<1>In the Fall of 2020, while writing in their informal journal about their struggles with online education during the pandemic, one of my students wrote an earnest question that has been sitting with me ever since: “Who invented school?” Written while enduring the immiserating combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and emergency remote learning, the question’s simplicity struck me—not just as an existential plea, but also as an unexamined conundrum because, after many years of teaching, I really did not know how to answer.

<2>Since the outbreak of the pandemic, we have lost nearly a quarter of our enrollment at Hostos Community College in the South Bronx. Already the second smallest of the twenty-five campuses that make up the City University of New York (CUNY), our pre-COVID-19 matriculation included around 7,000 students.(1) As an assistant professor of English, I help to shepherd first-year students through their two requisite semesters of writing composition. Reading students’ informal journals has been an important strategy I have used to understand their educational histories and learn about their academic and personal goals. I give students great leeway to choose what to write about, but one suggestion I make as a topic—since it is of interest to me professionally and also helps new students craft an identity as a college student for themselves—is to write about their educational path. What was their childhood education like? What sort of student did they consider themselves in high school? What are the best and worst educational experiences that they have had? Students tend to be uncomfortable at first with this assignment because they do not quite buy the call for “informality” nor my prying interest in their reflections. They often object to the quantity required (250 words, twice per week), but over time usually grow fond of the opportunity to write so freely.

<3>In these pandemic semesters, informal journals have been one of the few ways in which I can truly get to know individual students, and using Google Docs has helped me build these relationships remotely: access is free and available across platforms; I can easily comment on their entries; and students can respond to my comments with their own, in turn. Some of the warmest exchanges occur in the digital margins of our shared documents. Students illustrate their journals with memes or photographs of their family members—some of whom have been sick with COVID-19, others from whom they’ve been separated this year. Part of the success of this low-stakes assignment lies in the fact that I do not pose many restrictions about subject matter, nor do I grade them on anything beyond the word count. I simply ask students to write about what they are thinking about—and since they are relatively new to college, education tends to be a popular subject.

<4>This particular student’s question about “who invented school” stood out to me because, in its simple exasperation, it was also a question about gatekeeping and obstacles. I had gotten to know this student’s struggles through their journal: they are working full-time at a supermarket in the Bronx, paying college tuition, and aspiring to join our college’s nursing program. They left most of their family in Ghana a few years ago to pursue their education here. The pandemic has increased the difficulty of their already difficult path. When New York City (NYC) was the epicenter of the pandemic in the Spring of 2020, as I learned through their journal, seven of this student’s co-workers died from COVID-19, and many more were sick. In Fall 2020, there were a few weeks during which I lost touch with them; when they finally emailed me, I learned that one of their brothers had died from the virus back home in Ghana. In this context of struggle, their question about “who invented school” struck me because it was a moment of anger for them—they were struggling to keep up with their classwork—and it prompted me to reflect on my role as their instructor. Between the student and the future they imagine for themselves lie many classes like mine, many high-stakes assessments to determine their access to specialized programs, and many, many more months of tuition. It is easy to see how the obstacles might feel insurmountable, and it makes sense to wonder if this system we call “education” is really doing what it is designed to do.

<5>I begin with this student’s question because it reminded me of a phrase bell hooks quotes from Terry Eagleton’s The Significance of Theory (1990): “Children make the best theorists, since they have not yet been educated into accepting our routine social practices as ‘natural,’ and so insist on posing to those practices the most embarrassingly general and fundamental questions, regarding them with a wondering estrangement which we adults have long forgotten” (qtd. in hooks 59).(2) I do not mean to patronize this student by suggesting their question is “childish”; rather, I read it as the sort of inquiry that leads to the “best theorizing” we can be forced to do in higher education. The deeper I delve into their query, the more I am convinced that the United States education system does not do justice to its students. The pandemic has laid bare the gross inequities in the US education system, and, since its educators are likely to spend the next few years sifting through the damage of this horrific catastrophe, those of us who teach in it might as well take this opportunity to rebuild something better. From what I can gather, as I try to figure out who “invented” the education paths students follow in this country, the inequity that the pandemic has exposed for everyone to see is neither new nor unintended. In the late nineteenth century, popular eugenics theories and industrial standardization processes inspired the innovators who implemented US primary, secondary, and higher education systems. Policing students’ language has been an important strategy for promoting and demoting students along the way. Privileged white students’ consistent success in education in relation to their peers who are students of color is no coincidence in a system designed to maintain white supremacy. Perpetuating inequity—retaining existing power structures along race and class—was the goal all along.

Policing a Myth: Standard English

<6>One first step toward ending educational complicity in the white supremacist project of the US would be to stop policing a phantom known as “standard English” in students’ writing. Though many teachers have been professionally empowered to monitor it, “standard English” does not exist. This is a fact. In the US, there is no equivalent to the Academie Française,for instance, a French institution that has existed since 1635 and that sets explicit rules about lexical and grammatical matters. Though there is no US equivalent to this institution, but students in this country face what Vershawn Young calls “language bigotry” in the college classroom all the same as they are so often measured against a language standard for which teachers cannot, in good faith, produce evidence (117). As Young notes, it is an insult that compounds a battery of institutional injuries faced by students—particularly those of color—on their educational path (117). This path is so abusive that it would certainly prompt my thoughtful student to wonder “who invented” it.

