<1>Preparing for my online Women Artists course in the midst of a global pandemic prompted me to redesign my undergraduate assessment measures. Instead of short-answer exams and research essays that asked students to analyze works of art and apply key concepts, I shifted toward active-learning assignments that drew inspiration from the Reacting to the Past (RTTP) learning model.(1) RTTP is generally a complex game that immerses students in the character of a historical figure to enact a nuanced, collaborative classroom exchange rooted in a significant event, like the French Revolution. Following bell hooks’s 1994 call to implement “engaged pedagogy,” April Lidinsky argues that RTTP has long been a part of feminist pedagogy and is well-suited to feminist subject matter because it promotes community building and empathy (hooks 15; Lidinsky 208). In addition, role-playing can elicit robust student engagement in a new subject, make course material accessible to at-risk students, and encourage student retention (Lidinsky 208). As I would find out, such an approach invigorated the virtual classroom.

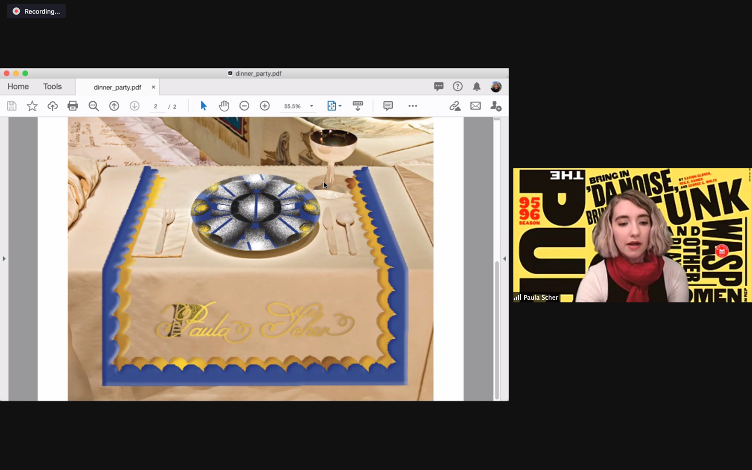

<2>My end-of-semester project invited students to attend a Virtual Dinner Party (see Fig. 1) based on Judy Chicago’s (1939–) iconic feminist installation The Dinner Party (1974–1979) (Chicago). The Dinner Party is an ideal work of art to support active learning. Its construction began in 1972 and necessitated the skilled labor of four hundred staff and volunteers. Participants collaborated in workshops to build the installation and took part in Consciousness Raising Groups, seminar-style discussions aimed at recognizing patriarchal thinking and shaping a feminist experience (Gerhard 600-9). Chicago’s working methods taught participants how traditional ideals of femininity imprisoned women’s minds and stifled their opportunities to pursue professional goals. Her “conscience raising” approach showed women how to be assertive, value their individual perspective, and execute high-quality work in a demanding environment. Their collaboration culminated in a monumental installation in the form of a banquet table that elevates the many women history has ignored.

<3>The Dinner Party first opened in 1979 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and is now permanently installed in the Brooklyn Museum. Outside the installation, there are six woven Entry Banners that include a poem conveying a unified worldview: “From this day forth Like to like in All things.” Visitors then enter a low-lit room where a large-scale triangle table set with elaborate place settings for thirty-nine guests sits majestically on a floor of gleaming white triangle tiles. Upon entrance, one is free to move around the table and study the installation. It feels as if one is the first to arrive at a party, but visitors may quickly realize that they can learn about the accomplishments of those who have been written out of history through the didactic aspects of Chicago’s work. Each side of the triangular table has a historical trajectory rooted in conventional grand narratives but with a feminist perspective: Prehistory to Classical Rome, Christianity to the Reformation, and American Revolution to the Women’s Revolution. From the ancient Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar to the Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c. 1654) to the American reproductive rights activist Margaret Sanger (1879–1966), place settings include handcrafted ceramic chalices and utensils as well as large plates with butterfly- and vulva-like forms and embroidered table runners specific to each figure. Chicago and her workshops handcrafted these materials as well as the porcelain-tile Heritage Floor on which the banquet table rests. For the Heritage Floor, they hand painted the names of an additional 999 women who literally and figuratively support the guests at the party. Outside the installation, Chicago also included Heritage Panels, reminiscent of poster presentations you might see at a conference, which provide further context about the accomplishments of the women included in the installation. Overall, The Dinner Party subverts the typical role of women at a party. Instead of serving as hosts, they become celebrated guests. In addition, it challenges the hierarchy of the medium. Typically, decorative arts completed in communal settings, such as weaving, embroidery, or porcelain painting, are associated with women’s work and are thus seen as less significant than oil on canvas or marble, for instance. The details in The Dinner Party, such as embroidered text contemporary to a figure’s time period, highlight the dedicated and skilled labor systems necessary to execute the impactful installation.

