<1>I am an Adjunct Assistant Professor in English at Lehman College, a senior four-year college of the City University of New York. Located in the Bronx, Lehman College has a culturally rich and linguistically diverse body of students. Over fifty percent identify as Hispanic; over thirty percent identify as Black; and more than fifty percent are first-generation college students.(1) In Fall 2020, when I was assigned to teach a long nineteenth-century literature course that would be conducted remotely in the midst of a global pandemic, I knew I had the opportunity to do something different. The resulting course, “Women Write the Empire,” seeks to decolonize the traditional British literary survey course by using Caribbean women writers as its anchors, a third of whom would likely identify today as BIWOC. Due to the course’s distance learning mode, I developed a multimodal writing assignment that utilizes the social media platform Instagram in order for students to practice writing for public audiences and to use their writing as a tool for social advocacy while showcasing archival material from the online collections of these Caribbean women writers.

Syllabus and Assignment Creation in the Age of Instagram and BLM

<2>Due to the ongoing pandemic, all English courses at Lehman College were taught remotely in Fall 2020. Therefore, I structured the class around a hybrid synchronous/asynchronous method using Zoom and the Discussion Board platform on Blackboard where students responded to weekly “low-stakes” writing prompts and replied to one another’s posts in a blog-like format.(2) However, this distance learning came with its own set of challenges: many Lehman students were juggling child and/or elder care, struggling with unresolved health issues, and navigating the rigorous demands of essential worker schedules. I understood that going remote meant that I could not replicate a face-to-face classroom experience. However, I could use this unprecedented moment to craft a syllabus organized around the principles of care and vulnerability, recognizing that teaching remotely ushered in the potential for student-centered learning using digital pedagogies.(3) I re-envisioned traditional methods of student paper writing and applied a multimodal pedagogy that harnesses the social media platform Instagram for a “high-stakes” assignment (Elbow 11). An informal Doodle poll showed that all of my students were familiar—if not very familiar—with Instagram: they used it daily to post photos and vlogs, stay in contact with friends and family, meet new people, promote their brands, and follow popular public figures. By incorporating a digital tool with which students were well-acquainted, the predicted outcome was that they would be comfortable sharing their writing in this public space while still being challenged to think and write critically.

<3>Engaging with composition and rhetoric scholarship that promotes writing as a continuous practice and as a form of learning rather than its culmination, students completed a scaffolded digital humanities project that places an emphasis on archival research, audience awareness, revision, and oral presentation.(4) My intention with this assignment addressed the question: How can Instagram be used to enrich student learning, writing, and research?(5) Because their work would be public, students were required to keep their audience in mind and ask themselves the following types of questions: What helps me understand the literature and cultural artifacts that we are studying in this class? How do I present these materials in a manner that a broader audience would find accessible and compelling? My goal was for students to become proficient in the skills of close reading, critical writing, and archival analysis by using digital and public platforms as a way to work through—and write through—complex ideas and connect with real audiences. In addition, my pedagogical methods aligned with the notion that “the archive is no longer a professional space solely for specialized scholarly research at protected sites; undergraduate students regularly engage with digital archives,” and, in the case of this project, they would also take part in creating one (VanHaitsma 34). As such, the hope was that students would finish the end of the semester with the confidence and motivation to use their writing, archival methods, and digital technology skills in academic and non-academic areas of their lives.

<4>Having taught in the English department at Lehman College for ten years and having formed close mentoring relationships with many of my students, I can affirm that they are critical thinkers who actively engage in political and intellectual discussions and participate in community activism. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the Summer of 2020 highlighted Lehman community’s shared passion for social change as those of us who belong to that community remember and advocate for those who are made to live under duress as a consequence of anti-Black racism and its institutionalized impacts. As such, the decision to decolonize the long nineteenth-century survey course and craft a syllabus organized around women writers of the Caribbean and the Caribbean diaspora would, in itself, constitute a vehicle for progressive institutional social change. What better way, I thought, to challenge canonical structures than to pair these authors with multimodal pedagogies that also subvert traditional frameworks, such as the conventional term paper?(6)

