<1>My students don’t know how to use Zoom! This revelation floored me and came too late in Fall 2020 to revise my courses to account for it. Our school returned to face-to-face instruction in August amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout the semester, faculty received remote attendance accommodation requests for students moving in and out of quarantine on a weekly, if not daily, basis. This constant back-and-forth made in-person classes like mine necessarily HyFlex.(1)

<2>I’m a tenure-track Assistant Professor at an open-enrollment, rural college in the High Plains region of western Nebraska designated “frontier and remote” (FAR).(2) According to Fall 2020 enrollment statistics, my students are majority majority white-identified (79% to be exact); 88% are from areas of Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota; 41% are first-generation; and 60% are are female-identified. My school also has a significant non-traditional student population and a large number of students identified as “transitional”: students, often first-generation, who need additional support to succeed in their first year as undergraduates.(3) Some of my students come from high schools that had graduating classes with fewer than twenty students. Further, the majority of my students work at least part-time, and many have family responsibilities that, at minimum, divide their focus a few weekends each semester.(4) The pandemic exacerbated responsibilities for most of these students and increased their anxiety as their jobs became precarious, family members became sick (or passed away), or/and they themselves became sick. Plus, the emergency teaching situation ironically led to more online assignments and increased demands on their time.

<3>What I discovered toward the end of Fall 2020 is that most of my students knew what Zoom is, how to log in, and how to post to the chat. But those who did still had no idea how to apply that basic knowledge to engage effectively in class discussion or participate in active remote learning. In other words, they had never been taught how to learn with Zoom—or any other virtual meeting technology for that matter. As a result, my students genuinely didn’t understand how to contribute to a remote synchronous virtual learning community.()

<4>And why should they? The training they’ve received throughout their lives has focused on how to interact and learn in a physical classroom, not a virtual one.(5) Additionally, my students’ level of comfort with technology varied drastically based on their personal backgrounds and access to internet, computers, and new technology generally.(6) My working theory by the end of Fall 2020 was not that students hated or couldn’t learn from emergency remote instruction,(7) but that they had been set up to fail. In other words, they had not been taught how to learn under these conditions. Just as educators were asked to transition to teaching students remotely with no (or limited) formal training in remote instruction, students have been asked to learn remotely without any preparation. In Spring 2021, I decided to approach students’ virtual attendance in the synchronous face-to-face classroom differently. I began the semester with the assumption that my students had no idea how to use Zoom for educational purposes and that I needed to teach them.

The Plan

<5>The second day of the first week of the semester was a Zoom-only class session for both of my face-to-face courses: Rhetoric & Writing, Chadron State College’s first-year composition class, and Elements of Literature, an introductory literature course. For each class, I blended a Zoom tutorial with a standard lesson to familiarize my students with learning in Zoom and help them feel prepared and empowered to use it whatever the semester might bring.

<6>My objective was to teach my students how to interact with myself, their peers, the course material, and the class as a whole in a virtual environment to ensure that they wouldn’t have to navigate and learn Zoom in isolation while ill with COVID-19, caring for family members, moving into isolation housing, or tackling any other crises that may arise. I wanted them to begin the semester with a sense of control and safety about their attendance. This lesson taught them how to contribute actively—and in various ways—to class while attending virtually rather than leaving them in a position where their only option would be to react to another overwhelmingly stressful emergency situation. Further, this lesson made my expectations clear to them. For instance, they knew that I would not require them to unmute their audio or turn on their cameras;(8) they also knew that I would always allow them to chat with me privately and that I would never reveal something from a private chat without their express permission. Finally, I indicated that I would ask them to signify responses to questions using the “Raise Hand,” “Reactions,” and “Chat” tools in Zoom. While my plans for these Zoom-only class sessions were quite simple (see full lesson plan in Appendix 1), they did something unexpected: they created multiple ways for students to engage in class discussion, which was no longer, strictly speaking, a verbal affair. This variation in discussion options resulted in a more collaborative learning environment.