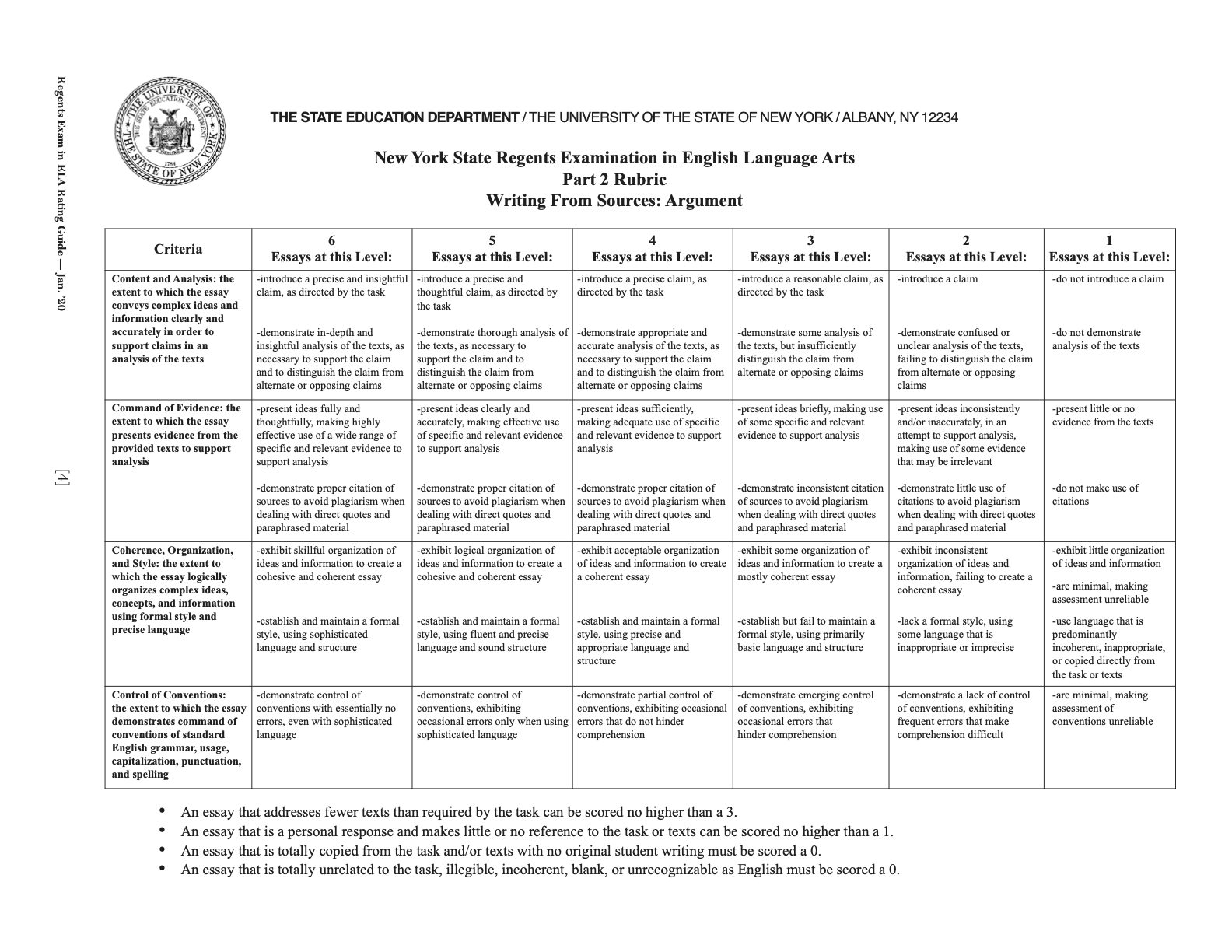

<7>Take the standards by which most of my students here in NYC have been assessed for their entire educations: from the Regents exams they take to get a high school diploma, to the assessments they take at CUNY to earn access to a credit-bearing course, to their college courses. A pattern emerges in all of the materials structuring these particular assessments: assessment rubrics refer to the mythical “standard English” without acknowledging what that phrase means. The Common Core Standards for English Language Arts, & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects is a standards system created by the Obama administration in 2010 and adopted to varying degrees by nearly all states.(3) The document uses the phrase “standard English” forty times. Students in New York State, which adapted all of its standardized exams to reflect the Common Core Standards, can earn a so-called “Regents Diploma” if they achieve a 65 or higher on their Regents exams in various subjects, including English Language Arts (ELA). The ELA Regents rubric repeats the language of the Common Core document, claiming to assess a student’s “command of conventions of standard English” (“Regents Examination; see Fig. 1). Students who graduate with a “Regents Diploma” in NYC are guaranteed a spot as an undergraduate at one of the state’s CUNY campuses, where standardized test-taking does not always end.