<5>I was transparent with students about my intentions and, in order to bring our current-day politics into the classroom, I invited students to respond in writing to scholar Gurminder K. Bhambra’s opinion piece in the New York Times, “A Statue Was Toppled. Can We Finally Talk About the British Empire?” A lively discussion ensued about the glorification of the British Empire and how its history of colonization and enslavement shapes our present moment. One student wrote, “It’s amazing to see how Millennials and Generation Z (my generation) want to break the cycle [of] generations before . . . The taking down of imperialists and colonizers is important because it’s to write the kind of history we want for our future generations.” Another offered, “Instead of memorializing history by creating statues, I feel in-person discussions, lectures, or books should help to carry out the message of the social institution that was slavery. And not just half-truths, but [a] full acknowledgment of that which has left an imprint on POC.” This discussion not only gave students the opportunity to voice their arguments on the memorialization of history, but it also highlighted the pressing importance of this course’s undertaking: reading literature by BIWOC writers—many of whom have no statues dedicated to their lives and have been excluded from the nineteenth-century literary canon. For the purposes of this pedagogy short, I will outline the assignment guidelines and present student work from the course’s first unit and its companion project: Instagramming Caribbean Women Writers.

#blackgirlmagic: Instagramming Caribbean Women Writers

<6>During the first five weeks of the semester, students read and wrote about literature by the Caribbean/British authors Mary Prince, Mary Seacole, and Una Marson. The first “high-stakes” project asked students to visit the digital collections of these authors, choose one historical document, and write a 400-500-word narrative that connects the document to the primary text that we read for class.(7) After a multi-tiered drafting process, students posted their final piece of writing to the class’s Instagram page: @caribbeanwomenwriters.(8) The objectives for this assignment were for students to (1) practice writing persuasive prose for real audiences, (2) engage with online digital archives, and (3) create intertextual connections between the archival document and literary text. I made sure to advise students that this was not a traditional “close reading” essay that would be for my eyes only, and, therefore, I expected pointed, persuasive, polished, and evidence-based writing that critically presented unknown archival material from unknown authors. Students quickly understood that our use of Instagram was not merely for fun or convenience, but that we were using it as a tool for social change. By showcasing these Caribbean women writers, we had the opportunity to educate and inform the digital public.