<4>The Virtual Dinner Party for my course took inspiration from Chicago’s artistic process and installation. I prioritized collaboration, helped to foster student agency, and called attention to the design, form, and limitations of the online learning format. To prepare for the project, my lectures introduced students to feminist art history and to artists from the Renaissance period through our contemporary moment. For example, we addressed issues surrounding patronage, racial identity, biopolitics, and western feminism. Toward the midpoint of the semester, students were instructed to select an artist, writer, or activist and to assume a role during an engaging class performance. Students could select a figure they encountered in lecture or in an assigned reading. I also encouraged them to research a figure they found on their own and whose work resonated with their particular interests. When our Virtual Dinner Party convened, students had to explain what factors contributed to history’s neglect of the figure’s accomplishments. In doing so, they were able to meet three goals: (1) to explore gender biases that are often hard to grasp through conventional learning methods, (2) reflect on the challenges of online learning, and (3) empathize with the historical factors that suppress the contributions of women.

Historical Background & Core Sources

<5>The impetus for the Virtual Dinner Party came from my study of the nineteenth-century work spaces of female artists. Although French Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot (1841–95) grew up in a wealthy family and enjoyed access to a studio with her sister Edma when they were young, art historian Anne Higonnet notes that Morisot did not have a studio of her own (a converted attic nonetheless) until she was forty-nine, after more than three decades of a dedicated and increasingly celebrated painting practice (202-3). The women artists of Victorian England fared no better. Deborah Cherry argues that the dimensions of architectural spaces in which female art students studied were comparatively smaller than those used by their male counterparts (58-60). Classrooms for women were often cramped and run-down, and separate spaces served to underscore gender differences. One of the goals of my assignment was to allow the restrictive format of Zoom (e.g., its small rectilinear space) to help students experience the confined spaces in which women artists created and learned. I thus drew attention to the ways in which muted microphones, cropped visual references, or a reliance on the chat feature interfered with our interactions. Reflecting on our Zoom experience prompted students to think about how they might use Zoom creatively to comment on the omission of women artists in art history.

<6>My course began with two foundational works of feminist art history: Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists” (1971) and Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock’s “Critical Stereotypes: The Essential Feminine or How Essential is Femininity” (1981). Discussing these two texts pushed students to consider the difficulty of dismantling gendered assumptions. Some students assumed that there were few important women artists prior to the twentieth century. Once they learned that there were many women artists, some who managed financially viable studios—like Artemisia and the Bolognese Mannerist painter Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614)—and others who co-founded significant movements alongside their male peers—like Morisot—the students had to confront the reasons for these artists’ effacement by art history. Classroom discussions and lectures prompted students to think about what led to the exclusion of female artists, while the online format of our Virtual Dinner Party acquainted students with the feelings of restraint and alienation.

<7>It is difficult for students to resist the urge to blame the past and assume a position of moral superiority. To counter this inclination, the course invited them to analyze the challenges art historians face when interrogating history. For example, we considered artistic agency and how our understanding of it shapes the value judgements we make about art. When interpreting Artemisia’s Judith Slaying Holofernes (1612–13), students considered whether they should heed Parker and Pollock’s call to refrain from interpreting her work within the context of her rape (20–25). How, we asked, does reducing Judith Slaying Holofernes to Artemisia’s assault obfuscate her innovative pictorial contribution? When the course discussion turned to The Dinner Party, students were primed to spot the difficulties of rewriting history and the significance of Chicago’s intervention.