Beginnings

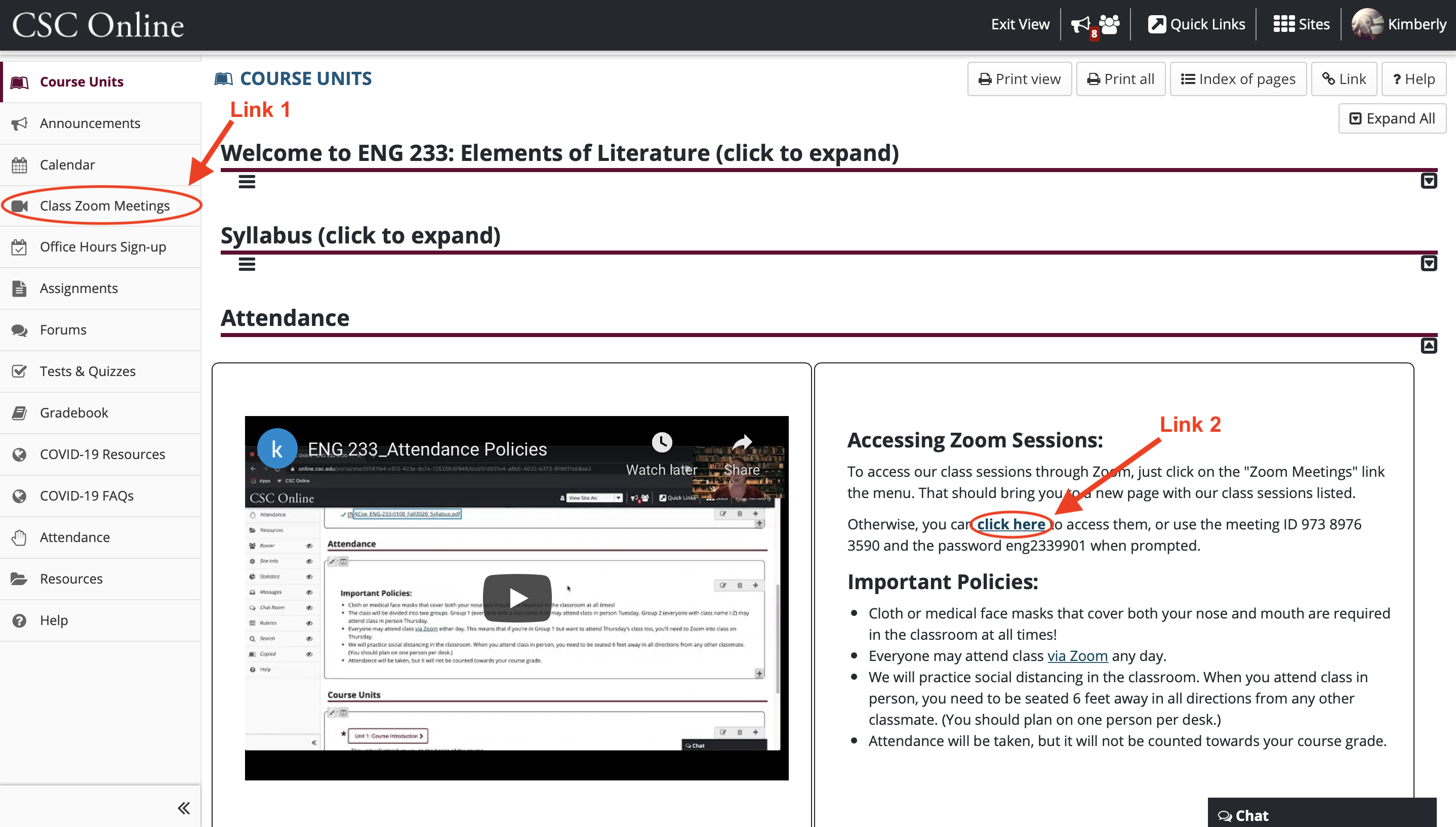

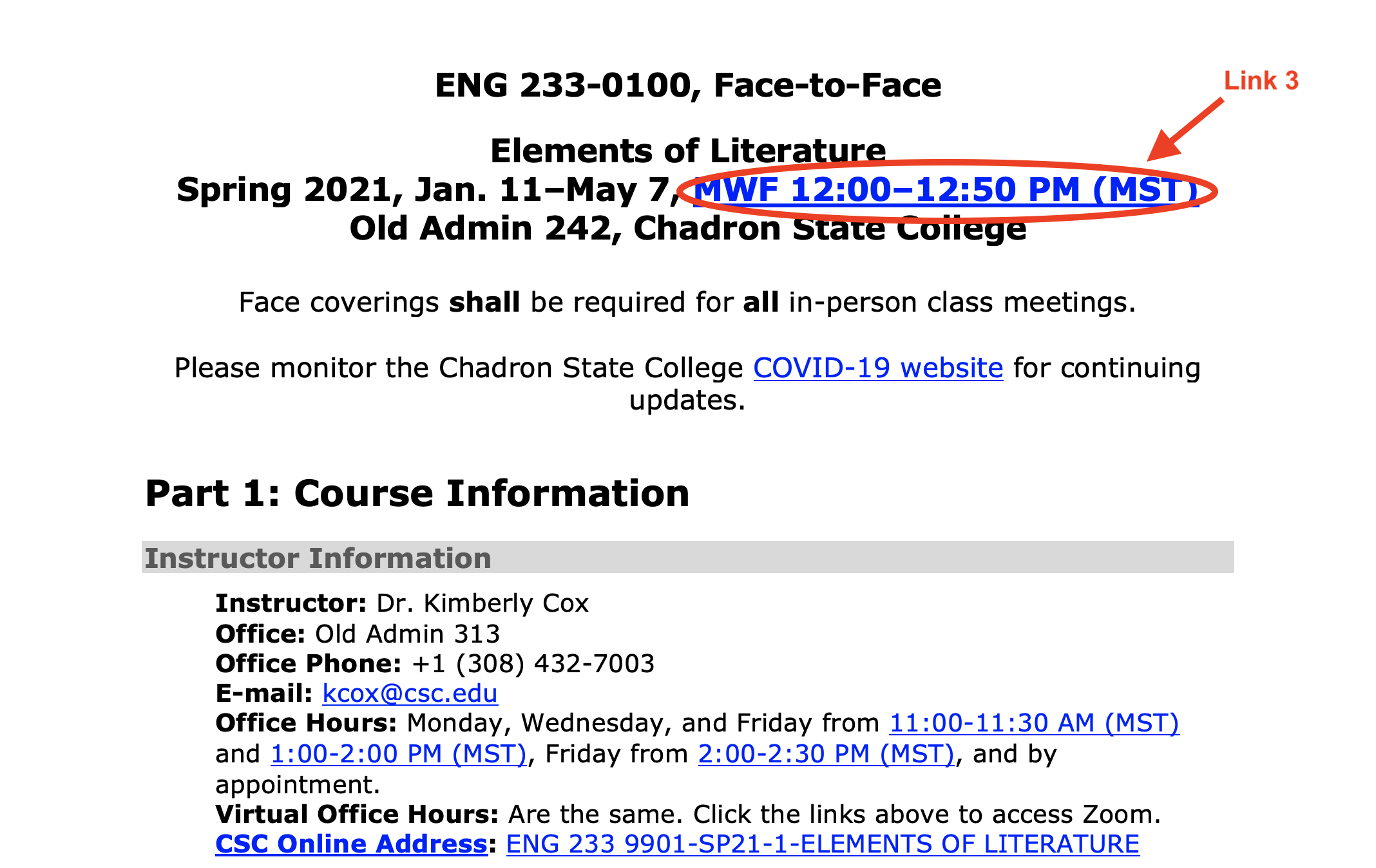

<7>My lesson began the first day of the semester when I projected our course site onto the screen and showed my students how to access the Zoom meetings for the class. Not only was there a tab in the menu called “Zoom Meetings” (see Fig. 1), but I created links on the course “Home Page” (see Fig. 1) and in the syllabus too (see Fig. 2).(9) I even created an instructional video (with a length of about thirty seconds) showing students where to find the links in our LMS and how to log in once they clicked on those links.(10) It turns out that this first step was crucial for my first-year students who had never before used Zoom (their high-schools used Google Meet), for my international students who were often overwhelmed by the sheer mass of text-based information they were given during the first few weeks of the semester, and for my non-traditional students who felt like they were starting school at a technological deficit.