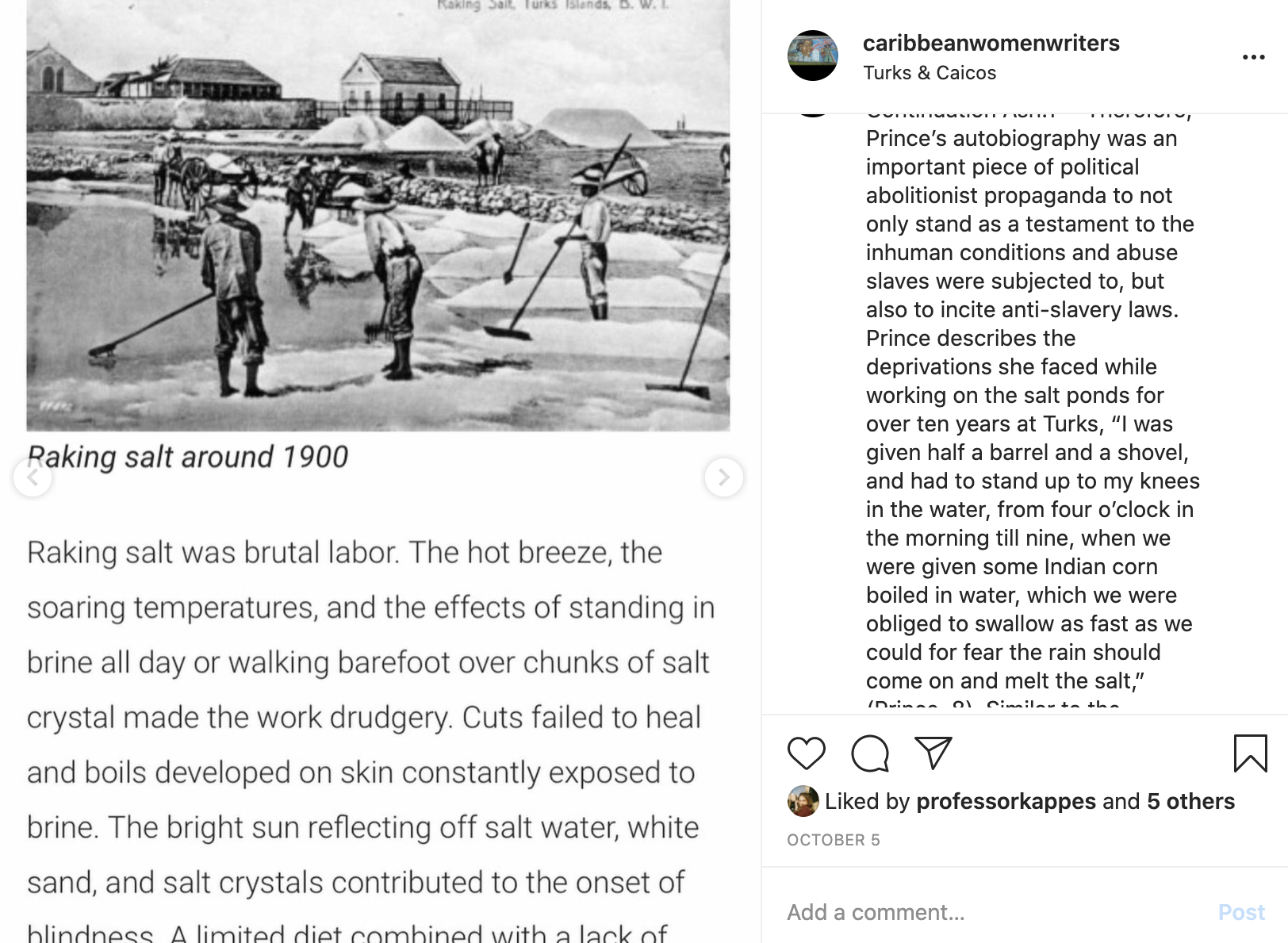

<7>Students had the choice of three digital collections, each related to the authors they had read. One of the works was the transcribed autobiography of Mary Prince’s The History of Mary Prince (1831), a raw representation of Prince’s experiences as an enslaved and eventual free woman in Bermuda, Turks and Caicos, Antigua, and England. I emphasized that one of the reasons for reading this narrative is because The History of Mary Prince, like many socially-motivated texts with graphic representations of slavery, have often been repressed and erased from literary canons, educational curricula, and current conversations about race. The result was that, in students’ online Blackboard discussions and on Instagram, Prince’s testimony and acts of social protest became instigators of meaningful conversations about the suppression of colonial and racial violence both in the nineteenth century and the present day. Having students first respond in writing to the text in the semi-private space of our class’s Blackboard LMS allowed them to work through their critical ideas in writing and personally navigate this emotionally-charged text. One student offered, “I will first preface this body of writing by stating the waves of emotions I experienced while reading this narrative . . . [even though] I am not ignorant to the vile and atrocious mistreatments that black people have been subjected to.”(9) In the next step of the project, students scanned the digital archival collections I offered on Prince, selected a historical document, and then composed essays for publication on Instagram. The resulting essays placed Prince’s text within its historical context while raising pertinent questions regarding her legacy. For example, a student posted about the Turks and Caicos National Museum’s digital collection on salt raking, connected it to Prince’s first-hand experience of this brutal labor in the salt ponds, and considered Prince’s narrative’s impact on today’s racial injustice (see Fig. 1):

Unjust acts today are continuously directed towards people of color, and Prince knew the importance of equality for individuals. It speaks volumes to read the horrific events she experienced and yet still there is some sort of disconnect, of what equality should be and how it can be properly executed. Flipping through what she endured and her success, we are left thinking about today’s world. Thinking of what impact does inequality have on certain races and genders within the 21st century, is there a reoccurrence from Prince’s 19th century world? What comparisons in Prince’s story do you see active in today’s world? #maryprince #caribbeangirlmagic #blackgirlmagic #strugglesinparadise #womenofcolorwriters

<8>What is critical about this student’s response is how they use Prince’s text and the platform of Instagram as a way to work through complex ideas about the dynamic of resistance’s historical impact on present-day activist movements. The student addresses both the troubling “disconnect” and weighty, moral responsibility that modern society feels when confronting the past traumas of women of color. The Instagram essay also reveals the student’s rhetorical voice, exhibiting a public persona that engages with current politics in order to connect with Instagram’s general audience through current points of reference. Moreover, the hashtags enact another form of rhetorical engagement. Here, they reposition Prince within the twenty-first century Black Girl Magic movement, invoked by public figures such as CaShawn Thompson, Michelle Obama, and Misty Copeland. As a result, the essay becomes a living artifact in all of Instagram’s #blackgirlmagic tags.(10) Also noteworthy is the student’s use of the hashtag #strugglesinparadise because it demonstrates another tone or persona that the student uses to sarcastically point to the challenges and traumas Prince faced while living as an enslaved person in the Caribbean. In the assignment guidelines, I encouraged students to experiment with hashtags, knowing that the platform of Instagram encourages “code switching” between these public personas. The use of these multiple voices can be read as a Bakhtinian heteroglossia as they represent social conflict and the tension between the central and marginal voices (Bakhtin 276). Though an unimaginable rhetorical technique in a traditional close reading essay, in this context, the students’ writing voices deliver an argument that inhabits multiple registers and can therefore pose various points of view that would otherwise have been repressed. In addition, these quips engage, incite, and persuade readers to “like” or “comment” on the post.