Performance Setup

<8>Chicago’s The Dinner Party offers students a new way to explore history. For the Virtual Dinner Party performance, each student had to appear in their Zoom rectangle wearing a costume, with a changed name, and before a customized virtual background. Each student also had to present an Entry Banner, a tile from the Heritage Floor with one name, and a complete place setting.

<9>Preparation for the assignment began in the eighth week of the term with a detailed consideration of Chicago’s installation. When teaching The Dinner Party in a single week, I often focus on the table settings, including the embroidered tablecloths, the vulva-shaped plates, and the details that speak to each figure, such as the delicate pale-pink lace of American poet Emily Dickinson’s (1830–86) setting. However, since The Dinner Party served as a structural and conceptual underpinning of the course, I spent time laying out the project over the course of several weeks. In addition to the week’s reading assignments and discussion-board posts, students learned about each part of The Dinner Party and constructed their projects step-by-step: selecting their Dinner Party guest, brainstorming ideas for their presentation, choosing their Heritage Floor name, and deciding on their Entry Banner phrase.

<10>When we discussed Chicago, I assigned historian Jane Gerhard’s comprehensive article “Judy Chicago and the Practice of 1970s Feminism” (2011), gave a pre-recorded lecture that included a virtual tour of the installation, and provided links to the Brooklyn Museum site, which offers not only a glimpse of the table but a thorough overview of its parts.(2) Students responded to Gerhard’s overview in a discussion-board post by considering how Chicago subverted her patriarchal education when she, for instance, founded a Women’s Art Program in 1970. At the same time, students chose their figures and started to think about how they could use Zoom to pictorially convey fundamental concepts about those figures. I encouraged students to upload sketches and to list the ways they could use Zoom’s filters or identification factors to highlight or even obfuscate their figures.