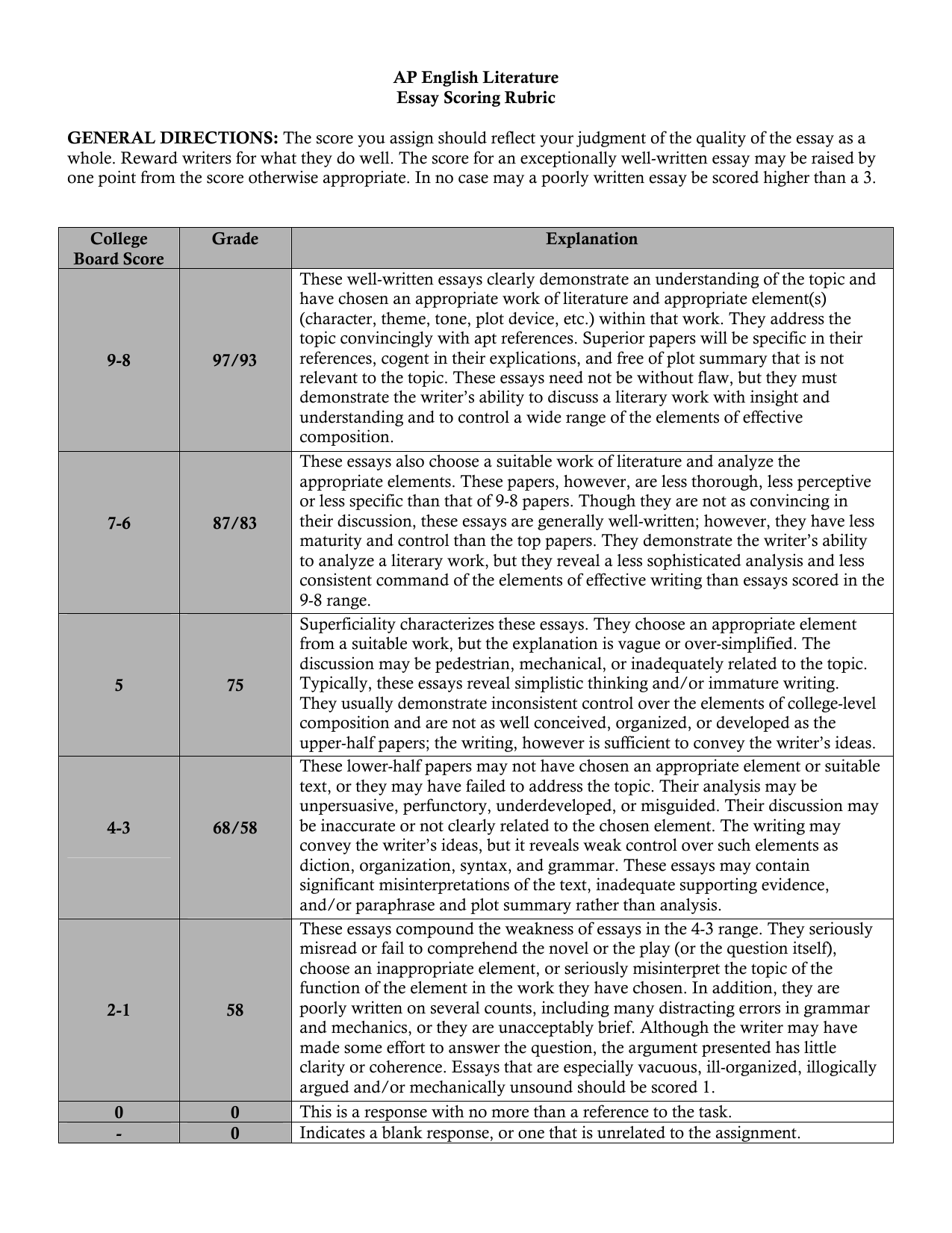

<8>Until this year, CUNY students had to take the CUNY Assessment Test in Writing (CAT-W) if they were deemed “not proficient” on the basis of low-passing Regents scores (see Fig. 2). Though it changed significantly in 2019, the Advanced Placement (AP) English literature rubric from the College Board used across high schools in the US still proves little different in its values from other NYS standardized tests (see Fig. 3). Following guidance from the older rubric, essays could be considered among the “lower-half” if they demonstrated “inconsistent control” and revealed “unsophisticated thinking and/or immature writing” (AP English Literature and Composition 4). Conflating “thinking” with “writing,” as the “and/or” suggests, is a habit characteristic of a long lineage of racist linguistic practices as detailed below. The College Board’s new scoring rubrics include a category called “sophistication,” which they define as a trait of an essay that “[d]emonstrates sophistication of thought and/or develops a complex literary argument” (AP English Literature Scoring 3). This revision suggests a relationship between sophisticated thinking and a student’s ability to make a “complex literary argument”—though the “and/or” here suggests that one could exist without the other. This particular revision removes reference to the mechanics of writing composition, allowing “sophistication” to do all the dirty work that “unsophisticated thinking and/or immature writing” had done before.

<9>What is the reference point to which all of these assessments refer, one might reasonably wonder? Educational documents cannot will “standard English” into existence simply by using the phrase repeatedly. Gavin Jones’s “‘Whose Line Is It Anyway?’: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Language of the Color Line” (1997) provides the insidious history of how literary representations of Southern dialects after the Civil War artificially distinguished between white and Black speech and reified distinctions that were not necessarily there to begin with. Jones notes how, at the time, it was in fact widely believed that Southern Black speech was the greatest influence on everyone’s speech—and white Southern speakers adapted Black English so thoroughly that white and Black speakers were often indistinguishable from one another (21). Jones notes that Du Bois described language as an early site of segregation, noting how separating Black from white English became “just as important” as “social segregation” in the aftermath of the Civil War (25). Literature often did the dirty work of elevating white over Black speech in order to impose hierarchy where none existed: in writing from the period, “black speech was exaggerated in its ‘lingual barbarisms’ while white speech was ‘revised according to Noah Webster and Lindley Murray’” (23).(4) Young’s analysis of Jones’s essay is equally important as it notes that “white speech was represented in print as correct, even though in practice it was just as incorrect as black dialect when compared with grammar books and dictionaries” (116). Grammar books and dictionaries had less to do with deciding who spoke properly than the literary authors who represented them.