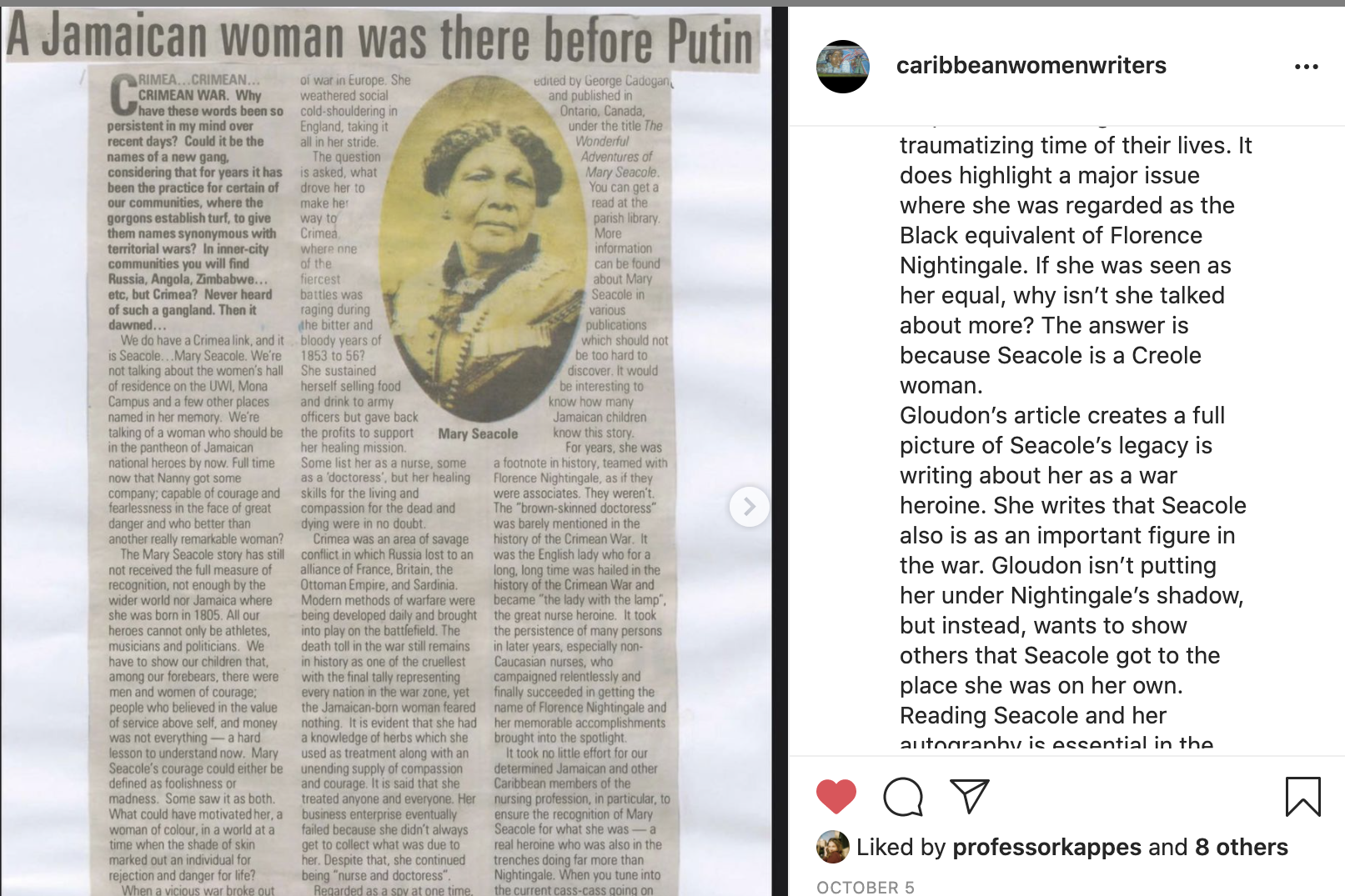

<9>Some students wrote about Mary Seacole’s The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (1857), which details the cosmopolitan life of the Jamaican British “doctress” and entrepreneur as she traveled through Central America, Russia, and Europe. This travel narrative/autobiography was chosen for this “Women Write the Empire” course because it proposes a challenge to Victorian England’s “angel in the house” archetype by showcasing the nineteenth-century global diaspora from the perspective of an independent Jamaican-born woman of mixed heritage. Students welcomed Seacole’s inclusion in the syllabus, as one student shared in a draft writing prompt on Blackboard’s discussion board: “From a personal standpoint, being a Jamaican woman myself, I took pride and honor reading Seacole’s story, because she was a woman from my yaad—my land of origin—who found her purpose and set out to be bigger than her little island. She reminds me of the women in my life [whom] I look up to and aspire to make proud.”(11) Having students wrestle with their profound personal encounters with these writers in draft writing allowed them to produce final essays that were rhetorically persuasive and critically astute.

<10>Other students followed the directive to scan the digital collections of the National Library of Jamaica and select a historical document, such as Seacole’s Last Will and Testament (1881) or a number of articles related to Seacole’s life and legacy.(12) One student chose a recent newspaper article from The Daily Observer, “A Jamaican woman was there before Putin,” in order to analyze Seacole’s unfolding legacy in the twenty-first century as compared to the obstacles that Seacole faced when attempting to create her own path of acceptance in the nineteenth century. The student critically considers that “[the article] does highlight a major issue where she was regarded as the Black equivalent of Florence Nightingale. If she was seen as her equal, why isn’t she talked about more? The answer is because Seacole is a Creole woman. Gloudan’s article . . . isn’t putting her under Nightingale’s shadow . . . It also highlights the importance of Black and mixed [race] women who are often overshadowed by their white counterparts in mainstream history’s narrative of events” (see Fig. 2). Using the hashtags #maryseacole, #blackwomenmatter, and #blackgirlmagic, this student’s Instagram essay attracted the attention of the Mary Seacole Trust, an organization established to “promote Mary Seacole as a source of inspiration for a fair, diverse and inclusive society, never again to be hidden from history.”(13) The Trust wrote comments on multiple students’ posts, expressing, “Thank you so much for sharing and raising awareness <3.” Instagram enabled student writing to extend beyond the confines of the classroom. Students were able to see the tangible and real connections that were possible through this form of advocacy writing, creating and entering into a network of digital knowledge production.