Attendance

<8>On the second day of the semester, I sat in the classroom with three students who were nervous about Zoom and felt more comfortable joining the session from the same physical space as myself. Their laptops or cell phones were out, and we met the remaining seventeen students in Zoom.(11) I started the Zoom session by explaining that everyone would have the freedom throughout the semester to choose when (or whether) to turn on their video and/or audio since I would be recording class sessions for anyone unable to attend. Then, I explained that I’d be using Zoom’s chat feature to create an attendance record for those joining class through Zoom. After asking everyone to click on the “Chat” icon on the bottom of the screen, I posted a simple, low-stakes question not directly related to the course’s subject matter to build my students’ comfort sharing information with the class. “If you could be any non-human animal (actual or imagined), what would it be?” I asked my composition students; and “What’s your favorite genre of literature, music, movies, or television?” I asked my literature class. I posted my own answer (dragon and feminist fantasy/sci-fi) right after the question to model responding and make clear that I’d be participating with them.

<9>As people posted, I started commenting verbally on what they were typing into the chat that everyone could see. When I said things like “We have two who’ve said cow” and “I see some music genres,” some students voluntarily unmuted themselves to share why they posted these things or simply to comment on what they were noticing about the responses. This exercise also gave students who came in late the chance to get situated.(12) Beginning with an attendance question not directly related to the course functioned like an in-person ice breaker. It not only gave students a chance to practice using the chat function (and, unexpectedly, muting/unmuting their microphones), but it also allowed us to build a more informal, communal rapport since everyone who was present participated in the chat. In contrast to an in-person classroom where time sometimes prohibits everyone from sharing, it took three minutes for everyone to post their responses to my questions and for those who felt comfortable unmuting to join an impromptu, casual conversation about who wanted to be what animal or what genres people enjoy the most.

Discussion

<10>After taking attendance, I segued to teaching students how I use polls in Zoom as a means of generating a more topical class discussion. The host needs to set up polls in Zoom before the start of the session.(13) I created an anonymous poll in each class to ask a relatively simple question designed to get students thinking about how they relate to the course topics: for composition, “How do you feel about writing for school?”; and, for literature, “How often do you read for pleasure?” I gave students about a minute to respond after emphasizing that their answers were anonymous, a setting I used so that they could feel safe responding honestly. I also reiterated that there was no right or wrong answer. I shared the numeric results of each poll after everyone had responded. The results were split. In their responses to the writing question, about half of the class said either “Confident” or “Okay,” and half said “Nervous,” “Worried,” or “Scared.” In their responses to the reading question, about one third said they read “Daily” or “Weekly,” and the rest said “Monthly,” “Ever so often,” or “Never.” These polls gave students a chance to consider and share their affective experiences of reading and writing and, more importantly, to see that they weren’t alone in how they felt. This form of anonymity is more difficult to accomplish in an in-person class where such polls would require, at the very least, third-party tools. Further, the results offered me a sense of where my students were starting in regards to their experience and comfort with reading and writing.

<11>Prompting students to use Zoom’s “Raise Hand” button,(14) I invited those who responded with “Confident” and “Okay” (and then “Daily” and “Weekly” in my other class) to raise their virtual hands so no one was singled out. Then, students had the option to share why they chose what they did by keeping their hands raised; those who didn’t want to share found and clicked “Lower Hand” so I would know not to call on them. Everyone also had the option to post a response to the chat if they were shy (or were unable) to unmute but wanted to contribute to the discussion anyway. Some students feel more comfortable sharing textually, though most of the students who volunteered to share opted to do so verbally. I read out the responses posted to the main chat since they are visible to everyone.(15) All students lowered their virtual hands after our discussion ended. We then repeated the process with those who responded with “Nervous,” “Worried,” and “Scared” (or “Monthly,” “Ever so often,” and “Never” in the other). Surprisingly, most of them were excited to share, and many who lowered their hands initially raised them again after someone else shared about the aspects of writing or reading that they tended to struggle with or about how they’d been demoralized over the years.(16)

