brought back painful memories of this relative’s experiences as a Vietnamese refugee who spent time in the Victoria Prison Complex as an “illegal immigrant.” This student’s story challenged other students to think about the ethnic, racial, and class-based inequalities in Hong Kong in relationship to their own experiences living in the city. It also challenged their perception that the HKPF and criminal justice system used to be “Asia’s finest” before recent developments.

<8>The second unit focused on two novels, Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907) and Megha Majumdar’s debut novel A Burning (2020), to introduce students to self-reflective literary engagements with policing and surveillance. The next time I teach this course I will omit Conrad in order to focus more extensively on twentieth-century policing and decolonization, but the students responded thoughtfully to A Burning. In its focus on the Indian criminal justice system and Hindu nationalism, A Burning offers a critical examination of state power and social inequality. It features three characters: Jivan, a young Muslim woman wrongfully accused of terrorism because of an impulsive Facebook post critical of the government; P. T. Sir, a physical education teacher who gains political power through testifying against Jivan, his former student; and Lovely, a hijra who aspires to become an actress while facing everyday prejudice. The novel is divided into three parts. Jivan narrates her story in the first-person present tense; Lovely narrates her section in the present progressive tense; and P. T. Sir’s section is told in the third-person. I selected this novel because it deals with issues that resonate in Hong Kong but does not require students to speak explicitly about local issues in light of anxieties about the NSL.

<9>In the final unit, we turned to non-fiction activist writing of the late-twentieth- and early-twenty-first centuries, which provided historical context for the Black Lives Matter movement, and then lookedto contemporary debates about police reform and abolitionism. Students read recent work in police abolitionism, including excerpts from Alex S. Vitale’s The End of Policing (2017) and JP’s “Imagining the End of the Police: What is ‘the Rule of Law’ in a Rigged Society?” (2019), which offers a vision of police abolitionism in Hong Kong. The course concluded with a final session on contemporary police procedurals, placing them in tension with abolitionist writings and the history we had studied over the semester.