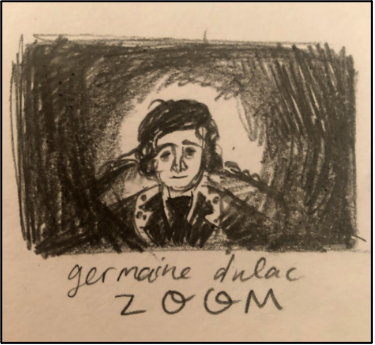

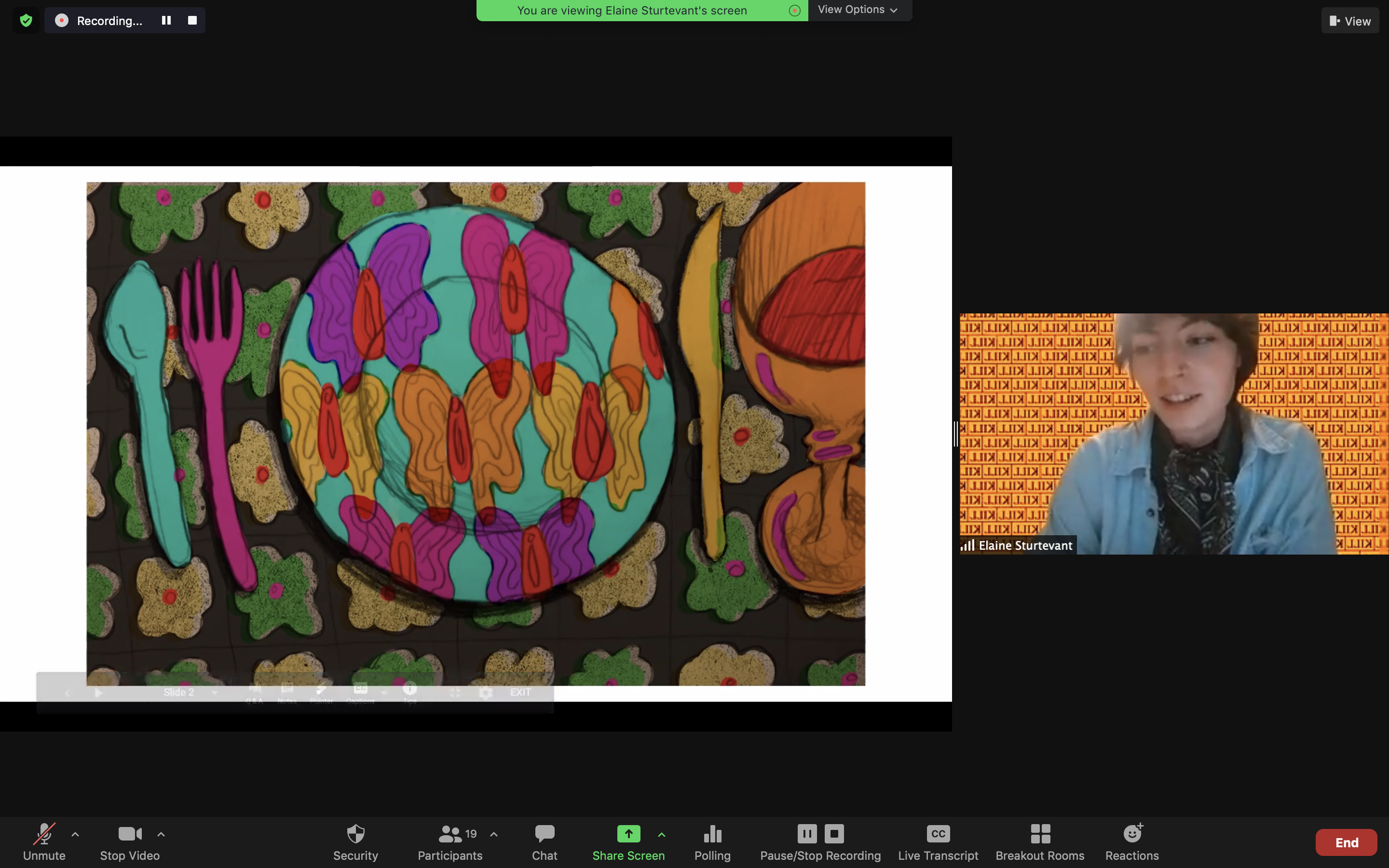

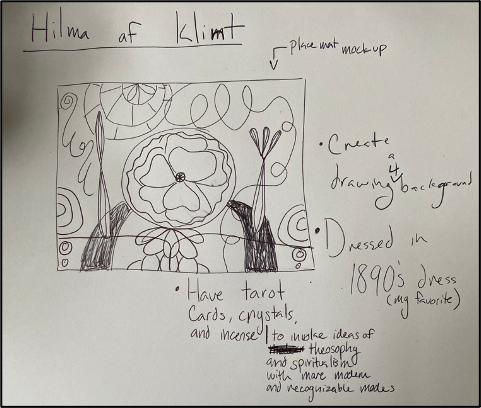

<11>In their sketches, students brainstormed how they could make connections between the marginalization of women and their use of Zoom to create a virtual presentation. One student, Sarah Boline, chose pioneering French filmmaker Germaine Dulac (1882–1942). Her first sketch for Dulac (see Fig. 2) took into account her computer’s inability to use a virtual background. Nevertheless, Sarah indicated that she would light her Zoom rectangle to “loo[k] like a circle . . . to emulate the visual elements Dulac uses in her films.” Another student, Brianna Bender, selected American artist Elaine Sturtevant (1924–2014). Brianna’s first diagram (see Fig. 3) included a wallpaper design that looked much like her final presentation (see Fig. 4). As she explained, Sturtevant, a little-known and controversial conceptual artist, “appropriated Pop-art paintings to challenge the concept of originality,” but she was often misunderstood by critics. To that end, Brianna sketched a repetitive wallpaper design reminiscent of American Pop artist Andy Warhol to appropriate from the Pop artist like Sturtevant. A third student, Mary Callahan, selected Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) and focused on the artist’s landmark 2018 exhibition at the Guggenheim. Making a connection to Nochlin, Parker, and Pollock, Mary pointed out that af Klint was overlooked by canonical art history narratives despite being one of the first abstract painters. Mary’s early place setting sketch includes a diagram that draws from af Klint’s mesmeric patterns as well as notes about props—tarot cards, crystals, and incense—to indicate af Klint’s ideas on Theosophy (see Fig. 5). Mary’s final place setting also echoed her initial idea (see Fig. 6).