<10>Today, no one wields grammar books and dictionaries against student writers quite like composition instructors do, and at the 2019 Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC), Asao B. Inoue reminded his colleagues of the high stakes of their language-cop practices in a talk entitled, “How Do We Language So People Stop Killing Each Other, or What Do We Do about White Language Supremacy?” He cautioned his audience that,

If you use a single standard to grade your students’ languaging, you engage in racism. You actively promote White language supremacy, which is the handmaiden to White bias in the world, the kind that kills Black men on the streets by the hands of the police through profiling and good ol’ fashion prejudice. (11)

As I write, it has been nearly a year since police officers murdered Breonna Taylor—not in the streets but in the sanctity of her own home. The trial of George Floyd’s murderer, also a police officer, just began this week in early April 2021. Education systems and police forces share much in common, and Inoue’s connection between the two carries all the more weight as people in the US witness the disproportionate impact the pandemic has had on people of color. Rather than addressing that which caused higher education to go online in the first place by reducing the spread of COVID-19 and developing pedagogical practices that do not rely on paranoia, institutions purchased aggressive surveillance software trained to invade students’ personal spaces and even their web browsers.(5) If it seems like educational systems are colluding with the police to reproduce the same racist inequity, a history of the former will make its resemblance to the latter seem less surprising. Since the time of Inoue’s talk, the goal of systemic change has animated the Black Lives Matter protests in the streets and even in the government, and the very least educators can do right now is examine how they assess their “students’ languaging.”

<11>White language supremacy haunts American classrooms and streets in equal parts. When teaching composition to first-year students—nearly all of whom are people of color and most of whom come from households earning below $20,000 per year—I spend a few days every semester covering “figurative” and “literal” language. Figurative language facilitates a great deal of violence, I always explain, which is why, as a class, we need to understand it when we hear it. For instance, in a trip to Kenosha, Wisconsin, following the police shooting of Jacob Blake, the former President of the United States used a golf metaphor of choking at an easy putt to explain why cops sometimes kill Black people (Bosman). This type of figurative language illustrates how language first dehumanizes people and then facilitates their deaths. Rhetorical tricks can deliberately distract audiences from what is at hand: dead bodies, and primarily dead Black bodies. These are bodies killed by the state—the same state that funds my job, the same state that ran out of personal protective equipment in March and April of 2020, and the same state that writes the rules that govern educational standards. Here in NYC, I am paid from the same coffers as the cops who choked Eric Garner, brutalized Abner Louima, shot Amadou Diallo, and killed one of my former students in 2011.

<12>Before the pandemic, the subway station near my campus had been populated with New York Police Department (NYPD) officers hoping to catch fare-evading riders. Students and staff alike passed through this phalanx, greeted by campus security immediately on the other side of our college’s doors. Many students attended high schools that had metal detectors and armed school safety officers from the NYPD. I take seriously the fact that I, too, represent yet another extension of the government that polices impoverished neighborhoods like the one in which I teach. hooks writes that such recognition is “crucial” for students to feel safe to speak in classrooms, given the fact that those who teach occupy a “society that remains white supremacist, that uses standard English as a weapon to silence and censor” (172). Given the visibility of police on and around my campus, I try to remain vigilant about the ways in which I can easily replicate and even benefit from the carceral system that makes up part of the fabric of my college’s community. My policies about student language and the ways I assess it fall well within the scope of that vigilance. As I am a white person in the middle of a highly policed community made up of people of color, I am explicit with students about the politics that govern how instructors police language in schools.

<13>Citing the 1974 statement of the CCCC entitled “Students’ Right to Their Own Language,” Young reminds readers that, as “scholars have long observed[,] . . . Americans tend to believe that whites speak and write better than blacks when they really don’t. Consequently, whites are often led to believe their speech is standard when really it’s not” (117). In Other People’s English (2013), Young, Rusty Barrett, Y’Shanda Young-Rivera, and Kim Brian Lovejoy cite Frederick Williams’s bracing 1976 study about how teachers’ prejudice about language is never really about language but about the race of those speaking it. Williams dubbed monodialectical white students’ voices over Black and Mexican-American students’ images, and they were nevertheless “rated as poorer speakers of Standard English” (Young et al. 36). The issue made tangible by this study is not merely the invalidity of standard English, but the fact that even when teachers agree on the standard (as these teachers had), their racism overrides their ability to assess students’ use of it anyway. Young et al. conclude rightly, in my opinion, that changing “language ideologies that have a negative impact on minority children needs to be a basic, fundamental, inherent component of language education” (36). Educators often perpetuate prejudicial ideologies that they have internalized, and there is less distance than some might want to admit between policing the language of people of color and policing their bodies as well.