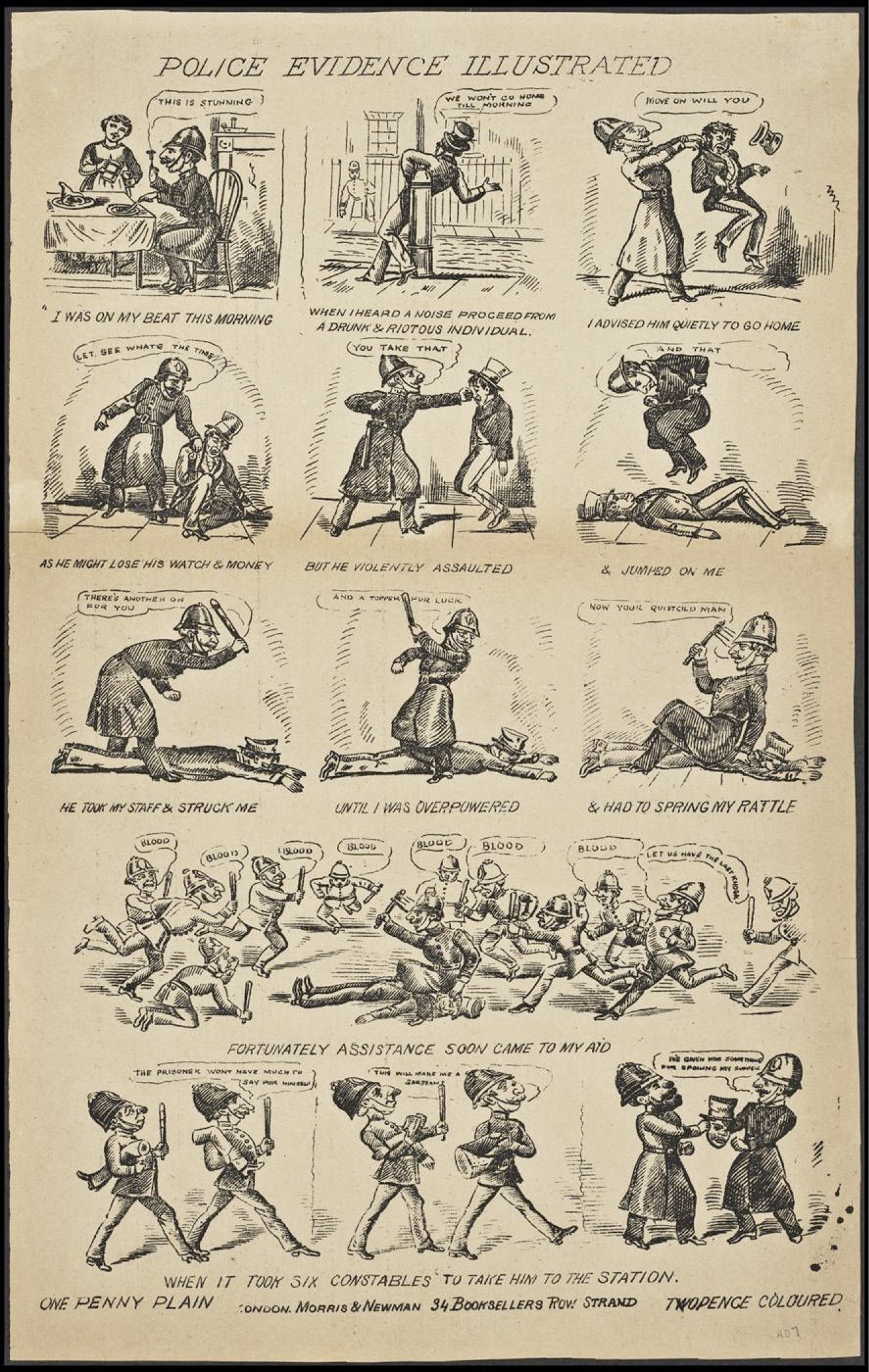

<10>The assignments were scaffolded so as to help students develop skills over the semester and learn to write analytically about a range of sources. In the first assignment, students selected a nineteenth-century artifact of popular culture and then analyzed its depiction of policing or discipline. This assignment (see Appendix 2) allowed them to explore online nineteenth-century archives and find unexpected continuities with ongoing contemporary culture and conversations. One student selected a nineteenth-century cartoon called “Police Evidence Illustrated” (see Fig. 1), which satirizes police violence by juxtaposing a policeman’s acts of violence alongside his whitewashed version of events. In the second assignment, students wrote an argument-driven academic essay about one of the two novels. For the final assignment (see Appendix 3), students had several options, including some creative ones. I decided to offer an unconventionally open assignment to invite students to explore the course’s relationship to their own recent experiences in Hong Kong without making it a requirement. Students could opt to write an academic essay, write a general opinion piece on an issue related to the course, or create their own creative project, accompanied bya brief analytical explication. Through this assignment, I hoped to instill in students the ways that non-academic modes of writing can also be critically reflective. One student wrote, performed, and produced a music video dramatizing recent events in Hong Kong. They based it formally on A Burning, writing the song from several different perspectives: the child of a Hong Kong police officer who idealizes her father, a teenage protester arrested by the same police officer, and a mother visiting her daughter, the teenage protester, in prison.(17) Another student wrote a poem, “Ging Caak,” that used Cantonese puns in English to explore recent divisions in Hong Kong society.This assignment allowed some students to integrate the intellectual content of the course with their lived experience.

Course (In)Security

<11>Since the NSL passed shortly after the course was approved and scheduled, I designed the course to respect students who might be anxious about inadvertently breaking the law. The first consideration I had was course delivery. I offered two sections of this class (“tutorials,” as my university calls them), with one section meeting face-to-face and the other section on Microsoft Teams, so as to address security concerns about Zoom. In university feedback collected in Spring 2020, students expressed anxiety about Zoom because, while it is a US-based company, its software is developed in China; this connection could make it vulnerable to pressure from the Chinese authorities. The university student union building even features signs of a Zoom icon with a big X over it (see Figs. 2 and 3).

<12>For both tutorials, I reserved the most sensitive topics for pre-recorded lectures to allow students to absorb the material in privacy. Each week, I recorded several short audio lectures, accompanied by PowerPoint slides and a written transcript. Students could listen, watch, read, or do all three, meeting needs associated both with privacy and with various learning styles. Another reason I chose this mode of delivery is that it is more easily accessible. Many students in Hong Kong do not have their own computer or a private space at home, so they use their smartphone and data plan to access course materials. Short recorded lectures also allow students to listen at their own pace depending on their particular learning needs. One student wrote that this approach “made the lectures [feel] more like podcasts. As a result, I wouldn’t feel quite as overwhelmed having to watch all lectures by myself, since online learning requires much more self-discipline than usual.”

<13>By offering as many options for participation as possible, including one-on-one consultations with me, I sought to be sensitive to students’ anxieties about the new law while also giving them the opportunity to contribute to ongoing discussions. During online tutorials, I gave students the option to participate by video, audio, text chat, or they could email me their thoughts if they preferred not to share their ideas in front of the class. When we discussed writings on police abolitionism, I warned students in advance and excused their absence if they felt uncomfortable attending. Students appreciated this option. One wrote in an evaluation, “Some subjects are really difficult to talk about, and she not only foresees but understands us empathetically. Right from the start, she said that we can sit out of classes, or contribute however much we’d like to in class if the topics are too uncomfortable for us.”

Global Conclusions

<14>I originally designed and proposed this course in early June 2020; once I had to teach it, however, Hong Kong had been transformed by the NSL. Instead of canceling the course, I diversified its mode of delivery to address students’ concerns about the NSL, surveillance, and hybrid learning and construct a learning community in which they could feel as safe as possible. The course gave students an intellectual environment to make sense of their contemporary experiences with protests and policing, including those experienced personally and viscerally both in Hong Kong and elsewhere in the world. Although based in the unique context of Hong Kong, this course provides an example of how classes in crime literature can move beyond national and regional boundaries. Rather than contributing to the local or national echo chamber that many students inhabit, a global approach allows students to view their world in more analytically and historically complex ways and to see patterns and connections to the world outside their borders.