<12>The following week, students selected the person to represent on their Heritage Floor tile. In a discussion-board assignment, I asked students:

Is there a predecessor for the woman you selected to sit at the table? Someone whose work or activism paved the way? For the Heritage Floor, you may think of women who were pioneers. They can be living, but they needed to have established some foundation on which our Dinner Party guests rest.

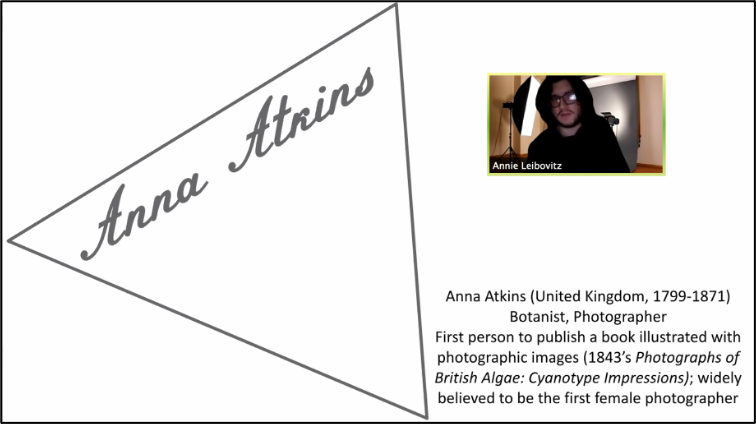

One student, Jack Leach, chose famed American photographer Annie Leibovitz (1949–) as his Dinner Party guest and selected British-born Anna Atkins (1799–1871), who is considered the first person to publish a book with cyanotypes, for his Heritage Floor. Students also chose fictional characters and political activists to reflect Chicago’s inclusion of the Snake Goddess from the Palace of Knossos, American abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), and American suffragist Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906). Olivia Schaffer, another student, chose the fictional genderqueer character Hedwig Robinson from Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001) and American activist Marsha P. Johnson (1945–92). A third student, Taylor Fennell, invited the American-based activist artists the Guerilla Girls and used German expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) for the Heritage Floor because “[t]he Guerrilla Girls hide their real identities by calling themselves names of great women artists from the past like . . . Kollwitz.” A brief screen recording I created explained how students could mimic the triangle of the Heritage Floor using a triangular shape in a PowerPoint slide.

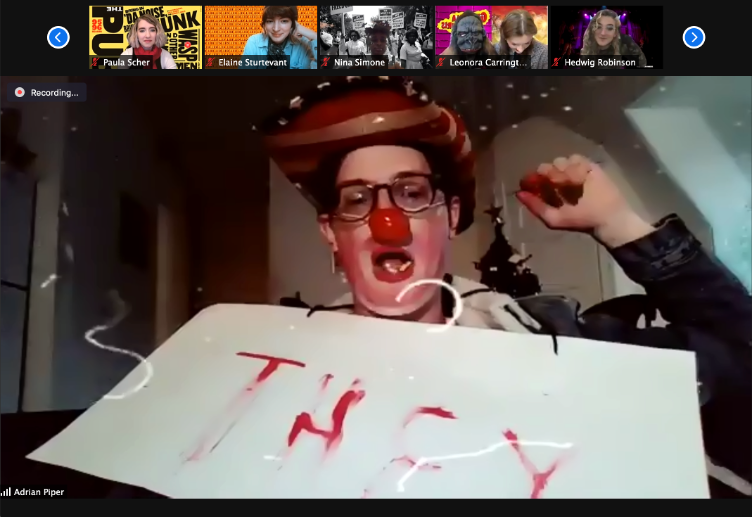

<13>Another preparatory week for the Virtual Dinner Party focused on the Entry Banners, which drew some of the most surprising and culturally relevant responses from students. In Chicago’s installation, six woven banners express a series of phrases that depict a world without division, an “Eden Once again.” Instead of seeing a utopian vision of unity, students were more forceful in their choices. One student, Haley Romansky, used “Nevertheless, she persisted,” a remark made by United States Senator Mitch McConnell in 2017 after silencing United States Senator Elizabeth Warren. Haley noted the quote’s importance to her and wrote that “it is proof that against all odds women will continue to rise back up.” Some students addressed racial differences. John Giltner, for example, chose conceptual American-born artist Adrian Piper as their guest (1948–) and made an Entry Banner that quoted her work: “It is in my own interest to confound crude stereotypes and bring the viewer to a greater awareness and acceptance of anomaly, singularity and individual complexity.” The student banners enabled them to express a point of view and highlight how words can carry powerful meanings. Similar to the preparation for the Heritage Floor, I used a brief screen recording to explain how a Zoom profile picture with a short text can appear when a computer’s camera is turned off.