<12>Since these classes are about turning students into confident readers and writers, showing the students who were scared or who don’t read often that they still have something valuable to contribute was essential to the type of safe and open learning community I sought to cultivate with this lesson. This exercise offered students practice in responding to Zoom polls and raising and lowering their virtual hands, but it also functioned metacognitively. Students could anonymously acknowledge how they felt about writing or reading, discuss those feelings with others who have had similar experiences with these subjects, and share strategies for offsetting the challenges that they’ve faced. My role was to reinforce that reading and writing are not innate abilities that people either have or don’t. Rather, I stressed that these are sets of skills that could be learned by anyone willing to practice them. This exercise also afforded me the experience of reading what students posted to the chat as a part of class discussion. I volunteered names when comments had been posted to “Everyone” in the main chat and simply said “someone” when a student who chatted me privately gave me permission to share what they wrote. In those instances, I replied to the private chat explaining that it was an important observation and asking if they were comfortable if I shared it: “This is great! May I share it anonymously?”

Reacting

<13>The next stage introduced students to the reactions feature in Zoom so that they would know how to respond to questions that I ask and how to register their thoughts during class discussion or lecture. This exercise taught students that the logistics of communal virtual participation can be as haptic (the kinesthetic experience of clicking the buttons) and visual (appearance of emojis in the corner of their videos) as body language in the classroom. I created a PowerPoint with stock images focused on subjects that are communal and universal: food for my composition class and genres of fiction for my literature class. I chose these sets of images to set students at ease and ensure that everyone could react from a position of shared knowledge—though opinions varied greatly as I’ll explain.

<14>Before we began, I helped students locate their reactions. For some, it was as easy as clicking on the “Reactions” button. For others who had not yet updated their Zoom with the release of the January 2020 version, it was slightly more complicated and required clicking on the “Participants” button to bring up the side pane;(17) these students also didn’t have newer reactions like face-with-tears-of-joy emoji (😂), face-with-open-mouth emoji (😮), or the party-popper emoji (🎉). Then I clicked on “Screen Share,” I chose the PowerPoint, and we started.

<15>I put up the first slide and told everyone to react with “Yes” or “No.” Like a sports announcer, I narrated who was indicating what and then asked if anyone wanted to share the reason for their choices either verbally or in the chat. My narration helped my students become more aware and invested in how members of the class were responding, noting that large portions of the class often felt similarly. (My students have very strong feelings about mushrooms and romance novels!) Next, I asked students to use the “Slower” or “Faster” reactions. I used an image of pizza for my composition students and a dragon for my literature students. Instantly, some students unmuted themselves to ask how pizza or a dragon could be slower or faster. Others unmuted and said things like “How quickly do you want to eat it?” or “How fast should you cook it?” for pizza and “How fast should you run?” or “How fast does it fly?” for the dragon. Still others started using the reactions to respond to what their peers said. When they did, I’d narrate it: “Well, this person just used the face-with-tears-of-joy emoji (😂), so they seem to appreciate what you said!” or “Ooo, that person gave a thumbs up (👍), so they agree with you!” Students would often unmute to share why they reacted as they did, the software turning invisible as students began to focus on how the others responded and how those responses related to their own. After students were comfortable with “Yes”/“No” and “Slower”/“Faster,” I opened the reactions to any of the emojis and indicator words. It was fun,(18) but it also allowed me to use a mode of communication with which my students are familiar (emojis) in a way that cannot be replicated in the in-person classroom. Students also learned that they can effectively engage in and respond to virtual conversations even when they’re in their rooms with their microphones muted and their cameras turned off.

Working Together

<16>We then moved into group work in a remote space where I used breakout rooms to release students from my gaze and give them the opportunity to communicate with each other on their own terms and decide collectively what ideas to contribute to class discussion. I posted the question that each group would be working on into the main chat: for composition, “What’s one question you and your group members still have about the class after reading the syllabus? Choose one spokesperson to share.” For literature, “What are two important things to consider when choosing a novel to propose that we read?(19) Choose one spokesperson to share.” I then divided them randomly into breakout rooms. I joined each room in turn and re-pasted the instructions into the chat each time I entered a room; I learned on visiting Room 1 that, once students join their assigned breakout room, they no longer have access to the chat from the main Zoom session. I also answered any questions that students had. I gave groups five minutes with a two-minute reminder that I broadcasted to all the rooms by using the “Broadcast Message to All” feature in Zoom. This assignment was an essential component of the lesson for me because I wanted my students to know that their interests and concerns both can and would drive our discussions throughout the semester.