<14>So why assess students based on a standard that does not actually exist? To create better writers? To hone critical thinking? I doubt it. And to what degree do these assessments merely measure a student’s relative insulation from the existential stress in a time of pandemic? No one ever said that studying for the Regents and then the CAT-W made them a better writer—certainly not during the higher stresses students are facing while meeting these benchmarks during the pandemic. There is something more insidious at play. Fred Moten answered some of these questions once, and the answers highlight the colonial origins of English language in the US in the first place. In public conversation with Robin Kelly on the subject of “Do Black Lives Really Matter?” Moten said, “Settlers always think they’re defending themselves. That’s why they build forts on other people’s land. And then they freak out over the fact that they are surrounded” (qtd. in “Fred Moten and Robin Kelly Ask”). What are academic institutions defending credit-bearing classes from when they use these standards to prevent students from even entering them? Using language standards rooted in racism means that institutions are making sure that certain voices are authorized and accredited while others—unauthorized voices—remain silent. In NYC, the Regents authorize educational credit on the basis of whether students transgress the unwritten regulations of a colonial language on stolen Lenni Lenape land. The irony is remarkable.

<15>Here is where some of the violence is born: these standards conflate “thinking” and “writing”—but writing is a technology, not evidence of an ability to think. And as the pandemic has laid bare for everyone, usually people’s ability to use a technology well is dependent upon their access to it. Implicitly allowing white language supremacy to stand in for what state-sponsored rubrics term “command,” “clarity,” and “maturity” is a way to disguise a white supremacist project with claims to rigor and objectivity. Meanwhile, over a century of scholarship—from Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) to William Labov in “The Logic of Non-Standard English” (1972) to Jones (1997) to Young et al. (2013) and Inoue (2019)—has made the case that judging a person’s intelligence based on their dialectical proximity to a vaguely defined form of English is not just racist, it fails at its own task. In perpetuating these standards, whiteness becomes, in Sara Ahmed’s terms, the “here” from which all else is oriented (151). So-called “standard English” is a “point from which the world unfolds, which is also a point of inheritance,” an orientation from which “whiteness ‘holds’ through habits” (154, 156). In perpetuating this malignant habit, many educators become enlisted into the cause of white supremacy, gatekeeping the socioeconomic mobility so often tied to a college degree and losing out on hearing voices and ideas that merit attention. By relying on rubrics and grading metrics, which bear all the hallmarks of officious nineteenth-century scientism, educators at all levels certify facility with white language as evidence of intelligence. It is long past time to bring this practice to an end, particularly given the emergency conditions—resulting from COVID-19, continued white supremacist violence, and a contentious election—under which students are trying to learn.

The Industrial Roots of Standardization

<16>The standardization of what was considered to be “good” English shares origins with the American educational system’s emphasis on standardized testing. Standardization has deep roots in nineteenth-century industrialization and the proliferation of bureaucracy that emerged to support it. Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit, published between 1855-57, offers us an example of how nineteenth-century bureaucratic methods often end up undermining the very systems whose well-being they are designed to support. In the novel, a well-intentioned character named Daniel Doyce has invented something that promises to “effect a great saving and a great improvement” in industry (Dickens 127). Doyce’s project gets so endlessly stuck in an approval process required by the various departments of the government’s “Office of Circumlocution” that he ends up selling his invention to Russia instead. The motto of this fictional office is “HOW NOT TO DO IT” (113, caps original). The novel deftly parodies the nineteenth-century bureaucracy which, instead of imposing order on the chaos of an industrializing society, exists only for the sake of sustaining itself and in so doing, effects more chaos. Little Dorrit’s most searing critique is reserved for the government whose burdensome oversight processes undermine its own national interests. Doyce’s champion, Mr. Meagles, laments the inventor’s thwarted patriotism, insisting that he “has been trying to turn his ingenuity to his country’s service”—but to no avail (119).

<17>The problem standardization aims to solve is a real one: How can massive institutions assess quality and efficiency except through bureaucratic means? And when the bureaucracies built to support them cannot authenticate institutional outcomes meaningfully, what do institutions do? The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing educational institutions to find out the answer to this question as I write. For instance, the College Board—the century-old testing service that administers the Scholastic Aptitude Tests (SATs) and the AP exams for college-bound high school students in the US(6)—is in turmoil because the main mechanism of its credibility—surveillance—is impossible with the deadly airborne virus forcing test-takers to stay home. Facing widespread condemnation for its early handling of test administration during the pandemic, according to a recent investigation by Forbes, the College Board is collapsing under the weight of 2020’s $200 million revenue losses (Adams). The investigation reports that “more than 1,600 four-year schools will not require SAT scores for admission in 2021”—and that list of schools includes the entire Ivy League (Adams). As Ezekiel J. Dixon-Roman, John J. McArdle, and Howard Everson have shown, Black students consistently score much lower on the SAT, the test administered by the College Board, than their white counterparts (14). The SAT is also notorious for its ability to predict students’ family incomes rather than their ability to succeed in college.(7) Since the SAT is a test whose origins in eugenicist science make its racist outcomes unsurprising, the only real surprise is that its credibility has endured this long. How did something as ineffective as Dickens’s Office of Circumlocution become the arbiter of college admissions in the first place?

<18>The US education system is filled with such seeming paradoxes, resolvable only by seeing them for what they are: implements designed to promote white supremacy under the guise of objectivity. One might well argue that the ill-suited pairing of pedagogy with dehumanizing industrial design was just another strategy of white supremacy, woven into the fabric of US institutions as the country’s economy reinvented itself following a major economic crisis and the Civil War. In addition to being the year that Dickens published the final serialized installment of Little Dorrit, 1857 also witnessed the US’s first major financial panic. In fact, Charles William Eliot—whom Cathy Davidson calls “the person most decisively responsible for designing the modern American research university”—blamed the panic on the country’s outdated higher educational system (18). Davidson explains that Eliot, a tutor and former student at Harvard, “believed that the outdated Puritan college . . . was inadequate to the task of preparing future managers and leaders of America’s new technology-driven industrial age,” and he spent the rest of his career reforming education as a result (18).