Performance Structure

<14>Finally, I created a collaborative script to structure the Dinner Party performance (see Appendix 1). Since the course had nineteen students, I devised nineteen “parts” that allowed the students to manage the event. In the weeks leading up to the performance, students selected one part and wrote 100-150 words of dialog on a shareable document. The script included several emcees who made sure everyone presented in a timely fashion; another role required a student to offer an overview of the 1970s Feminist Movement; four additional parts asked students to provide introductions to the works of Nochlin, Parker, and Pollock; other parts asked them to introduce the different aspects of Chicago and her installation. The goal of the script was to ensure that students participated throughout the event. Rather than have students present their Entry Banner, Heritage Floor, and Dinner Party guest all at once, I arranged for students to each present their Entry Banners one at a time before moving onto the Heritage Floor. Students would thus participate at least four times. For each part of the performance—Entry Banners, Heritage Floor names, and Dinner Party guests—one student introduced the component, another student emceed by calling on the student to present, and a third student concluded that portion of the performance by connecting presentations.

<15>To conclude the script, I assigned parts that asked students to make connections to our historical moment. For example, Jesse Veasey noted that the year had been especially difficult and tested student motivation, yet he said that the Virtual Dinner Party enabled us to “immerse ourselves in the history of women’s art” and learn a lot in the remote environment. Likewise, Mya Williams poignantly noted that:

This year in particular is reflective of more than just an individual who is in power, but rather everyday individuals coming together for a synchronized purpose. The people in our Virtual Dinner Party have paved the way, introduced perspective, and broken barriers throughout history. 2020 has been a climatic year with a global pandemic, empowered groups, and systemic issues; thus, the collaborative aspects of our Dinner Party are especially relevant and important.

Some of the parts varied from delivering a short report to simply saying the names of a figure to be introduced. However, the script kept everyone invested in the performance. Although I intended for the script to merely play a practical role, it became a reflection of student struggles during this pandemic year as well as a celebration of learning as they commemorated women artists who themselves faced steep obstacles.