<17>As I joined the rooms in turn, it was clear that students’ comfort level speaking in breakout rooms varied. Some groups began discussing right away. A big topic was who was taking notes and who would be the spokesperson. Some groups were quieter and needed a little prompting. One group had a question. When I arrived in each room, I noticed that some students had turned on their cameras and, in some rooms, everyone was unmuted. In my estimation, my particular student body would benefit from a little more guidance to get conversation started.(20) In the future, I’d elect a group leader to initiate—not control—discussion for each group. My sense is that someone needs to speak first; once the silence is broken, students seem to feel more comfortable engaging verbally or posting to the chat. I’d also give a little more time for this exercise (I might break the whole tutorial into two days) and have each group test the new “Ask for help” feature in Zoom breakout rooms, which allows the participants to communicate with the host in the main session. I’d like students to practice calling on me if they have questions or need help getting started. Those concerns aside, each group had plenty to contribute to class discussion upon returning to the main session, suggesting that, whatever their initial reservations, they worked together to generate ideas and assess which ones to share with the class.

Reporting Out

<18>When all students returned to the main session, I asked the spokespeople to click the “Raise Hand” button to indicate who would report out for their groups and drive this part of the class discussion that focused on course content. I then shared my screen—the syllabus for composition and a blank Zoom whiteboard for literature—so students could use Zoom’s “Annotate” feature to identify or record the key information the spokespeople conveyed.(21) I paused a moment for everyone to locate their annotation tools. My students were very helpful here as those using apps (on cell phones or tablets) or a non-updated version of Zoom had interfaces that differed from mine. At least two students in each class unmuted themselves to give their peers instructions about where to find the “Annotation” toolbar, demonstrating investment in their peers’ success.(22) I gave students a few minutes to play with the annotation tools once they found them. The screen emulates the familiar classroom whiteboard but shows students that, in Zoom, they each hold a virtual “pen” and do not need to wait for me to invite them up to the board or hand them the dry-erase marker to contribute. It not only mirrors a space where shared written language emerges to support learning, but it offers students an even more direct line to contributing, decentering the instructor as transmitter of knowledge.

<19>Then, I called on the first spokesperson. For the question about the class or syllabus, I scrolled to the part of the syllabus that answered or commented on the question that each group expressed and asked students to circle, highlight, or draw an arrow pointing at what they thought the answer was. Not only did this exercise allow us to talk about how to use the syllabus, it kept students actively engaged while showing them that they were capable of finding answers to questions they might have in the future. For the question about what students should do when proposing novels for the class to read, I asked the students who weren’t speaking to type notes into the virtual whiteboard about what the spokespeople shared, guaranteeing that both those speaking and those listening had a way to engage. I learned that my students care about the amount of time it takes to read a novel and how relevant that novel is to their own lives. We agreed rather quickly that no one would recommend a novel over 250 pages to ensure that everyone—whatever their reading speed—would have time to read it. Equitable expectations emerged as important since more than half the class had shared that past negative experiences or unrealistic expectations made them hesitant to read. After each spokesperson reported their group’s answers, I’d have them use the “Lower Hand” button and call on the next person. In between, I’d offer opportunities for other students to ask questions and prompt them to use their reactions to ensure that we were building a class-wide knowledge base to which everyone contributed. The use of the annotation tools in Zoom was a little clunky—large font, overlaid text, and partial responses—but students erased what didn’t work and retyped to make their contributions clear.

Private Thoughts

<20>The final aspect of the lesson emphasized one-on-one communication, showing my students that they could feel comfortable interacting with me privately over chat (as I mentioned above, some had already figured out how to do this). I wanted them to know that I considered such communication an essential component of our learning community. I asked them all to click on the drop-down menu that lists participants in the chat and had them choose my name (which appears as “Kimberly Cox (she/hers)”; the pronouns have sparked productive conversation with individual students—as well as some colleagues—throughout the semester). I explained that private chat can be restricted or disabled by the host, so they may not always have this option available. Then, I invited everyone to chat with me and share whether they had any questions that they’d like me to answer at the start of the next class session and how they felt about Zoom after the day’s lesson. I posed these questions for this portion of the lesson to ensure that students could feel safe stating anything they didn’t understand without worrying about being judged by their peers.