<19>Davidson’s The New Education (2017) opens with an important account of Eliot’s transformation of university curricula, noting that US contemporary institutions owe their current diverse course offerings, majors, minors, professional schools, and breadth requirements to Eliot’s work. The restructuring of universities occurred in deliberate coordination with the industrialists (Rockefeller, Carnegie, Cornell, Vanderbilt, and so forth) whose ill-gotten profits funded the universities in the era of these transformations (37). Eliot and his peers looked to industry for a model of how to scale up education in the US: “Standardization of labor practices of measurements, of productivity quotas became key to the management of factories and assembly lines—and came to influence a new approach to higher education that increasingly relied on quantitative metrics as the means for certifying quality and expertise” (37). By harnessing what Jack Schneider and Ethan Hutt call the “seeming precision” of numerical assessments and standardization in classrooms, educators could make a case that they, like their industrialist peers, were objective, scientific, and therefore effective (201).

<20>Misgivings about standardizing assessments used to distribute students into institutions and predict their success, anathema to humanistic philosophies about education and the ways in which students learn, are well-founded. As Davidson so trenchantly notes, “A century of studies has revealed what learning is . . . Yet we have not incorporated these findings about active learning into the institutional practices of most of our elite universities” (42). Instead, education systems continue to rely on nineteenth-century industrial practices better suited for the factory than the classroom to assess students. Numbers can appear objective, and nothing is more seductive to institutional design than the apparent cleanliness of quantitative metrics based on a standard.

<21>The relationship between the factory and the classroom was explicit during the time in which schools and universities were scaling up: the surge in industrial jobs that compelled people to immigrate en masse and compelled those already living in the US to move into crowded cities also created dense populations of children to educate. According to David B. Tyack, between 1890 to 1918, “[a]ttendance in high schools . . . increased from 202,963 to 1,645,171, an increase of 711 percent while the total population increased only 68 percent” (183). Joe Feldman’s Grading for Equity (2018) documents the imposition of factory-like assessments in schools that resulted from this boom in enrollment, noting that curricular priorities included “(1) punctuality, (2) regularity, (3) attention, and (4) silence,” according to “a document signed by seventy-seven college presidents and city and school superintendents of schools in 1874” (Feldman 21).(8) It tracks that these assessments would suit the profit-oriented purposes of the philanthropic robber barons underwriting the “new education” Eliot was developing in the US. Educating and employing the masses required some method of bureaucratic evaluation and assessment to help distribute labor efficiently. In response to this surge of new students in crowded cities, schools enacted policies designed to do exactly what Franz Fanon describes: “instill in the exploited a mood of submission and inhibition which considerably eases the task of the agents of law and order” (3-4). It is no coincidence that these changes were made at the very time that the Bureau of Indian Affairs sponsored boarding schools with the explicit intent to “kill the Indian . . . and save the man” (Pratt 46). Policymakers saw formal education as a means by which to prepare “the diverse, unruly mass of immigrants, rural transplants, and the poor” for the “discipline and habits that factories prized in its assembly-line laborers” (21).

<22>In the late-nineteenth century, the liberation of formerly enslaved Black Americans in the South and mass immigration of people to the US from Eastern and Southern European countries stirred racist and xenophobic anxieties among Anglophone whites in the US. The growing popularity of eugenics at the time provided philosophical relief for policy makers intent on implementing oppressive policies. Eugenics followed on the heels of Charles Darwin’s advances in evolutionary biology. A failed English academic named Francis J. Galton used both magicians’ tricks and scientific-sounding words to promote his theories about improving the human race through deliberate breeding (Black 52). He coined the word “eugenics” in his 1883 text, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Development, a book that sought to elevate human breeding to a numerically predictive science (53-54). In spite of his lack of actual data (an omission to which he himself confessed), Galton’s theories proliferated abroad, becoming the basis of everything from intelligence tests used to determine who could become US military officers in World War I to the foundation of Joseph Mengele’s research on human prisoners in Buchenwald and Auschwitz during World War II (56, 42).

<23>Galton’s dedication to the appearance of scientific objectivity—“Whenever you can, count” was a favorite expression of his—became a foundational principle of the educational assessment methods his field of pseudoscience directly inspired (52). Ajtha Reddy’s deft legal scholarship on “The Eugenic Origins of IQ Testing: Implications for Post-Atkins Litigation” (2008) explains that, “Eugenic validation of existing race and class hierarchies functioned tautologically: privileged ethnic groups were considered innately talented and biologically advanced” (667). This tautology explains why children of former (mostly white) Harvard students are, to this day, five times more likely to be admitted to Charles Eliot’s illustrious institution,(9) and why wealthy white parents have been willing to risk imprisonment to ensure that their children experience the elite education that is a hallmark of their status (Taylor). A recent article in The Atlantic by Caitlin Flanagan concludes, devastatingly, that “you don’t want to know” how few students from the average US public school actually end up being admitted into elite Ivy League colleges.