Performance

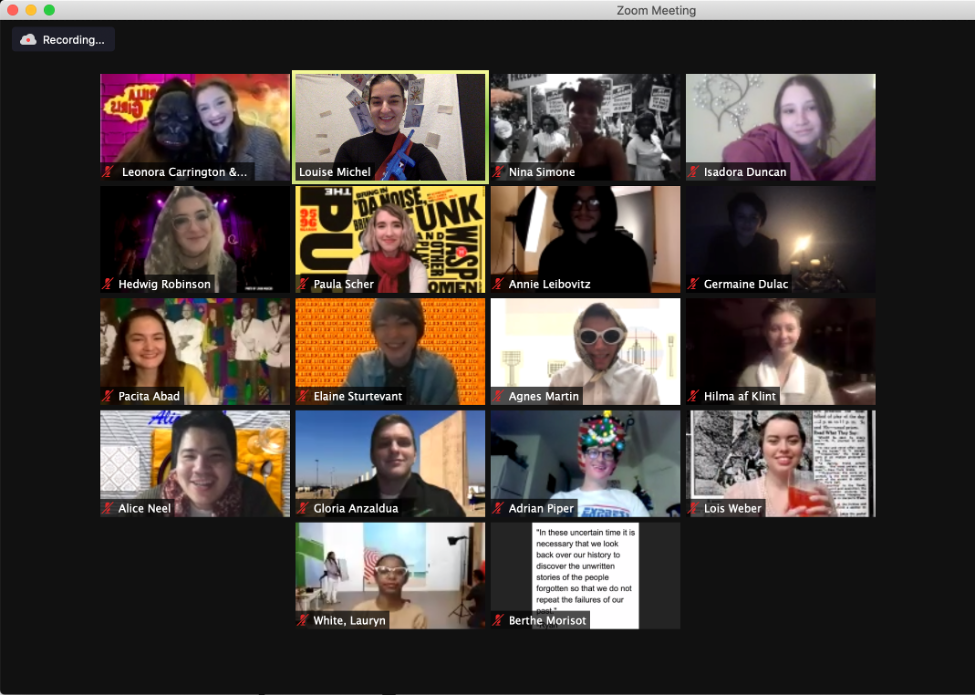

<16>The Virtual Dinner Party performance unfolded smoothly and took about one hour. As the class session commenced, I made all students co-hosts in Zoom and we turned our attention to the script to execute the event. Emcees called out names, and students presented their Entry Banners (see Fig. 7), Heritage Floor tiles (see Fig. 8), and introduced their Dinner Party guests and place settings (see Fig. 9) while also reading their prepared comments that explained their guests’ accomplishments and obstacles.

<17>The most effective presentations carefully considered the entire virtual space in a manner conceptually similar to Chicago’s installation, such as the embroidered table runners of the place settings. One student, Hayley Romansky, arrived dressed as American graphic designer Paula Scher (1949–) wearing a telltale scarf and used Scher’s customized font and color scheme as a virtual backdrop and for the place setting (see Fig. 10). John Giltner drew from Adrian Piper’s performances Catalysis (1970) and Mythic Being (1973) and adapted a filter that replicated the 1970s film of Piper’s performances (see Fig. 11). Luisa Maria Lynch selected Philippine painter Pacita Abad (1946–2004) and incorporated a woven place mat and wooden bowl in her virtual backdrop that related to Abad’s Philippian identity (see Fig. 12).

<18>In some cases, students did not have access to Zoom’s features but rose to the challenge nonetheless. Sarah Boline arrived as filmmaker Germaine Dulac (see Fig. 13) and used candles to give her Zoom rectangle a soft lighting that conveyed the quality of a black-and-white film. Students also drew directly from the vulva-like forms that appear on Chicago’s plates. Olivia Schaffer depicted transgender Hedwig Robinson’s plate with stiches across it to represent a gender reassignment surgery (see Fig. 14). Splotches of red indicate that the surgery was botched, and an overall color scheme of pink, white, and blue represents the transgender flag. From British-born surrealist painter Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) to American dancer Isadora Duncan (1877–1927), American portraitist Alice Neel (1900–84), and American singer and civil rights activist Nina Simone (1933–2003), students selected a diverse array of figures that revealed their interest in analyzing women artists and their role in history through a feminist lens.

![Fig. 14. Olivia Schaffer, Hedwig Robinson Virtual Presentation with Dinner Party Plate. This image depicts a Zoom window. On the left is a pink circle with the words “KNOW THAT YOU’RE WHO [full word not visible]” in blue lettering, beneath which are a series of white matchsticks with red tips.](images/14p_DIMARCO_FIGURE16.png)

Conclusion

<19>The challenge of teaching women artists in an online course was to develop an assignment that allowed the students to investigate and empathize with the roadblocks women have faced historically while at the same time analyzing their art. The Virtual Dinner Party accomplished both goals. Using an unusual presentation platform created an element of competition that pushed students to reflect on the relation between the virtual field, the artist, and her work. The reflection essays that they submitted after the performance cemented the connections between the various parts of their presentation and linked their ideas back to the work of Nochlin, Parker, and Pollock.

<20>In the future, I would like to adapt the assignment for an in-person class. To replicate the confining space of the Zoom rectangle, I could imagine asking students to use makeshift materials or found objects that mimic the limiting parameters that the students encountered in Zoom. Although I teach at an art school, the project would work well with non-art students and also suit literature or interdisciplinary humanities courses because Chicago’s The Dinner Party effectively asks viewers to recalibrate how they approach art and history. Her installation raises valuable questions that help instructors implement creative, thought-provoking assignments to transgress the evaluative measures with which we have grown comfortable. The Dinner Party ultimately teaches us and our students to explore competition, collaboration, and systemic, gendered inequities.