<21>The responses that I received were all variations of the same thing, indicating that these sessions successfully accomplished my aim of empowering students as virtual learners and building a sense of classroom community. One student shared, “I did find this useful. I haven’t been able to really learn how to use zoom [sic] before so I really appreciate it. I don’t have any questions. Have a wonderful weekend!” Yet another explained, “Yes I feel as though this session was useful. It was enjoyable and I feel as though it was a good way to end the week. I do not have any remaining questions. Thank you!” Another reinforced my reasoning for running such a lesson in the first place, “I think this session was very helpful and useful not only in this class, but helped me understand zoom [sic] functions I did not know about which will help me in other classes! I do not have any other questions, thank you!” Every single student across both classes indicated that they found the Zoom tutorial within the lesson useful. Even the two students who said that they were still a little nervous about attending class via Zoom (both of whom, by Week Five of the semester, were opting to attend virtually with regularity) indicated that they found the lesson useful.

My Takeaways

<22>The results of this session were that my students became comfortable with the tools I would be asking them to use throughout the semester when they attended class virtually and that my students and myself began the process of building a classroom community where everyone could feel safe and respected contributing. Following this class session, my students raise their hands regularly to contribute to class discussion and use their reactions much more frequently this semester than last semester. I regularly get 👍/“No”s when I ask students whether they understand an activity or assignment, allowing me to identify and fill gaps like I would in a face-to-face classroom. Further, students who were initially very nervous about virtual attendance also choose to Zoom into class more frequently than I thought they would, suggesting that they feel comfortable with Zoom’s tools and attending class in any way that works for them.

<23>I am also more comfortable incorporating student Zoom reactions and the chat into classroom discussion. I now use the attendance question to focus discussion for the day; I ask my in-person students to write it down and share it out loud while my Zoom students post to the chat—I project the Zoom session onto the board in the classroom so students in the class can see the responses. My Zoom students have the option to unmute and share their responses. I opted to approach attendance this way to ensure that both my virtual and face-to-face students have equitable representation in class discussion, building a learning community that spans the virtual and in-person environments, even if that means narrating their reactions or reading their responses. Students still don’t usually use the annotation tools unless prompted (they are not the easiest to work with for a variety of reasons).(23) But students do frequently chat with me privately to ask questions or contribute to class discussion, and those who have something to say but don’t want (or are unable) to unmute regularly post their ideas or questions to the main chat. I also use breakout rooms frequently to ensure that students in Zoom have space to collect their thoughts, discuss them with others in real time, and report back to everyone in the face-to-face classroom.

<24>Unexpectedly, the emergency remote classroom has shown me that there are some real advantages to virtual instruction, particularly when that instruction focuses on empowering students as learners and collaborators within the classroom community. In fact, this lesson positioned me as a co-learner, modeling how I process the information, reactions, feelings, and ideas that my students share. Without discounting the value of the type of learning that happens within the face-to-face classroom, I was surprised by the fact that, throughout this lesson, every student “spoke”: they responded emotionally (emojis), textually (“Yes”/“No” and “Slower”/“Faster”), and verbally (after using “Raise Hand”); they posted to the chat, sharing thoughts both publicly and privately; they responded to polls; they collaborated with peers; and they wrote on the virtual whiteboard (using “Annotation”). Everyone contributed to class discussion multiple times in a variety of ways throughout the lesson, which doesn’t often happen in the face-to-face classroom. This approach created a strong sense of collaboration. Plus, the anonymous nature of many of these tools (e.g., polls, annotation, and private chat) created a safe way for students to share their comfort level with course material without feeling vulnerable or open to judgment. I came away pondering how a virtual classroom might create more equity in class discussion—and thus in building learning communities overall—for students who are shy, take more time to process material, are English language learners, or like having a variety of options for how they might respond. In-person classes privilege students who are comfortable and confident enough to speak up—a true lesson in Zoom.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to my students who were willing to engage in this atypical lesson on the second day of class and who have since shared their thoughts so openly. I’d also like to express my gratitude to Doreen Thierauf and Shannon Draucker, my co-editors of this special issue, without whom this piece wouldn’t have addressed the larger pedagogical implications of the lesson.