<11>Likewise, students resonated with the Jamaican British poet Una Marson’s anti-colonialist and feminist verse. On the Blackboard discussion board, I asked students to not only critically analyze a poem, but to also craft an argument as to which poem they found most emotionally affective.(14) A large majority of students wrote about Marson’s ballad “Kinky Hair Blues”: “As a dark skin[ned] black girl, my skin has always made me stand out. I remember always being the darkest girl in the classroom and hating my skin color when I was younger. I also didn’t like my hair because it was big and kinky . . . Those are my favorite lines because as an adult I grew to love myself fully and I wouldn’t change a thing about myself.” The themes of Black nationalism and female empowerment were showcased in the students’ Instagram projects, where some selected documents about Marson from the National Library of Jamaica’s digital collection. One student chose a review of Marson’s poetry and wrote, “Not only would her work fit well into the BLM movement, but for once, light should be focused on black writers who have called for effective social change and have sought to encourage women of color” (see Fig. 3). This student’s response is one of many that delineates their Instagram essays as tools to build new ways of collectively archiving and circulating material for those interested and committed to anti-racist thought and action in the twenty-first century.

Reflections and Thinking Ahead

<12>The course syllabi, assignment guidelines, and student work showcase how multimodal compositions on Instagram can provide new avenues of discussion regarding the future of student-centered writing practices, digital pedagogies, and nineteenth-century BIWOC writers as the anchors of course syllabi. In particular, the course’s student work exemplifies how pertinent it was to use nineteenth-century literature by BIWOC authors as a way to engage and work through current conversations about race. Instagram fostered a sense of togetherness where activism, awareness, and critical thinking created a virtual community as a placeholder for our former real-life one. In the age of Gen Z, the Millennial, and the BLM movement, we have been bombarded with the dynamic of resistance and anthem for immediate social change. What better time than now to experiment with digital pedagogies that foster student engagement, agency, and social justice?