<24>So how did the US get from Galton’s falsified experimental outcomes and mentalist tricks to the twenty-first-century education system predicated on an unprecedented amount of testing and students’ personal access to inherited wealth?(10) Reddy details how Henry H. Goddard, the “father of intelligence testing” in the US, created his own version of French psychologist Alfred Binet’s intelligence test and administered it at Ellis Island in 1913. Goddard found the “intelligence of the average third-class immigrant” to be “low, perhaps of moron grade,” and noted that recent immigrants—those coming in from Southern and Eastern Europe, notably—were “of a decidedly different character from the early immigration. . . . We are getting the poorest of each race” (qtd. in Reddy 671). These were not fringe theories: Reddy notes that the pseudoscientific work of Goddard and his colleagues “dominated the academic discourse of their day and soon began to wield significant governmental power” (671).

<25>Eugenics testing became official in the US when, in response to a demand for military officers as the country mobilized for World War I, psychologist and Harvard professor Robert Yerkes deployed versions of Goddard’s tests to assess recruits. His tests, which “relied heavily upon knowledge of elite and urban pop culture, as well as test-taking proficiency,” apparently passed muster (672). Results “reinscribed Nordic supremacy: eighty-nine percent of all African Americans and forty-seven percent of whites, mostly from southern and eastern European countries, were deemed morons” (672). On the basis of Yerkes’s successful work with the Army, a Princeton psychologist named Carl Brigham developed the “Scholastic Aptitude Test,” first administered in 1926 (672). He believed Yerkes’s tests confirmed “Nordic supremacy and the racial inferiority of virtually everyone else,” and students have been taking his SAT ever since (Black 132).

<26>The standardized exams that we use to quantify student learning, born from Galton’s movement, continue to reproduce racial and class hierarchies. It is no surprise, then, that they originated in this toxic pseudoscience, one which self-consciously strove from its inception to wield numbers in order to appear convincing, even in the absence of data. Eugenicist methods, promoted as “scientific” and therefore objective, efficiently solved the problem facing education leaders in the years following World War I—that is to say, if the “problem” was the prospect of Black Americans and recent immigrants accessing educational institutions and profiting from industry. Using pseudoscience, leaders could claim to preserve the promise at the heart of US democratic ideals—that “all men are created equal”—while preserving the hierarchies that proved so profitable to the industrialists funding the most elite educational institutions. It was in the years that directly followed the deployment of these intelligence tests—assessments, let’s be clear, that have never actually measured intelligence—that contemporary US methods of assessing students became widely used.(11) Metrics developed by eugenicists are still reproducing the effects—racism and inequality—that their racist designers intended.

<27>Students are not widgets, and strategies to meet their learning needs cannot be mass-produced; intelligence cannot be measured by a eugenicist’s tests. Allowing the seductive power of industrial efficiency to guide education policy since Eliot’s “new education” model was implemented in the US has resulted in nothing short of educational apartheid (Kozol 9). Given the racist origins of the standardized assessments used to divide students, this discriminatory educational system has been the goal all along.

Pandemic Transgression

<28>When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in the early months of 2020, students and instructors alike were facing grave illness and fear, all while learning how to learn and teach online. Since the conditions under which instructors had planned to assess students that semester had been drastically altered, it only seemed fair that the way instructors graded students would change as well. An Inside Higher Ed article written in April of that first pandemic semester by Colleen Flaherty asked, “How lenient, or not, should professors be with students right now?” Historian Kevin Gannon responded to her question using a trenchant metaphor, observing that “grading as if things are ‘normal’ . . . ‘strikes me as the equivalent of giving someone a swimming test during a flood’” (Flaherty). Fortunately, many colleges allowed students to elect a pass/fail option for their transcripts in acknowledgment of everyone’s extenuating circumstances (Burke). And in this particular moment of upheaval, educators might finally be in a position to break free from eugenicist-inspired assessment practices, ones which were designed a century ago to promote racism and maintain an elite class who would profit from labor.

<29>An easily transmissible airborne virus changes even banal daily-life activities with the prospect of a violent death. But when Louisville police murdered Breonna Taylor on March 13, 2020, in her home and when Minneapolis police publicly lynched George Floyd in broad daylight on May 25 that same year, these acts of violence called public attention to the fact that daily life was already violently charged for many people in the US. These unlawful executions at the hands of the state ignited what the New York Times dubbed the “largest movement in U.S. history”: by early June, “half a million people turned out in nearly 550 places” to protest (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel).(12) By the end of Spring 2020, the trauma of racist violence combined with the fact that Black and Latinx people in the US were dying of COVID-19 at greater rates than white people in that same country put nearly all pre-pandemic professional concerns into dire perspective (Kendi).

<30>When surrounded so completely, as everyone was in Spring and Summer 2020, by scenes of trauma and the prospect of death, many educators were forced to face their assessment practices and consider the role they played in contributing to students’ suffering.(13) This essay takes seriously the charge leveled by hooks in Teaching to Transgress (1994), that the “vast majority of our professors” reproduce the trauma of their own educations, using “the classroom to enact rituals of control that were about domination and the unjust exercise of power” (5). The history of standardized assessment in the US bears out the truth of her assertion—that American education perpetuates these eugenics-inspired assessments, and many of those who teach in it have internalized the idea these metrics mean their teaching is more objective. Most college instructors have little or no training as teachers,(14) nor have most spent any time learning the history of the educational practices they reproduce in the classroom (Stommel). The consequence of this ignorance is that, to this day, higher education is woefully inadequate and continues to reinscribe principles promoted by the likes of Galton, Goddard, and Yerkes. The assessments that colleges use to select students in the first place continue to perpetuate the same stratification of race and immigration status explicitly celebrated by these eugenicists. By using these metrics to authenticate intelligence and so-called scholastic aptitude, colleges validate the same racist organizing principles that ensure disproportionate state violence against people of color.

<31>Even the best-intentioned among educators can often behave like the “well-intentioned bank clerks who do not realize that they are serving only to dehumanize,” as Paolo Freire put it in 1968 in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (75).(15) Without an adequate chance to examine pedagogical methodology or to truly learn about the history that led to the status quo in the US, even with good intentions, educators can perpetuate a system that bucks against the way students learn.

Transgressing for a Change

<32>Upon learning the history of educational practices in the US, educators who oppose racism should be prepared to change. To do so requires upending over a century’s worth of educational practices, ones that are written into the very institutions that have delegated academic credentials in the first place. But if education is to be something better than abuse and oppression, then educators must do what hooks proposes: transgress. The exigencies of the pandemic and the visceral suffering of the Black Lives Matter movement have made it imperative to do so now, in spite of what institutions might mandate. Like Dickens’s inventor Daniel Doyce, transgressing—refusing to uphold supposedly objective “standards” of assessment—might make you a “public offender,” a “notorious rascal” in the eyes of the state, but at least you will not be participating in a system designed by eugenicists to maintain white supremacy (118-19).

<33>In his critical autobiography, Young clarifies that it is not just the fact that educational institutions impose an ill-defined standard upon students of color, it is also the “methods that teachers use to get students of color to use it” (113). These methods are harmful, and they do not work anyway. Many colleagues attribute their enforcement of “standard [white] English” in the college classroom to what Young calls the “seductive” promise of upward mobility—what I often call the “job interview straw man” (“What about when they have to go to a job interview?”) (113). Young challenges the premise of this argument, proposing that educators do better: “Our job should be educating students, not refashioning them into what we imagine the ‘marketplace’ demands they should be” (112).

<34>A first step for educators would be to resist falsely objective “standards” that, like the colonial forts built on stolen land, are without merit. In her essay on “Language” in Teaching to Transgress, hooks explains how she deliberately creates space in her classes for students to “use their first language” so that they “do not feel that seeking higher education will necessarily estrange them” (172). Informal journal assignments, like the one I describe in the beginning of this article, are one strategy teachers can use to deplatform standardization and teach students that their voices have value—even in classes besides composition. As I explained, one of the biggest challenges I face when I give my journal assignment is that students are unsure of how to write informally for a professor. It usually takes a few rounds of “grading,” in which I give students full credit for simply reaching the minimum word count, before they believe me when I say that I am interested in both the substance of their thoughts and the style in which they express them. Another way I communicate this interest in students’ voices is by enlisting them in the assessment of their own writing portfolio at the end of the semester. This method prioritizes revision and one-on-one meetings over the individual high-stakes essay grades and tests that once made up the bulk of my assessment practices. Finally, remote teaching has prompted me to adopt a “no excuses necessary” policy when it comes to deadlines and requests for assistance.(16) Students have shared many stories of trauma and hardship with me during the last year, but these stories have only convinced me further of how important it is to allow them to take care of their personal lives without having to perform a sort of “confession” to me. I communicate this to students explicitly—that they merely should stay in touch when they need to take time for themselves, they do not owe me any sort of personal explanation for their late assignments.

<35>In the book that inspired this collection’s name, hooks reminds her readers that “the classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy,” but a student’s access to that radical space is not guaranteed, and their status in the academy is monitored by a system of assessment that is racist and therefore violent (12). In researching and evaluating the history of assessment practices in the US, I grow convinced that it is incumbent upon educators of good conscience to quit adhering to the standards set forth by institutions to measure student achievement. Educators need the courage to transgress against these norms because, as the historical record shows, these norms were designed just over a century ago by eugenicists to meet the needs of an industrializing economy.

<36>“Who invented school?” has burdened me since I read my student’s journal. While chasing after the answer, I have learned that I perpetuate the pain that compelled the student to ask this question in the first place. I still do not know “who invented school,” but I do know why my student would feel compelled to ask this question. Over email recently, a student apologized for submitting late work, explaining to me that multiple recent COVID-19 deaths in their family had kept them preoccupied for a couple of weeks. That they apologized told me everything I needed to know about how they viewed the authority I held over them as a professor, in spite of my efforts to communicate my open policies about assignments. Long-held habits run deep for educators and students alike, even in the midst of what should be a time of solidarity and support: rather than a source of inspiration and joy, college is a place of dehumanization and surveillance.

<37>Du Bois offers a vision of education in The Souls of Black Folk that remains elusive over a century after he wrote it: “the true college will ever have one goal,—not to earn meat, but to know the end and aim of that life which meat nourishes” (59). Far too many people are forced to worry about “earning meat” at the expense of nourishment. This once-in-a-century pandemic has put institutional norms into submission, and while the College Board is still licking its wounds and as the Biden administration prepares to redeploy standardized tests,(17) educators have the opportunity to imagine anew what students deserve. One need only look at the distribution of the rich and the poor, the white and the non-white, throughout elite educational institutions and community colleges like the one where I teach to see that the nineteenth-century eugenicists who designed the American educational system have succeeded. One need only look at the state violence enacted upon Black bodies and the disproportionate number of non-white people incarcerated in the US prison system to understand that the habit of white supremacy is deeply ingrained. One need only look at how unfair the year of remote education has been for poorer students to understand how urgent it is for educators to change the US higher-education system. Doing so could be a useful first step in unraveling the systemic educational violence of the last century.